‘I don’t think I’ve ever worked so hard,” says Helen Marten. “I’ve literally not taken a day off for four months.” The artist is talking about 30 Blizzards, a two-hour opera for which she was commissioned, by Art Basel Paris and the fashion brand Miu Miu, to write the libretto and design the staging. Featuring 30 main characters – named things like The Mother, The Baker, The Asphalt, The Forest – and a chorus collectively called Dust, the whole piece moves from “deepest night through all of these iterations of the day – dawn, afternoon, then back to deepest night”. It will take place in a space 200 metres long, with the audience able to mingle with the performers throughout.

It sounds exhausting, but Marten, by her own admission, is “a total workaholic”. During our lengthy chat, she repeatedly darts off to leaf through a file, pull up a video, glance through a book, or play a voice memo – talking all the while.

The artist, seated in her London studio, pulls up images of the multiheight set she has designed for the opera and plays rough edits of the five new video works has written and shot. In one, we hear a girl say: “Today, I hopped around my room on one foot and then backwards on the other foot. Do you believe in ghosts, Lupo?” Even in this unfinished state, being shown the work feels a lot like being made tiny and placed – like a figure in a doll’s house – into a Helen Marten installation.

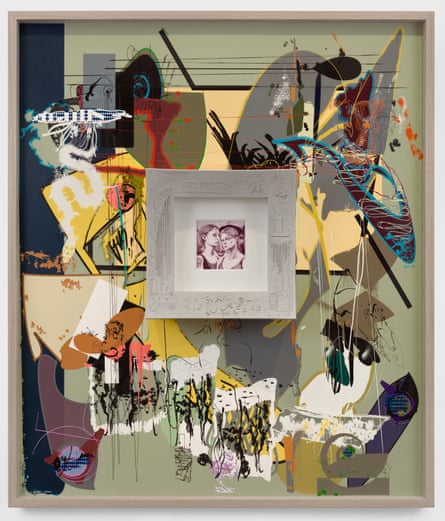

Marten is also preparing for a solo exhibition at Sadie Coles HQ, called Treatise of a Coat. This is the first time Marten has shown a large body of her wall-based works. Like nesting dolls, these comprise coloured-pencil drawings, mounted inside highly sculptural protruding frames, themselves mounted on elaborate, multilayered screen prints and framed again. She says the drawings are “very focused, myopic” depictions of moist things: people eating snails, animals licking cakes, lots of mouths. “They’re not surreal, but there is an oddness to them.”

Marten, now 39, won the Turner prize when she was 31, making her the second youngest to win the award after Damien Hirst, who was 30. She had been picked for a collection of mesmerising sculptural works, some of which she’d shown the year before at the Venice Biennale. Critics greeted Marten’s victory, not to mention her pioneering political gesture to share with her fellow nominees the £25,000 Turner winnings and the £30,000 from the Hepworth prize she’d won weeks earlier, with both rapture and bewilderment. “Rarely have I been so struck,” wrote one. “The meaning of the work is only known to her,” mused another.

Marten felt, as she puts it, “fragmented”. “It was a really manic year,” she says. By the end of it, she felt “so tired and sad from pushing work off into the world, allowing it to go and stand up on its own – and then be completely misinterpreted as ‘an assemblage of found objects’. I labour fiercely on these works. Every move when I make a sculpture, every part of it, means something explicit to me. There’s almost no found object in my work ever. If it looks like a found object, a deliberate mode of approximation and deception has gone into making it look so defiantly real.”

These days, she says, she barely thinks about the Turner. It certainly didn’t stop her making work. “If anything,” she says, “it made me more ferocious.”

In 2019, Marten decided to write a novel. Being free from the constraints of “gravity, production, shipping, physical making, everything, all of it,” she says, “was just so much fun.” Titled The Boiled in Between, it runs to 321 pages of dense, crisp, utterly confounding prose, and was published in 2020, during lockdown.

“This is my proudest moment,” she says, pointing to the blurbs on the back. She cold-called the writers she admired the most. The Nobel prize-winning Austrian author Elfriede Jelinek wrote back: “A cosmos emerges in the work of Helen Marten, we know it and we don’t.” So did American author Helen DeWitt, who said reading Marten’s work produced the same shock Alexander Calder said he had experienced when visiting Mondrian’s studio in 1930: “Like the baby being slapped to make its lungs start working.”

Coming back to making after that writing phase was a challenge. “I felt so fraudulent in the studio,” Marten says. She had to relearn that “tactile possessiveness over material” that has always underpinned what she does.

after newsletter promotion

Marten grew up with her twin sister in Macclesfield. While her sibling is a naturally numerical person, for her it was always about language. “I was definitely a pale, quiet, strange child,” she says. “I would always collect little bits and pieces and put them into funny taxonomies. I had a toothbrush collection that I, at one point, strung up like little bunting around my bedroom. I had collections of so many strange things. I still do.”

She pulls down a portfolio folder from a top shelf, which is bursting with paper bags from shops across Europe. She began to collect them, in earnest, about five years ago, variously pilfering them from fruit stalls or receiving them as donations from like-minded enthusiasts. “The Dutch ones are amazing,” she says. “The Netherlands is really good at paper packaging. The French ones are also very good.”

We’ve been speaking for two hours and, throughout, Marten has remained fully focused on the interview, her gaze and tone never wavering. In the background, her desktop email has been pinging incessantly but she’s not complaining: “I absolutely love everything I am allowed to do. I feel so lucky to have the access and the support to do it and to, like, know what I love.”

.png) 3 hours ago

4

3 hours ago

4