Poised on a steel cable a quarter of a mile above Manhattan, a weather-beaten man in work dungarees reaches up to tighten a bolt. Below, though you hardly dare to look down, lies the Hudson River, the sprawling cityscape of New York and the US itself, rolling out on to the far horizon. If you fell from this rarefied spot, it would take about 11 seconds to hit the ground.

Captured by photographer Lewis Hine, The Sky Boy, as the image became known, encapsulated the daring and vigour of the men who built the Empire State Building, then the world’s tallest structure at 102 storeys and 1,250ft (381m) high. Like astronauts, they were going to places no man had gone before, testing the limits of human endurance, giving physical form to ideals of American puissance, “a land which reached for the sky with its feet on the ground”, according to John Jakob Raskob, then one of the country’s richest men, who helped bankroll the building.

Known for his empathic studies of workers, artisans and immigrants, Hine was hired to document the development of the Empire State Building during its breakneck 13-month construction period from 1930-31. Along with formal portraits of individual workers, he recorded men animatedly performing their jobs: drilling foundations, wrestling with pipes and cables, laying bricks and navigating precipitous steel beams as the colossal skyscraper took shape above Manhattan.

Today, visitors to the Empire State can take selfies with bronze sculptures of old-timey construction fellows, wreathed in a confected soundscape of “ironworkers and masons shouting over the din of machinery, moving steel beams into position, and tossing hot rivets into place”. This genuinely heroic feat of construction has long been commodified into a yet another visitor experience.

History valorises the ambitious, affluent men who commissioned the Empire State, including Alfred Smith, a former governor of New York and Democratic presidential candidate. It also valorises its architects, Messrs Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, who alighted on a distinctive art deco style, with prefabricated parts designed to be duplicated accurately in quantity and then brought to site and put together in a similar manner to a car assembly line.

Yet the men who assembled those parts – 3,000 workers toiled on site each day – are largely unknown and unsung. Even The Sky Boy – for all his romantic allure “lifted like Lindbergh in ecstatic solitude”, as one commentator rhapsodised – remains unidentified. The man in dungarees was simply part of a gang of structural ironworkers, who raised the building’s steel frame, leading the way upward as other tradesmen – carpenters, glaziers, tilers and stonemasons – followed in their wake.

A tight-knit fraternity of Scandinavians, Irish-Americans and Kahnawà:ke Mohawks, the ironworkers were self-proclaimed “roughnecks”, undisputed kings of constructional derring-do. As the New York Times writer CG Poore put it at the time, they spent their days “strolling on the thin edge of nothingness”.

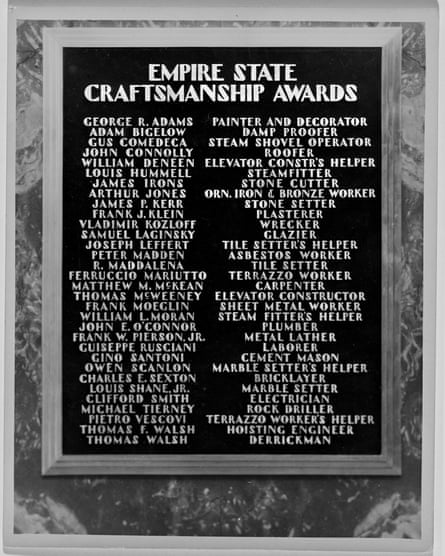

Fleshing out the men behind the myth, a new book called Men at Work throws light on the lives and opinions of a small fraction of this forgotten workforce. “My father’s office was in the Empire State Building, so I grew up visiting it,” says the author Glenn Kurtz. Familiar with Hine’s images, his interest was further piqued by a small plaque tucked into a corner of the opulent main lobby, bearing the names of 32 men who had been singled out for “craftsmanship awards” for their work on the building.

“Hine’s portraits play such an important role in the mythology surrounding not only the Empire State Building, but also 1930s America in general,” says Kurtz. “I was astonished to learn that no one had ever inquired about the men pictured.”

Bringing them into focus was no easy task. Construction workers frequently led itinerant lives, to escape “the coarse grain of official attention”. Employment records from the era were rarely preserved, and the private lives of ordinary people remained largely undocumented. This made it hard to properly record the number of people who died during the building’s creation. Although the official figure is five, Kurtz believes at least eight people perished: seven construction workers (one of which was judged a suicide) and one passerby, Elizabeth Eager, who was hit by a falling plank.

Delving into census data, immigration and union records, contemporary newspaper accounts and the personal recollections of their descendants, Kurtz illuminates Hine’s images in new ways, conjuring backstories of men who, as he puts it, “until now, have been used solely as the embodiments of generalities and abstract ideals”.

Take Victor “Frenchy” Gosselin, whose specialist skill was as a “connector”, catching a suspended beam and moving it into place to be attached to the building’s steel frame. A rare conjunction of personal details and exhilarating photos elevated Gosselin beyond the usual anonymity of the “devil-may-care cowboy of the skies”. Hine shot him nonchalantly straddling a hoisting ball in shorts and work boots, à la Miley Cyrus, an image that featured on a US Postal Service stamp in 2013.

Kurtz elaborates on the trajectory of Gosselin’s life and sudden death aged 46 in a car accident, leaving a widow and two young sons. “Distinguishing Victor Gosselin, the man, from the figure in Hine’s iconic photograph does not make him any less heroic,” he argues. “Instead, it allows us to see the photograph more fully, and it roots Gosselin’s genuine heroism in a real life, tragically short and mostly unknown, rather than in a fantasy.”

There are other no less compelling histories. Vladimir Kozloff, born in Russia, who throughout the 1930s served as secretary for the House Wreckers Union, and was active in winning protections for workers in this highly perilous profession. Or Matthew McKean, a carpenter who emigrated from Scotland, leaving behind his wife and two children. Or terrazzo craftsman Ferruccio Mariutto, who at the time of his stint on the Empire State had been in the US only two years. Like many workers, he died relatively young, just before his 64th birthday, probably of mesothelioma related to asbestos exposure.

Kurtz saves his most controversial speculation until last: that the unknown Sky Boy was a man called Dick McCarthy, a second-generation American, grandson of Irish immigrants, living in Brooklyn, who died in 1983. Although Hine never left any clues in his notes, comparison of images of McCarthy and the Sky Boy point up a tantalising physical resemblance.

“Considering the worldwide fame of this photo, it’s astonishing we do not know the name of the man,” says Kurtz. “His use as a symbol almost precludes attention to him as an actual person. We may never know the truth, but I’d say I have 50% confidence in my conjecture.”

Narratives of architecture tend to disregard the human cost of construction. History is made by the few, not the many. “The lives and experience of actual workers are marginalised,” says Kurtz. “They are too ‘ordinary’ to be interesting. Yet their skill, their training, and the specific conditions of their workplaces, are all profoundly important to architectural history. They are how every building gets built.”

.png) 3 months ago

58

3 months ago

58