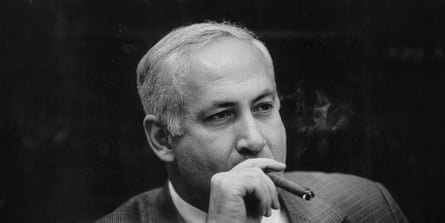

The Bibi Files, a new documentary, begins with its eponymous antihero, Benjamin Netanyahu, being read his rights by police interrogators. His oblong, jowled face is well known – Netanyahu has been Israel’s prime minister for a total of 17 years – but we are accustomed to seeing him in charge of events, behind a lectern haranguing his country and the world beyond. We have never seen him like this.

Late last year, videos of police questioning of Netanyahu, his family, his rich backers and his disillusioned aides were leaked to Alex Gibney, an Oscar-winning American documentary maker and one of the producers of The Bibi Files. The tapes were recorded between 2016 and 2018 and appear for the first time in The Bibi Files, which premiered at festivals in Toronto and New York but still cannot be viewed in Israel.

From the outset, we see Netanyahu literally backed into a corner, behind his desk, fending off a barrage of questions about lavish gifts which the police claim he received in return for favours, and about political favours that they claim were bestowed in return for flattering news coverage.

The leaked tapes themselves are compelling, but the director, Alexis Bloom, seeks to go further. The Bibi Files appears to draw a bright, bold, causal line between Netanyahu’s 2019 corruption indictment and the current state of the region. Netanyahu has repeatedly denied any wrongdoing, alleging he is the victim of a politically motivated witch-hunt orchestrated by liberal media and a biased justice system, and he formally pleaded not guilty in a trial which has now continued, off and on, since 2020. However, the film argues that the trial is part of the reason a desperate Netanyahu took his country and the surrounding region into the abyss. Netanyahu has said throughout the war that he is motivated by the need to reestablish Israel’s security.

Raviv Drucker, an Israeli television journalist and co–producer of The Bibi Files, has devoted much of his career to investigating allegations of corruption surrounding Netanyahu and his family. He says he always operated on the assumption that no one should be above the law, but now swears that, if he had known where Netanyahu would lead the country, he would rather the prime minister had never been indicted.

“If you had taken me through some kind of time tunnel and shown me where we are in 2024, I would have told you: ‘Just don’t start with these cases.’ I would throw all of them in the garbage, even though some of them started with my investigations,” Drucker tells me during a work visit to Japan. “This is the honest truth, because none of us would have imagined what Netanyahu would do.”

In a series of tableaux, we see the embattled politician confront his accusers. A uniformed officer opens proceedings by warning that anything Netanyahu says may be used in a court of law, and the prime minister reaches for a bottle of mineral water, as if looking for something to do that will come across as nonchalant. In the questioning that follows, Netanyahu will seek to project derision, bewilderment, boredom and anger. Yet sometimes, when the police reveal some unexpected piece of evidence appearing to corroborate their allegations, it is possible to catch a glint of terror in his eyes.

The setting for much of the drama is Netanyahu’s surprisingly modest office: an average-sized desk, a big map of the Middle East at his back, a shredder and an unplugged mobile radiator beside him. The prime minister knows full well his interrogation sessions are being filmed and may one day become public, but The Bibi Files is surely an outcome beyond his worst imagining.

Bloom, the director and co-producer, is a South African who has previously exposed some powerful and venal men. Her 2018 film Divide and Conquer looks at the rise and fall of the former Fox News boss and Trump-booster Roger Ailes.

Drucker, Netanyahu’s nemesis for many years, plays the role of chorus in The Bibi Files, chronicling the prime minister’s slide towards war and extremism. Netanyahu has tried to stop the film coming out with a series of injunctions aimed against Drucker, and his demeanour palpably tenses when the police drop the journalist’s name in one of their sessions with him.

Netanyahu tried to shrug off Drucker, as he has largely ignored Israeli media as a whole in recent years, but he could not dodge the police when they asked the same questions. “It’s pretty remarkable. It’s tens of hours of the most powerful men and women in Israel in the most extraordinary situation, where they are fighting for their lives, and it’s amazing to watch,” the journalist says.

We do not just see Netanyahu being quizzed, we also watch Israel’s super-rich squirm in the face of questions about the lavish gifts police claim that they presented to the prime minister and his wife, Sara. In the film, giving various accounts from former aides, it appears that the couple were not shy about soliciting such gifts – though the Netanyahus deny demanding presents from rich friends. In the particular case of a gift of jewellery worth tens of thousands of dollars, Sara tells the police in the film: “I did not personally ask for a ring and a necklace.” Her husband said he had no knowledge of it.

In return, it is alleged that favours were distributed, such as a US visa procured for a tycoon thanks to Netanyahu’s direct intervention with the then secretary of state, John Kerry. In another case, it is claimed that a government document was drafted and signed for a mogul, giving him access to hundreds of millions dollars in short-term funds which saved him from bankruptcy.

Netanyahu slaloms through the inquisition, dismissing some matters as trivial and private – simply gifts from close friends – his eyebrow raised at the impertinence of the questioner. Much of the time he claims simply not to remember.

Only occasionally does he seem to lose his temper and bang his desk, but when he does it comes across as just another act in the overall performance. By contrast, Sara Netanyahu’s rage seems genuine. She screams at the policemen that wherever her husband goes in the world, he is “treated like a king”. (The film was made before the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Netanyahu for war crimes in Gaza. Israel is appealing the warrants and Netanyahu denies the allegations, but meanwhile the prime minister’s travel options are limited.)

The couple’s son, Yair, who we learn in The Bibi Files may be groomed as a successor, is even more unbridled in his contempt for his interrogators than his parents, comparing them to the Gestapo. The inflammatory rhetoric he has spread online embodies the end-point of his father’s political journey from centre-right dealmaker to the head of the most extreme government in Israeli history. It includes previously fringe figures such as Itamar Ben-Gvir, who has a past conviction for inciting racial hatred, and Bezalel Smotrich, a former political activist who was arrested in 2005 in possession of 700 litres of petrol allegedly intended for use in blowing up a motorway running through Tel Aviv – though he was released after three weeks without charge, and denied the allegation. They are now ministers for national security and finance respectively.

Drucker argues that Netanyahu’s sharp turn to the right has its origins in his corruption indictment. The prime minister stunned people by refusing to resign, and when the indictment narrowed the field of Israeli parties willing to form a coalition government with him he turned in 2022 to the only alternative that would keep him in power.

“This is the only reason that he established the most far-right coalition that was ever established in the history of Israel,” Drucker said. “Ben-Gvir and Smotrich are two lunatics from the far right. They represented a tiny fraction of the population.”

He argues Netanyahu’s determination to avoid being tried led him to try to dilute the power of Israel’s supreme court, which may one day sit in judgement over him, by abolishing the court’s power to overrule government decisions. That attempt split the country and brought the biggest protests in Israeli history on to the streets last year, though the supreme court ultimately struck down the law at the heart of this judicial overhaul project.

Following the far-right agenda of his coalition partners, meanwhile, entailed focusing the military’s effort in the West Bank in support of Israeli settlers, moving units and weaponry away from the south, where Hamas struck in October last year, killing 1,200 Israelis and taking 250 hostage. “Hamas of course has always wanted to destroy us. It’s not because of Bibi,” Drucker stresses. “But they recognised a great opportunity and they took advantage of it.”

Once the Gaza war had been started by Hamas, Netanyahu has had every reason to keep it going, even after almost every Hamas leader and military commander has been killed, among an estimated 44,000 Palestinians in total.

His hard-right partners could tolerate a truce in Lebanon but would walk out of the coalition if there is a hostage deal with Hamas involving a prisoner exchange and a ceasefire. That would trigger new elections – which opinion polls suggest Netanyahu would lose. He would be stripped of the executive power he has been using to stay out of court and potentially out of jail.

“That would be a disaster for him,” Drucker said. “He will do everything he needs to keep on going with the war, and he will keep on going until there is a situation when it endangers his political survival. And then he will stop the war.”

Throughout the Gaza war, Netanyahu has insisted that it was Hamas who were the main obstacles to a ceasefire deal, but at the same time insisted that he prosecute the conflict until “total victory”, the complete destruction of Hamas.

Even if Netanyahu ends up being convicted, Drucker doubts he will ever spend time in jail, but will rather keep his appeals going until his advancing age leads him to be spared from incarceration.

But after all his years investigating Netanyahu, culminating in The Bibi Files, Drucker finds that he cares much less about the prime minister’s ultimate fate than he used to. “Two years ago, it was the whole world for us: the rule of law, everybody being equal, even the prime minister,” he says. “But now we are stuck in such a terrible mess in Israel. Our whole foundation is rocking every day beneath our feet. Now all we want is to live without the sirens and having to take our kids to air raid shelters.”

.png) 1 month ago

19

1 month ago

19