A family of six pulls up to the Be Prepared Expo in Farmington, Utah. They are concerned about supply-chain failure, sure of the fact that the Covid-19 pandemic was only a taste of what’s to come.

They want to buy seeds for their garden so they can grow food to preserve and stash in the basement. The kids pet the puppies at breeder booths selling guard dogs, the father exchanges opinions about the best weapons to cache, and the mother gathers pamphlets about hoarding gold and the crises of the international economy.

Quietly between booths, old copies of the novel The Turner Diaries (1978) by the white nationalist William Pierce are passed from hand to hand, while speakers give lectures about water filtration systems and the moral imperative of self-reliance.

As Chris Turpin, the CEO of the Be Prepared Expo, said in an interview: “Preparedness helps you from eating your neighbour.”

One way to forestall eating your neighbour is to stock up on supplies at Costco. In any US suburb, a family of four rolls a cart through the cavernous warehouse, placing a ReadyWise food bucket of emergency rations next to a box of muffins and packs of socks. They return to an unremarkable home in a neighbourhood that could be anywhere.

There are no trap doors, underground bunkers, or stashes of gold. But there is a gun safe in the garage, long-lasting emergency provisions on a designated shelf in the pantry, and Ring cameras installed inside and outside the house. The kids have their own LifeWater straws to filter freshwater, and their parents watch the news carefully for signs of growing instability in global affairs, of interrupted trade relations, of the return of Jesus Christ.

Welcome to the diverse world of prepping.

There are more than 20 million Americans who engage in prepping, while the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema) determined in a 2023 survey of Americans that 51% are “prepared for a disaster”.

Why do people doomsday prep? We approach this question in our book Be Prepared: Doomsday Prepping in the United States (2024) without speculating about their psychology. As political scientists, we are not equipped to assess what goes on in people’s heads, much less whether they sincerely or genuinely believe these things. We have no idea if preppers truly believe the end is near, are merely hedging their bets, or if it helps them cope with some underlying trauma.

We also have no idea, of course, if “the end” is actually near. Rather, we ask, is prepping a fringe activity gaining mainstream traction, or is it as American as apple pie?

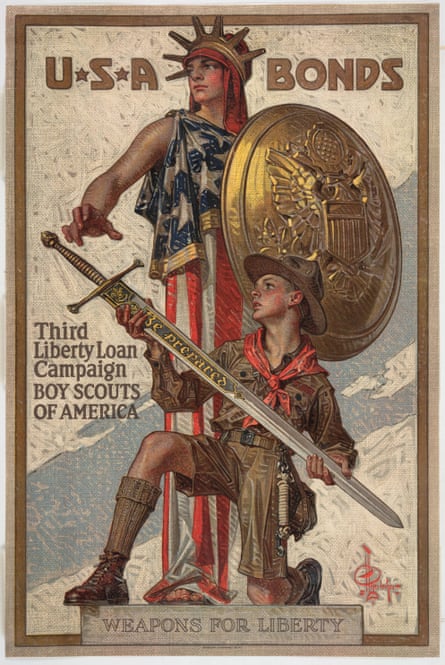

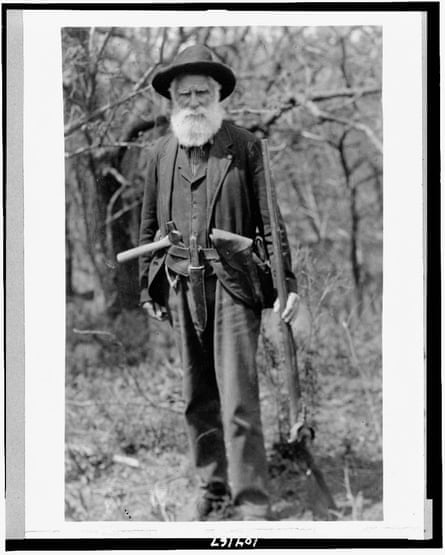

Prepping has been part of the American ethos well before neoliberalism and even before our contemporary industrial supply chains. Americans have been urged and trained to prep as children in various scouting organisations, as homesteaders given a plot of land by the federal government in the colonial project of “taming” the west, and as steady, patriotic citizens prepared to survive nuclear attack to keep the US alive in their bunkers.

Even after the bunker market floundered in the 1960s, the bunker exceeded its limits as an object and has transformed into a subjectivity, a way of life. This is the “bunkerised” citizen.

Bunkerisation explains the phenomenon of prepping in the US. The concept allows us to recast prepping as a matter of institutional development, as well as a process of how everyday life in a neoliberal order is oriented toward the logic of the bunker.

This does not mean that Americans are in a mad dash, as they were in the 1950s and 1960s, to construct fallout shelters during the cold war in the case of nuclear conflagration. Rather, the logic of the bunker shapes how Americans relate to each other, the state, and how they construct their domestic lives, as a matter of individual isolation, preparation and savvy consumption.

As such, bunkerisation posits that far from being at the fringes of US society, prepping is at the core of an American mythology of yeoman frontierspeople, from the Boy Scouts of America to the contemporary homestead movement. Bunkerisation as a process also plugs into the broader US phenomenon of mass consumption as Americans are asked to purchase their way to safety (to borrow a phrase from the sociologist Andrew Szasz).

Bunkerisation is not an indictment of contemporary US culture or a meditation on the moral failings of irrational consumers. It is an instance of consumer society, but one that is fully within the US mainstream and which makes safety a private family matter. This orientation paradoxically reflects a patriotic commitment to being an American by isolating oneself from other Americans in times of crisis.

Homesteaders in the American Redoubt of northern Idaho (a proposed homeland for white Christians), suburban preppers in Utah and wealthy venture capitalists with bugout-ready helicopters all exist within the bunkerised world, together. Multiple psychological orientations, worldviews and political ideologies find common motivation in bunkerisation.

The US has always urged its citizens towards self-defence and self-sufficiency, and to be in a permanent state of alert for ideological and material threats not just to the individual, but to the American way of life that the individual embodies. The Boy Scouts of America disciplines the self to “be prepared”. The American handicraft movement popularised in the late 1800s and early 1900s responded to the loss of art, craft and self-sufficiency posed by dependence on industrial supply chains to provide for our needs. The atomic era urged citizens to mobilise their fear of communism and Soviet attack into preparation for the worst-case scenario, not because each individual’s life is so important, but because this would warn the communists that Americans were prepared to die as Americans, before succumbing to communism.

Situating prepping at the centre of US life through the process of bunkerisation allows us to shift from how or why Americans prep to analysing how we ended up producing the prepping American who shapes everyday life.

For the average prepping American, simply stockpiling to meet Fema recommendations for survival in the absence of state support is not being a doomsday prepper but simply being a reasonable, prepared citizen.

Being an American often means understanding that, during instances of calamity, we all must do what we can to protect ourselves and our families. The tension in this construction of Americanness is both one of magnitude and responsibility. That is, if the power goes out because of a power-grid failure and one does not have the requisite amount of water on hand or did not buy a generator, that might prompt a discussion of individual responsibility, or at least about making sure people have the resources to make it to the other side of catastrophe.

That tidy, if contained, discussion, however, does not take into account the magnitude of the crisis. What happens if superstorms cause widespread infrastructure damage and the government response is uncoordinated, insufficient, or otherwise ineffective?

This is squarely a social question about political will and collective action to confront shared threats together. Yet bunkerisation encourages us to see the prepping American as a vector of individual and consumer responsibility, and not a question of the social scale of meeting shared threats. Instead, the prepared American is asked to focus only on security practices through consumption at price points that their means allow.

Towards those ends, more than 10 million Americans have Ring camera surveillance systems, in addition to the number of Americans who have other brands of security systems.

Nanny cams, firearms accumulation, the proliferation of gated communities and private security services are all manifestations of a bunkerised society. More than preparing for anticipated episodes of disruption or violence, a bunkerised society maintains a permanent state of readiness, not as a feature of a subcultural association, like doomsday preppers or homesteaders, but as a condition of living in the hollowed-out shell of a state that does not take infrastructural stability and basic need satisfaction as a right, but as a good one must supply for oneself through consumer choices on the market.

Of course, Fema’s failures to provide timely and critical assistance in the wake of disasters like hurricanes Helene and Milton help fuel prepping activity, and even get absorbed into conspiracy theories about state negligence at best and state malice at worst.

Looking at bunkerisation in this way helps us get past treating preparing as a matter of smart American consumers building a cache of goods to make it through troubled times, and it helps us avoid merely gawking at unfamiliar lifestyles and motivations.

It asks us to take seriously the shared threats that citizens in a political society face and to treat those threats as collective action problems instead of reasons to close the bunker hatch. This is no small task, because the institutional and ideological dimensions that we flesh out have produced a prepping American who treats threats as personal responsibility, which is reinforced by a neoliberal regime of degraded state involvement.

This attitude is perfectly encapsulated in the 1958 annual report of the Federal Civil Defense Administration – the forerunner to what eventually would become Fema:

Common prudence requires that the Federal Government take steps to assist each American to prepare himself [sic] – as he would through insurance – against any disaster to meet a possible – although unwanted – eventuality … When a free America was being built by our forebears, every log cabin and every dwelling had a dual purpose – namely, a home and a fortress. Today the citizen should be called upon to make the same contribution as our forebears – not for building a free America, but for sustaining a free America.

The myth of the yeoman frontiersperson taking individual responsibility for any catastrophe is baked into the bunkerised life of the prepping American. Overcoming that is not simply a matter of attitude, but a political project of reinvigorating the collective dimensions of public life.

.png) 1 month ago

10

1 month ago

10