Ricky* was one of the first to see his crewmate’s dead body. It was 2023 and he was six months into a stint at sea, working on a longline tuna boat in the Indian Ocean for $480 a month. The crew were mostly Indonesian, like Ricky, or Chinese, like the captain and owners of the boat.

In the days leading up to Ricky’s crewmate’s death, the 29-year-old Indonesian, referred to as YK, had been increasingly depressed onboard, repeatedly asking to be sent home. The captain had refused, says Ricky, who says he saw YK attack the captain.

“I came out of my room and saw he [YK] was fighting with the captain and other Chinese crew members, while the Indonesian crew tried to separate them.”

Ricky says he helped to break up the fight and then watched as YK, sporting a swollen eye and missing tooth, was locked in a storage room. For days, YK was kept inside, eating meals delivered by the boat’s cook who used what Ricky says was the only key, taken from the captain’s room. Around lunchtime on the third day, the cook arrived to find YK dead, says Ricky. Hearing the furore, Ricky ran to the storeroom.

“His corpse was already stiff, his body purple and swollen,” he says, pausing to demonstrate how YK’s body lay prone on the ground. “The strange thing was a rope around his neck which wasn’t attached to anything.”

The crew were divided, thinking YK’s death was either suicide or murder, says Ricky. It was ultimately reported as a fatal workplace accident and his family was awarded compensation of 200,000 rupiah (£9.60), according to a since-deleted notice and photos by a fisheries’ union, seen by the Guardian.

“Even though someone died, it seemed like nothing happened. We kept on schedule, no rest. One hour after we wrapped up the body, I was back at work,” says Ricky, who is not aware of any investigation into the circumstances of YK’s death.

YK’s body was stored in the boat’s freezer for another six months, the crew having to work around him every day. Ricky says they were told by the captain to stay silent during an inspection by authorities when they landed on one of the Pacific Islands. None of them could talk to anyone on shore. There was no wifi and only Chinese crew were allowed to use the one satellite phone, says Ricky.

“While I wrapped his body I had mixed feelings. I was sad, but also wondering how this guy ended up like this.”

Ricky is among the tens of thousands of Indonesian fishers who leave home – sometimes for years at a time – to work on foreign boats. Vast numbers are subjected to abuse, with vessels owned by companies from either China or Taiwan the worst offenders, according to a report published in 2023.

Deaths like YK’s are not uncommon, with more than 100,000 fishing-related deaths every year, according to estimates by the Pew Charitable Trusts, which says many are avoidable and most not officially recorded.

The issue was brought into the spotlight in March after a group of Indonesian fishers filed a US lawsuit against American seafood company Bumble Bee Foods – owned by Taiwanese tuna supply giant Fong Chun Formosa (FCF) – alleging it knew or should have known it was selling goods produced through exploitation and abuse of workers.

The lawsuit says the plaintiffs, from rural Indonesian villages, worked on boats that were part of Bumble Bee Food’s “trusted network” of suppliers. But once onboard they were “subjected to physical abuse and violence, deprived of adequate food, and denied medical care (and put back to work) even when seriously injured”. One man says he was repeatedly assaulted with a metal hook by his captain.

Greenpeace said the lawsuit was “potentially groundbreaking” in connecting US companies to offshore fishing abuses, putting commercial pressure on companies where advocacy has not worked. Bumble Bee Foods has told media it does not comment on pending litigation.

The case is by no means unique, but is representative of the abuse suffered by many others, according to fishers and human rights advocates the Guardian spoke to in Indonesia and who described their own “terrifying” experiences.

The problems start with recruitment, say workers and advocates. Legally, agents must register to directly recruit crew, but in practice there is an informal network of “calos”, or intermediaries, making commissions from referrals and recommendations.

“This information gap is used by agents and intermediaries to manipulate migrant fishers, so that they do not really know what to expect [in the job they are sent to], or if they’re being slaved or abused,” says Jeremia Humolong Prasetya of the Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative in Jakarta. “There are so many actors involved if it is not a direct transfer from home to ship.”

Once recruited, migrant fishers can wait for weeks or months before being sent to a vessel, with their passports and crucial documents withheld by recruiters. They are often made to stay in accommodation and later told they owe hundreds or thousands of dollars for the cost of their housing and recruitment. Salaries rarely exceed $500 (£390) a month. Ricky says he was charged $1,300 for unspecified recruitment and departure fees.

after newsletter promotion

The workers can also be forced to pay upfront “security deposits” of several months’ pay to guarantee they work through to the end of their contract, a fee which human rights advocates say adds pressure not to report abuse or quit.

The Bumble Bee case outlined similar accusations. It said the plaintiffs were ensnared by debt bondage, which meant they would owe money if they quit their jobs.

Once onboard and out at sea, there is little to prevent abuse, workers and advocates told the Guardian. Crew members are often transferred from boat to boat and there is no Indonesian government mechanism that keeps data on migrant fishers.

Akhmad, an Indonesian fisher in the Bumble Bee Food lawsuit, claimed: “One time, the rope holding the weighing gear broke and dropped a load of fish on me, cutting my leg open from thigh to shin.

“I was ordered to keep working … I could see the bone in my leg. I was left to clean and bandage my leg myself, without sterile medical supplies, and I kept bleeding for two weeks. It still hurts and probably always will.”

Ricky says he spent more than three years at sea onboard internationally owned vessels and says Indonesian workers were treated differently. “Chinese crew eat more and work less. Most Indonesians have to deal with the heavy tasks, even though they are in the same position,” says Ricky. Chinese crew were also paid more, he says, given about $900-1,200 a month.

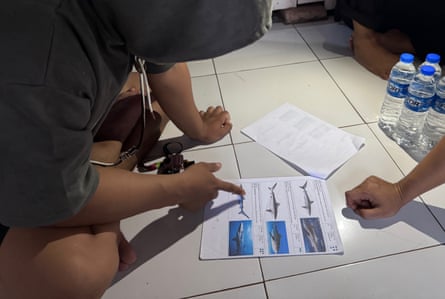

The workers who spoke to the Guardian say they also witnessed illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing on their boats. Dimas* showed the Guardian a video of crewmates catching a dolphin, and described the slaughter of a false killer whale so they could keep its teeth as souvenirs. Another worker, Edi*, says they caught “almost every type” of shark for finning, hiding the evidence in the back of the freezer.

When docked in foreign ports, workers are at the mercy of captains and owners who control their passports and access to funds. AJ* tells the Guardian of a “truly terrifying experience” after he and crewmates were ordered to risk their lives protecting the boat during typhoon Krathon in Taiwan last year, in direct defiance of city-wide orders to shelter.

Achmad Mudzakir, chair of the Indonesian Seafarers Gathering Forum advocacy group in Tawian, says: “These boats mattered more to the owners than our lives and safety.”

Taiwanese authorities have made some changes in recent years to improve protections for migrant fishers and sailors, including increasing the minimum wage to $550 a month and ordering direct payments that bypass recruitment agencies. There were also pledges to add CCTV and subsidise wifi on vessels, but there is no legal basis to compel shipowners to install it. Every fisher who spoke to the Guardian described wifi as a potential gamechanger for their working lives – allowing contact with home and an ability to report any mistreatment or other issues.

While Taiwan and South Korea have made some progress, say advocates, “China is absolutely the same, if not worse”. After recent allegations that its offshore fleets were illegally using forced labour of North Korean workers, Beijing said that all its fishing complies with international law.

Despite their own traumatic experiences, Ricky, Dimas and Edi all say they must return to working onboard trawlers. “My kids are growing, it’s hard to find a job here [in Indonesia],” says Dimas. Ricky says he is looking for work on a fleet from a country other than China or Taiwan.

All them hope, however, that by speaking out about their experiences, working conditions will improve. “We hope everyone can do advocacy for better conditions,” says Edi. “The boat owners treat us as slaves – no human touch, it’s just work, orders and obedience. We just want better conditions.”

* Names changed to protect identities

.png) 1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31