Science is in crisis. Funding infrastructures for both basic and applied research are being systematically decimated, while in places of great power, science’s influence on decision making is waning. Long-term and far-reaching studies are being shuttered, and thousands of scientists’ livelihoods are uncertain, to say nothing of the incalculable casualties resulting from the abrupt removal of life-saving medical and environmental interventions. Understandably, the scientific community is working hard to weather this storm and restore funding to whatever extent possible.

In times like these, it may be tempting to settle for the status quo of six months ago, wanting everything simply to go back to what it was (no doubt an improvement for science, compared to the present). But equally, such moments of crisis offer an opportunity to rebuild differently. As Arundhati Roy wrote about Covid-19 in April 2020, “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.” What could science look like, and what good could science bring, if we moved through the portal of the present moment into a different world?

At worst, science will play its part in accelerating us toward a tech-obsessed end-times-fascist future. At best, science will broaden its power as a positive force, serving the wellbeing of humans and nature alike. Imagining this latter vision in exquisite detail is essential, and we argue here that to first envision and then work towards the best version of science, we need to reckon honestly with science’s past and present.

Most crucially, we need to confront the commonplace claim that science is – or ought to be – objective and apolitical, uninfluenced by human culture, norms, or values. The current moment has rudely awakened many scientists to the fact that research is indeed political, and further makes clear that scientists’ attempts to distance themselves from politics will backfire. Denying the inherent entanglements of science and politics leaves scientists lacking the capacity and tools to mount effective defenses against bad-faith political attacks. This denial also allows science to go unquestioned when it undermines the needs and rights of marginalized beings and places.

As much as scientists might wish for science to be cleanly separable from politics, decades of research demonstrates that this has never been true, and never could be. The field of science studies examines the inherently human processes of science – who defines what science is, who gets to conduct scientific research, who pays for it, who benefits from it, who is harmed by it – and how these human dynamics shape scientific knowledge. Feminist science studies in particular documents how power and oppression shape scientific findings and applications, demonstrating that even “science at its most basic” is in fact inextricable from politics.

Some of the most compelling, and consequential, examples of such entanglement can be found in human and animal biology. Consider an analysis of 19th-century science on human race and sex from Sally Markowitz, which clearly reveals the influence of white supremacism on basic biology. Markowitz shows how 19th-century scientists not only asserted that human races are biological categories, but also that the so-called white race is evolutionarily superior.

To “prove” this politically-motivated claim, these scientists first decided that the degree of distinction between men’s and women’s bodies (or “sexual dimorphism”) was proof of evolutionary superiority, and then claimed, on the basis of selective measurements, that sexual dimorphism is supposedly greater in Europeans than in Africans. Women of African descent were thus mismeasured as both less female and less human than their white counterparts – rendering all people of African descent more “animal-like”. This 19th-century research has had far-reaching consequences, from justifying enslavement, to supporting eugenic sterilization practices well into the 20th century, to contemporary controversy around the “femaleness” of elite Black and brown female athletes, among other examples.

It may be tempting to relegate such blatant instances to the past, and claim that scientists have since corrected such mistakes. But in fact these ghosts continue to haunt us. In our new book, Feminism in the Wild, we – an evolutionary biologist and a science studies scholar – dive deep into how contemporary scientists describe and understand animal behavior, and find the dominant political perspectives of the last 200 years reflected back to us.

Scientific research on mating behavior in species ranging from fruit flies to primates is entangled with patriarchal expectations of masculinity and femininity. Scientists’ understanding of animals’ foraging behavior mirrors a capitalist theory of economics, based upon assumptions of scarcity and optimization, and expectations of individualism are pervasive throughout scientific research on how animals behave in groups.

Contemporary researchers express surprise, for instance, at elephants who alter their eating habits to accommodate a fellow herd member disabled by poachers, at ravens who alert one another to the presence of food in the dead of winter, or at female dolphins who begin lactating without having given birth in order to nurse calves whose mothers have died. Dominant evolutionary theories do not explain such instances of care on their own terms, but instead insist that these behaviors must ultimately be self-interested. Not coincidentally, these theories rooted in individualism only rose to dominance in the last 50 years or so, alongside the rise of neoliberalism.

Meanwhile, eugenic perspectives, rooted in racism, classism, and ableism, constrain how scientists understand sex, intelligence, performance and more, in humans and animals alike. For example, today’s scientists are still somewhat shocked by lizards who successfully navigate tree trunks and branches with missing limbs, as these agile lizards undermine the presumed correlation between an animal’s appearance, performance, and survival that’s captured in the phrase “survival of the fittest”.

Other scientists continue to argue that peahens (for instance) choose to mate with the most beautiful peacock, despite his expansive tail’s costly impediments, because beauty is a “favorable” trait even if it doesn’t promote survival. Such arguments about female mate choice are rooted in a theory developed decades ago by mathematician and evolutionary biologist Ronald A Fisher, a vocal advocate of “positive eugenics”, which means encouraging only people with “favorable” traits to reproduce.

Leonard Darwin (son of Charles Darwin), in his 1923 presidential address to the Eugenics Education Society, made this connection between Fisher’s theories and eugenics explicit, stating: “Wonderful results have been produced…by the action of sexual selection in all kinds of organisms…and if this be so, ought we not to enquire whether this same agency cannot be utilized in our efforts to improve the human race?” Leonard Darwin then went on to deliver an astoundingly modern-sounding description of sexual selection before considering its implications for effective eugenics propaganda.

We offer these examples (and many more, in our book), to show that scientific research on the evolution of animal behavior remains thoroughly and undeniably political. But the moral of our story is not that scientists must root out all politics and strive for pure neutrality. Rather, feminist science studies illustrates how science has always been shaped by politics, and always will be. It is therefore incumbent upon scientists to confront this reality rather than deny it.

Thankfully, for as long as science has been aligned with systems of oppression, there have been scientists and other scholars resisting this alignment, both explicitly and implicitly. In Feminism in the Wild, we detail the work of scientists developing new mathematical models about female mating behavior that discard old assumptions aligned with patriarchy and eugenics, instead demonstrating that it’s possible and even likely that female animals are not necessarily concerned with mating with the “best” males and that mate choice can be a more flexible and variable affair.

We discuss a rich history of theories about animals’ behavior in groups that take both individual and collective well-being seriously. And we explore alternatives rooted in queer, Indigenous, and Marxist standpoints, which counter the dominant view that animal behavior is all about maximizing survival and reproduction. Ultimately, we show that it is possible—and even desirable—to fold political analysis into scientific inquiry in a way that makes science more multifaceted and more honest, bringing us closer to the truth than a science which denies its politics ever could.

In this historical moment scientists must embrace, rather than avoid, the political underpinnings and implications of scientific inquiry. As Science’s editor-in-chief Holden Thorp put it in 2020, “science thrives when its advocates are shrewd politicians but suffers when its opponents are better at politics.” We agree, and further insist: scientists must reckon honestly and explicitly with the ways in which the knowledge they produce, and the processes by which they produce it, are already and unavoidably political. In doing so, scientists may lose the shallow authority they have harbored by pretending to be above the political fray. They will instead have to grapple with their own political perspectives constantly, as part of the scientific process—a rougher road, no doubt, but one that will lead us to a stronger science, both more empirically rigorous and more politically resilient.

Imagine if scientists seized this moment to remake science even while fighting for it. As MacArthur Genius and feminist science studies scholar Ruha Benjamin recently stated: imagination is “[not] an ephemeral afterthought that we have the luxury to dismiss or romanticize, but a resource, a battleground.” And, she continues: “most people are forced to live inside someone else’s imagination.” United in the goal of building a stronger science, we call upon scientists to put our imaginations to work differently, in ways that move us through this nightmare portal into a dreamier world, where justice is not cropped out of scientific endeavors but rather centered and celebrated.

-

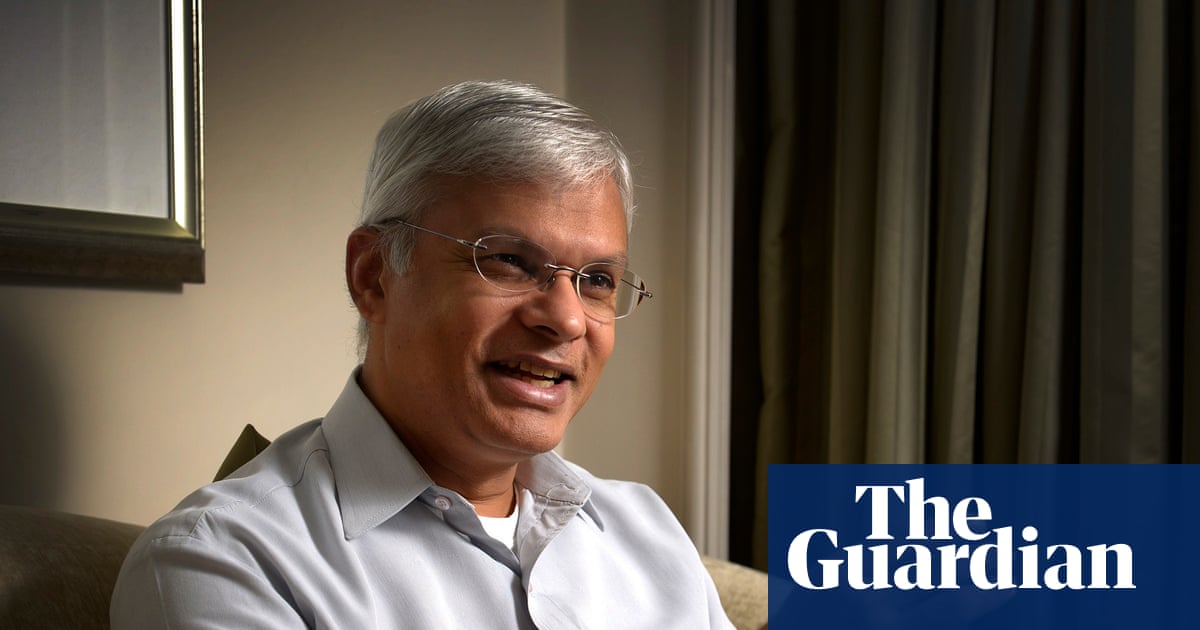

Ambika Kamath is trained as a behavioral ecologist and evolutionary biologist. She lives, works, and grows community in Oakland, California, on Ohlone land

-

Melina Packer is Assistant Professor of Race, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Wisconsin, La Crosse, on Ho-Chunk Nation land. She is the author of Toxic Sexual Politics: Economic Poisons and Endocrine Disruptions

.png) 2 months ago

23

2 months ago

23