It took Joe Meanen about six seconds to hit the North Sea, after jumping 175ft (53 metres) off the burning wreckage of the Piper Alpha oil platform. The fall seemed to last for ever, during which time, he says, his first thought was: “What the fuck have I done?”

Piper Alpha stood about 120 miles off Aberdeen, on the north-east coast of Scotland. On 6 July 1988 it suffered multiple catastrophic explosions and collapsed, killing 167 of the 228 men on board, and a further two men from the rescue crew.

It was a Wednesday, and Meanen only had one more day of this two-week stint on the platform before flying home on Friday morning. He shared a room with three others, and they were all in high spirits knowing they were about to get some time off with their friends and families back on dry land. One of them, David Campbell, had just learned that he was going to be a father.

At about 9pm that evening, Meanen and his accommodation mates grabbed some Mars bars and settled in to the cinema with about 40 other crew members. Major construction and upgrades were under way on Piper Alpha at the time, yet because of the amount of oil the platform produced, it was kept operational throughout. Meanen recalls feeling uneasy about the effects of the works: “You could smell gas all over the platform. Sometimes, I even swear you could smell it inside the accommodation.”

At 10pm, a non-operational gas pump, which was missing a safety valve while it was being upgraded, was activated in error and then ignited, causing the first explosion. “The whole platform rocked back and forward,” says Meanen. “Part of the roof of the cinema collapsed, everything fell into pitch blackness – the lighting failed – so there was a panic in the cinema with people screaming to get back outside.”

Leaving the cinema, Meanen attempted to use the safety training he had received to prepare him for working offshore. But when he tried to reach his designated lifeboat, the magnitude of the explosion became clear. “The main control room was totally destroyed in the first explosion. Therefore no Tannoy [messages] went out. No alarms went off. Nobody really knew what to do.

“My first thought was to try to get to my lifeboat master station. But as I went over to the west side of the platform, there were people coming back from there, saying [there was] no chance you can get out that way as the smoke was too intense.” The fire was oil-based, he says, “which creates thick black, acrid smoke, so if you had gone outside in that without any breathing apparatus on you would have only lasted two or three minutes maximum before you were overcome by smoke inhalation”.

In the frenzy, Meanen became separated from his accommodation mates. He would not see two of them again, including Campbell – the father-to-be.

Meanen chose his next steps carefully. “Most people had gone up to the galley area, which was a designated safe area. It was fireproofed and it had a positive airflow [a kind of ventilation system to protect it from fumes], so it should have kept any smoke from coming in.”

It became clear, though, as he crouched there with about 100 men, avoiding smoke inhalation with a wet dish towel to his face, that he needed to keep moving. “You could hear other small explosions happening,” he says. “You could hear these groaning and yawning noises. It was the structure of the platform, which had been compromised and was starting to melt, starting to disintegrate – we didn’t realise that at the time. It was starting to twist and buckle and windows were breaking, letting more smoke in.”

Meanen and some others decided to go up to the helideck so they would be noticed quickly if any helicopters came to save them, but six men decided to stay in the galley. Meanen was one of the last to leave the area, shouting back: “‘Are you guys not coming with us?’ And they looked at each other and they said: ‘No, we’ve been told to stay, so we’re just going to stay.’ I said: ‘OK, good luck to you.’”

The bodies of the six men who stayed in the galley were recovered three months later, he says. The galley had fallen 475ft (145 metres) to the seabed after the entire structure of Piper Alpha collapsed.

As Meanen and other crew members climbed up to the helideck, through the thick black smoke, they found themselves faced with the harsh reality of the situation. “It was the first time we’d been outside properly since the first explosion,” he says. “And it became evident straight away that there was no chance of any helicopters even coming near the platform, never mind trying to land on it.”

They could see neighbouring oil platforms from this height, including the firefighting rig Tharos, which happened to be next to Piper Alpha that night, and started pumping water on to fires. “There were 14 of us and we were waving down at the Tharos. I’m sure they could see us.”

Then the second major explosion occurred, this time due to a gas pipe from a neighbouring oil platform, the Tartan, which burst from the heat radiating from Piper Alpha. “We didn’t actually know what had happened,” says Meanen, “but we knew it was something horrendous. Everybody just piled back on top of each other. As people got up they just ran away in all different directions, not another word was spoken.”

This was when Meanen realised his only chance of survival would be to jump from the platform into the North Sea to be saved by the rescue teams below.

Thinking quickly, he threw a lifejacket over the edge of the helideck and jumped, propelling himself as far as he could over the edge. He says the memory of his escape is hazy, but during his fall he sustained burns to his arms as they flailed in the air. He hadn’t touched the fireball on the way down, but the heat was so intense that even being near it was enough to leave scars.

After what felt like a lifetime, he plunged deep into the water. By following the light from the flames consuming Piper Alpha, he swam to the surface, where he found his lifejacket floating in the sea, and managed to use this and the roof of a lifeboat that had been blown from the rig to keep himself afloat.

He spotted the hull of the lifeboat and made a beeline for it. After pulling himself on board, floating away from Piper Alpha, he was finally able to see the ruins of the platform from which he had narrowly escaped. “I was looking back at the platform … trying to get a picture in my mind and thinking: if there’s anybody else left on that platform, they’re gone. But there were actually people who had got off after I had.” From the group of 14 that made it to the helideck, Meanen was one of five survivors.

A rescue craft found him and took him to a larger supply ship to get medical treatment at a neighbouring oil rig. He was then taken by helicopter to Aberdeen where he went straight to hospital for treatment. He never worked offshore again.

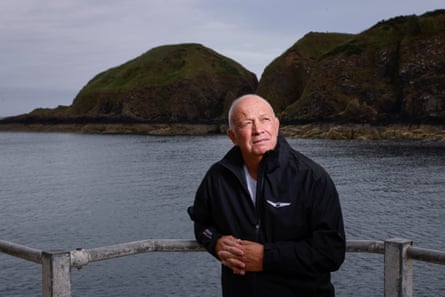

Meanen had started working on the rigs at 22, during the peak of the 80s North Sea oil boom. By the time of the accident he was 29 and working on Piper Alpha as a scaffolder. Originally from Glasgow, he moved to the north-eastern coastal town of Stonehaven when he started working on oil platforms.

Piper Alpha was operated by Occidental Petroleum (Caledonia) Ltd (OPCAL) and was the hub of a network of pipelines connecting it to nearby platforms and to shore. In 1988 the platform accounted for about 10% of North sea oil and gas production and was the world’s single largest oil and gas producer. At its peak it produced about 300,000 barrels of oil a day.

In the months after the Piper Alpha disaster, Meanen was in and out of hospital recovering from his burns, relaying his story and taking pictures of injuries for the inquiry into the disaster. He was also figuring out what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. The Public Inquiry into the Piper Alpha Disaster started in November 1988, and took 13 months to complete. The resulting report was critical of Opcal and found the company guilty of having inadequate maintenance and safety procedures. However, no criminal charges were brought against the company. The report also made 106 recommendations for changes to North Sea safety procedures. Occidental paid out $180m in settlements to survivors and families of the dead.

It wasn’t until Christmas that year, as Meanen sat in his living room, that the grief washed over him. “I was going to my mum’s later on for my Christmas dinner,” he says. “I just got up in the morning and I put on the telly, as you would, and I just sat there and all of a sudden I was consumed with grief.

“It was the first time it had really caught up with me and all I could think of was that this was the first Christmas that the mums and dads, the brothers and sisters, the wives and partners, and all the kids – this would be the first time they’d be without their dads or their brothers or their uncles, or their sons.”

Despite struggling, at first, to acknowledge his grief, Meanen has since adopted the belief that he should never shy away from talking about what he went through on Piper Alpha. “I have the opinion: nothing wrong with showing a bit of emotion and speaking how you feel … I’ve always been willing to speak and get it out there. I tend to look more on the positive side of things; how I was so lucky and fortunate.”

In the early 90s, Meanen and a few other survivors started a tradition of an annual meet-up in Edinburgh (the city to which they initially had to travel for their personal injury claims). “It’s great,” he says. “Sometimes Piper Alpha doesn’t even come up in our conversations, it’s just great to see them. If it ever does [crop up], we don’t have to explain anything to each other … If somebody has got any issues and they want to bring it up, we can speak about it and hopefully get it sorted out.”

After the disaster, Meanen had to wear pressure garments over the scarring on his hands and arms during summer to protect them. “I was wearing gloves during the summer time, these medical gloves,” he says. “Obviously people who didn’t know me [would give me] a few strange looks. For a couple of years or so I always bought long-sleeve T-shirts. Then I thought: ‘To hell with that, it wasn’t my fault.’”

He believes his physical scars played a role in helping him to recover mentally. “It’s obviously just my opinion,” he says, “that being physically injured and the scars you’ve got … give you evidence that you were there and you were involved and you’ve got the scars to show that. Whereas some people never got any physical scars, just the mental scars. I would think that’s a lot tougher for them.”

Meanen went on to marry and have two children, and own and run a pub, later working as a school bus driver. Now retired, he still speaks at oil companies, sharing his story and offering advice on safety offshore. It is important to him that the disaster isn’t forgotten, “hopefully to make things better,” he says, but also to honour “these people that had to sacrifice their lives”.

.png) 3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1