An exhibition of conceptual photography that has a sense of humour? Seriously? Sprüth Mager’s new group show of that title makes its case over four floors jammed with still and moving images of clowns, costumes, Star Wars figurines, dogs watching porn, a colourless cheeseburger, and artists running over a carton of milk.

I’m absorbed by one of the most recent works in the show, Martine Syms’ She Mad: The Non-Hero, a conceptual TikTok tale inspired by Lil Nas X’s Life Story series from 2021. Borrowing the rapper’s structure and tropes, Syms performs convincingly as a rising star of the arts scene who shares her struggles with health, depression and loneliness. It’s a punchy satire of social media mores that debunks ideas about success.

I’m jolted out of this thought by a shrieking noise. ButI haven’t stepped on a joke shop trigger, it’s Louise Lawler’s seven-minute 1972-81 audio work Birdcalls, in which she calls out art world sexism by screaming the names of 28 famous white male artists in the style of different bird calls. The idea is to present nature as artifice, the same way art history is merely a constructed form of power. It is also so silly you can’t help but smile.

Lawler is part of a contingent of artists here associated with feminism and conceptualism in the 70s and 90s, a kind of confrontational, spicy humour that takes aim at feminine stereotypes in mass media and advertising. An androgynous Sarah Lucas chomps down brazenly on a banana. A suite of Cindy Sherman’s works sharply satirise feminine stereotypes found in cinema and the media. A 2018 colour work shows four coiffed, heavily madeup characters wearing colourful tulle gowns, looking at the camera with something between a smile and a grimace. They seem to be sitting in the sea, a dissonance that makes the bizarre image even more awkward. In another picture Birgit Jürgenssen wears a ludicrous 3D “housewives’ apron” in the shape of an oven. Their visual puns are a revolt against stifling gender norms and they’re effective.

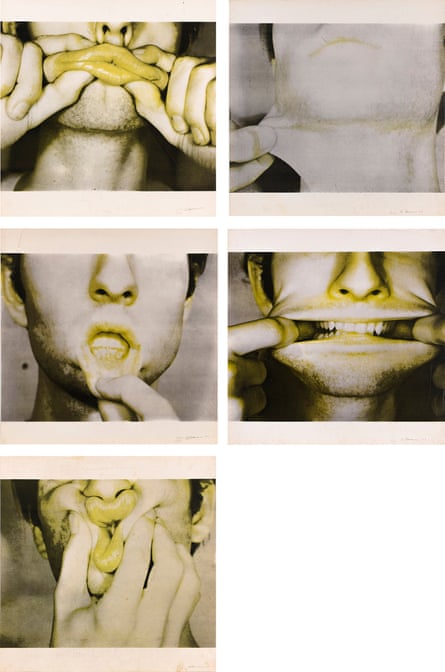

It’s great when artists don’t take themselves too seriously. The feminists were willing to make themselves look ridiculous to make the point that social codes and repressed sexual desires are farcical. Other artists adopt the strategy, too, depicting the body as a silly, plastic form that can be absurd and obscene. Bruce Nauman pulls and stretches his mouth into goofy, weird shapes. In L’Empereur series, German photographer Thomas Ruff throws himself around a room, dressed in brown and yellow to match the dour colour scheme. As he slumps and dives between the armchairs and the standing lamp, it’s a moment of slapstick for an artist not normally known for his cheer.

A range of artists find humour in objects and assemblages, such as Thomas Demand with his witty photo of a slipper stuck under a door. One wall is packed with banal and bland pictures of a vacuum cleaner, a slice of bread or a bucket – humour is subjective, sure, but they’re about as fun as a root canal.

The show starts to grate when it starts parodying other art – Ruff re-does Fischli/Weiss, Jonathan Monk nods to Lawler, John Waters sends up Gursky. But jokes don’t really work unless you get the art history references. Aneta Grzeszykowska’s recognisable parodies of Sherman – displayed in a room with Sherman – are easier to laugh at, caricatures of caricature, satire twisted into satire.

Conceptual art is often ridiculous, so it doesn’t take much to turn its bombast and pompousness into a joke. William Wegman’s Experiment has the best punchline of the show: the first of two images is captioned “As an experiment he stood on his head”. The second says: “Everything looked upside down.” One of the famous works in the show is the late British artist Keith Arnatt’s influential 1969 performance photo Self-Burial, a sequence of nine images in which the artist slowly subsides into a hole he’s dug and eventually vanishes into the ground. The photos were broadcast on German TV in 1969 for a few seconds every evening without explanation, which must have been disturbing. If many viewers may have liked the idea of an artist disappearing, the last laugh is on us, since the ground is ultimately where we’re all heading.

after newsletter promotion

The biggest laughs come courtesy John Smith’s 12-minute video shot on 16mm in 1976 and given a room to itself here. In The Girl Chewing Gum, a voice shouts directions to the action taking place on a street in London, but the director is in fact a narrator, describing the movements of unwitting passersby with increasingly fantastical relish. It’s hilarious, but also eerily prescient in its anticipation of fake news and false narratives.

This exhibition’s problem is that humour is subjective, cultural and temporal –and a lot of the gags here don’t raise a laugh today. There are a few inclusions I couldn’t figure out at all: how Carrie Mae Weems’s picture of a set of minstrel salt and pepper shakers fits in was beyond me.

Paradoxically, Seriously is less about laughter and more about humour as a tool for challenging politics and values. With playfulness and wit, conceptual artists pushed photography past the documentary into a less stable, more experimental place. But can conceptual art make you belly laugh? Probably not.

.png) 3 months ago

66

3 months ago

66