With age comes disease. Cancer and Alzheimer’s dementia are among the commonest and most feared health conditions – particularly in countries with ageing populations such as the UK. Several decades ago, researchers at a psychiatric centre in New York observed a curious relationship between these two diseases. At autopsy, they found an inverse relation between cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

In one of the first epidemiological studies on the topic Jane Driver of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts in the US followed 1,278 participants aged 65 and older for a mean of 10 years. Published in 2012, the results showed that cancer survivors had a 33% decreased risk of subsequently developing Alzheimer’s disease compared with people without a history of cancer.

As intriguing as the finding was, the scientific community urged caution and pointed out potential pitfalls in dealing with age-related diseases. One of them concerned a so-called survival-bias: perhaps people with a history of cancer simply do not live long enough to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Since then, scientists around the world have analysed the relationship between cancer and Alzheimer’s disease in more detail and built an increasingly compelling case. In the largest study to date, published in July this year, researchers at Imperial College London provide convincing evidence of a lower incidence of dementia following a cancer diagnosis. They looked at the NHS health data of more than three million people aged 60 and over and followed them for a mean period of 9.3 years, taking extra care to correct for potential biases. Their results show that cancer survivors have a 25% lower risk of developing age-related dementia compared with people without a history of cancer. The inverse association was observed for the most common types of cancers such as prostate, colon, lung and breast.

“The relationship between cancer and Alzheimer’s disease is very intriguing and it’s persistent,” says Erin Abner, a professor at the University of Kentucky. “A lot of people questioned the results and tried hard to find other explanations for the inverse association, but it just keeps showing up, even after taking confounding factors into account.”

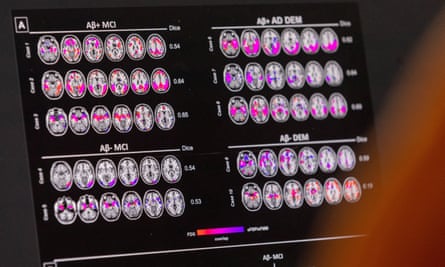

Two years ago, Abner published clinical evidence for the inverse association. Unlike previous epidemiological studies, she looked at brain autopsies of patients at the University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. “We found a pretty consistent association between someone having had cancer and having lower levels of amyloid pathology in their brain, which is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease,” she says.

In her study the inverse association was seen only with Alzheimer’s disease and not with dementia in general. In contrast, many of the previous epidemiological studies did not differentiate between Alzheimer’s and other age-related dementias. The majority of elderly patients with dementia, however, have Alzheimer’s.

But that is not the whole story; there is another twist to the inverse relationship. Not only do those with a history of cancer have a decreased risk of dementia, but those with Alzheimer’s disease are less likely to develop cancer. In her 2012 study Jane Driver reported that the inverse relation goes in both directions, a finding that was replicated in northern Italy looking at more than one million residents, and more recently in South Korea. According to this study, patients with Alzheimer’s disease show a 37% lower likelihood of developing overall malignancy compared to those without dementia. Again, the finding was met with scepticism. Perhaps, critics argued, people with dementia were less likely to be screened for cancer given the potentially limited benefit of therapies.

“The results have been replicated again and again, and most experts in the field now believe the inverse relation appears to be real,” says Elio Riboli who led the study at Imperial College London that also confirmed the bidirectionality. “The next step is to understand the biology behind this phenomenon.”

Some researchers have suggested that cancer treatment itself may be having an effect on dementia risk. In recent years, inflammation has emerged as a central process in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease, so it is possible that chemotherapy may be protecting neurons by suppressing inflammation.

But for Elio Riboli, that is not the whole story. The fact that the inverse relationship is bidirectional suggests there may be underlying biological mechanisms that influence the two groups of diseases in opposite directions. The researchers at Imperial College performed genetic analyses. “Looking at hundreds of genes, we identified a genetic profile that predicts an increased risk of cancer and we found that this profile is tied to a lower risk of dementia.”

after newsletter promotion

According to Riboli, the specific genetic factors may be involved in tissue regeneration. “Growth factors are a large family of molecules that regulate tissue renewal and growth. They are generally associated with better cardiovascular health,” he says. “Having a genetic makeup that favours replication allows for better renewal of tissues and arteries, but may also slightly increase the risk of some cancers.”

Surprising findings can open new lines of research, says Riboli. For instance, it has long been known that people with diabetes have an increased risk of developing cancer, with one notable exception: men with diabetes have a 10-20% reduced risk of developing prostate cancer. “Why does being diabetic come with a reduced risk of prostate cancer, a cancer for which we are desperately trying to understand the risk factors?” asks Riboli. Similarly, research into the inverse association between cancer and dementia may shed light on new molecular pathways that contribute to, or protect people from, the development of dementia. “You open a window and suddenly you see a new horizon,” he says.

Cancer is linked to uncontrolled cell growth, whereas dementia is tied to excessive neuronal death. Mikyoung Park of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology in Seoul, South Korea, recently published a review of molecular mechanisms that operate inversely in cancer and neurodegeneration – some leading to enhanced resistance to cell death and others to a higher risk of cell death. Dysfunctional mitochondria, the cellular power plants, might provide a crucial link between cancer and neurodegeneration, a hypothesis put forward a decade ago by Jane Driver and Lloyd Demetrius, based on mathematical arguments.

Unravelling the inverse association between cancer and neurodegenerative diseases may ultimately help treat or prevent these common conditions. But many questions remain unanswered. “Both cancer and dementia are actually a bunch of different diseases,” says Erin Abner. “We don’t have the granularity of data to draw strong conclusions about any one type of disease.” Additionally, there is a long latency period between the development of pathology and the start of symptoms, both in cancer and Alzheimer’s, raising questions around the timing of this inverse relation.

These enigmatic findings have no practical relevance for the time being. “But even now, it may be just a little piece of comfort for cancer survivors, that something is going to be a bit easier for them down the road,” says Abner.

.png) 1 month ago

15

1 month ago

15