In the summer of 2018, the private investigator Simon Davison got a call from a woman who said her ex-boyfriend had stolen £10,000 from her. Carol (not her real name), a traffic manager at a local council, was not a typical client for Davison. As the director of investigations at AnotherDay, a crisis consultancy in London, Davison usually works for wary companies and wealthy individuals. A former police detective, Davison has recovered stolen cryptocurrency, uncovered secret properties owned by bankrupt business people and tracked down fraudsters to Cyprus.

Davison’s speciality is private prosecutions, a little-known area of law that allows victims to pay for justice. These cases are heard in the same courts used by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the public prosecutor for England and Wales, and they can carry the same amount of prison time for suspects. “We really mirror the process between the police and the CPS,” Davison said. The difference is that the police are agents of the state, whereas people call on Davison when the state fails to help.

Carol’s ex-boyfriend, Jiro Wilson, had persuaded her to lend him money to finance a company he was setting up. In exchange, Wilson promised her shares in his fledgling firm. “Looking back, I could see how stupid I was to believe him,” Carol later recalled in a witness statement. “He would often call me paranoid, and certainly made me feel this way when I suspected [he was] seeing other women.”

One evening, while surreptitiously scrolling through Wilson’s phone, she saved the numbers of other women in his address book, and began texting them in secret. To Carol’s horror, three women told her that Wilson had also “borrowed” thousands of pounds from them, too. Carol set up a WhatsApp group, and arranged to meet the women at one of their homes in Exeter. The four women discovered that each had been duped in the same way. “He was a disgusting narcissist,” one of them told me. In total, Wilson had stolen £46,000 from them, promising they would reap the benefits of investing in his company. He spent the money on escorts, eating out and motorbikes.

Carol reported Wilson’s theft to the police, who referred her to the national fraud hotline, which gave her a reference number and never contacted her again. The three other women also failed to interest law enforcement in their case. More than getting their money back, the women wanted justice. One contacted a solicitor in Exeter called Jeremy Asher. “It was very obvious that this was a substantial fraud committed by a very devious, calculating manipulator,” Asher recalled. “But the police weren’t interested.” Asher advised the women to bring a private prosecution. Doing so would be expensive – in the tens of thousands of pounds – but their case was so strong that Asher said the court would probably reimburse their costs. So the women cobbled together the money, and on Asher’s recommendation, Carol contacted Davison, the private investigator.

As he dug into the case, Davison found that Wilson also appeared to have fiddled his VAT returns. The judge who heard the private prosecution in December 2020 decided Wilson’s offences were potentially so serious that the CPS should take over the case. The CPS passed the case to the police, who discovered that Wilson had submitted nearly £250,000 in fraudulent VAT returns, and had stolen a further £50,000 from a government loan scheme. On 13 June 2023, Wilson pleaded guilty to seven counts of fraud at Exeter crown court. A judge sentenced him to six years in prison and described him as a “dishonest parasite”.

Had the police taken Carol and the other women’s initial allegations more seriously, a private prosecution would never have been necessary. But their experience is not uncommon. The result is that over the past decade, a parallel criminal justice system has emerged in England and Wales, staffed by lawyers who specialise in privately prosecuting crimes, and former police officers who investigate them. The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) doesn’t maintain a public record of private prosecutions, but in 2024 they accounted for a quarter of all cases in magistrates courts in England and Wales. According to one law firm, between 2016 and 2021 the number of private prosecutions more than doubled. “Fifteen years ago, they were very rare,” said Sandip Patel KC, a barrister who specialises in white-collar crime. Since then, “it’s been like the stock market going up. It’s just a vertical line.”

Some regard these prosecutions as a solution to shrinking state budgets, and a way to access justice when all other routes have failed. But the risk is that well-resourced victims can afford something denied to others. Adrian Darbishire KC, a defence barrister, told me that, in his experience, private prosecutions were typically brought by “people who can afford to spend a million, or a couple of million, if it comes to it”. The cost of investigating complex cases puts such prosecutions beyond the reach of most ordinary people. “As it stands, they fill a gap in name only,” said Nick Vamos, a solicitor at Peters & Peters, a City law firm. “If you really wanted to fill that gap, the best way to do it would be by properly funding the criminal justice system.”

In almost every conversation I had about the rise of private prosecutions, one law firm cropped up: Edmonds Marshall McMahon (EMM). “They do private prosecutions on an almost industrial scale,” said Steven Kay KC, a barrister who works on white-collar crime. Another solicitor said: “They were the first. They spotted a niche.” EMM was founded in 2012, not long after the coalition government announced drastic cuts to the MoJ. The firm’s three founders used to work as government prosecutors for the Department of Health, the CPS and the Serious Fraud Office (SFO). They are now enjoying more lucrative careers in the private sector. “We saw there was a gap in the market – that private prosecutions would inevitably grow the more that the state stepped back,” said Tamlyn Edmonds, the firm’s co-founder and managing partner. “And pretty much from day one,” she recalled, “the phones started ringing.”

There was one major type of case they were dealing with. In the 2010s, politicians often said that crime was decreasing, an idea that lent justification to Theresa May’s decision to axe 21,000 police officers while she was home secretary. But while it was true that violent crime was going down, other types were going up. In 2017, when the Office for National Statistics (ONS) began including online fraud in its England and Wales crime survey, the recorded crime rate nearly doubled.

Since then, fraud has only grown. In England and Wales, it increased by 31% in 2024 alone. Yet the police have, as a rule, shown little interest in tackling it. Several former police officers told me that it was regarded as boring. “There’s a real focus towards action. Catching a burglar and chasing them down the street,” said Mike Neville, a former detective chief inspector in the Metropolitan police. Whereas with fraud cases, “you need someone who is willing to go through a thousand pages of a spreadsheet”. Few people join the police to pore over Microsoft Excel documents. As one officer put it in a 2019 report, “Fraud doesn’t bang, bleed or shout.”

The main port of call for victims is the national hotline, Action Fraud, which was founded in 2009. When Alfie Moore, a retired sergeant in the Humberside police, used to work at a control room logging 101 and 999 calls, he would often direct callers to Action Fraud. “We thought, these kids are the dog’s bollocks. They’ve got loads of money, they’re switched on,” he remembered. “You’re not talking about some PC in Scunthorpe who has no idea.”

In reality, Action Fraud is a call centre whose day-to-day running was, until 2019, outsourced to a private US company called Concentrix, which employed call handlers who received just two weeks of training and were paid close to the minimum wage. When the Times placed an undercover reporter at Action Fraud in 2019, they found staff taking calls from victims while scrolling through their phones and play-fighting. Some of their managers mocked fraud victims as “morons”. (Concentrix lost its contract soon after the investigation.)

Data on fraud offences is patchy, but one report from 2023 found that just 6% of reports to Action Fraud were passed to the police. Of that tiny percentage, only a small fraction – 8% in 2024 – will result in a court ruling. Action Fraud is due to be replaced next year, after the Justice Committee found that it was not fit for purpose; one name under consideration for the new service is “Report Fraud”, which feels like a more honest summary of its work. (A spokesperson for Action Fraud told me this new service will lead to “better data sharing”, provide “specialist advice and support to victims” and allow the police to conduct more “effective” investigations.)

Most of EMM’s clients have previously tried Action Fraud. “They either get an automated response, or it ends up with an officer who advises that it’s a civil case, rather than a criminal case, even when it’s very clear it’s a criminal case,” Edmonds told me. Lawyers at EMM report most of their criminal cases to the police after the firm has investigated, giving the authorities another opportunity to take these over before EMM commences a private prosecution. Edmonds estimated that the firm has prosecuted 340 cases in the past five years, 90% of which resulted in criminal convictions. She could only recall two instances when the police had taken over the cases of EMM clients.

The growth of private prosecution reflects a wider trend in which vital parts of the public sector have been squeezed out of existence and gradually replaced by ad-hoc and expensive alternatives. The MoJ claims that the average cost of a private prosecution is £8,500, but complex cases that are heard in the crown courts, which deal with more serious offences than magistrates courts, can quickly reach into the tens or hundreds of thousands. “You’ll easily do half a million on a proper fraud,” said Kay. “These are expensive cases – you’ve got to do all the disclosure, hire a former police officer to investigate, and the costs rack up.”

While victims cover the upfront costs of private prosecutions, many of their costs are ultimately funded by taxpayers, whether or not their case is successful. Every time a firm wraps up a private prosecution, they ask the judge to reimburse them from central funds, a pot of government money that covers the costs incurred in criminal prosecutions. The Criminal Cases Unit, part of the MoJ, then reviews the firm’s application and decides how much money they get back. “It’s not a blank cheque,” said Patel. “But in my experience, you typically get 80% or 90% of your costs reimbursed.” Firms such as EMM charge a higher hourly rate than CPS solicitors, so private prosecutions “almost inevitably cost the state much more”, one judge said in a 2014 ruling. According to a freedom of information request, the government has paid out more than £32m to EMM to cover the firm’s fees since 2014. Between 2014 and 2019, the most recent years for which data is available, the amount the government spent on paying private prosecutors increased by more than 3,000%.

Until recently, private prosecutions were a rarity. In some cases, they were a last resort. In 1994, Doreen Lawrence brought one of the most high-profile private prosecutions of recent decades, after the Metropolitan police and CPS failed to investigate or bring the murderers of her son, Stephen, to justice. Mostly, though, private prosecutions were brought by charities and membership bodies. The Federation for the Abuse of Copyright prosecuted people for pirating VHS tapes; the RSPCA prosecuted animal cruelty. “I remember prosecuting someone who hung up cats in a garage and tortured them for his own sick pleasure,” said Carl Woolf, a solicitor who used to act for the RSPCA, and has since founded his own firm specialising in private prosecutions.

As more recent cuts have compromised Britain’s criminal justice system, there has been a new interest in private prosecutions. Between 2010 and 2014, after the coalition government ordered the MoJ to slash its budget by almost a quarter, the CPS lost 22% of its solicitors and 28% of its barristers. From 2010 to 2019, the MoJ closed more than half of all the courts in England and Wales, and sold off many court buildings. There are now almost 400,000 criminal cases waiting to be heard in England and Wales. So far, attempts at reducing this number have been fruitless, and the government has begun considering more radical solutions, such as trials without juries.

“This is why private prosecutions are becoming so popular: it takes ages for the courts to make a decision, the CPS is overwhelmed, and the courts have this massive backlog,” said Woolf. These prosecutions allow wealthier victims of crime to avoid the problem of overworked (or uninterested) police, and they can also be considerably cheaper than suing someone in the civil courts, since private prosecutors can recover their costs from the taxpayer regardless of whether they win or lose.

Private prosecutions can also be useful weapons: Darbishire, the KC, mentioned having seen cases where wealthy people “try to use private prosecutions just as a way of bullying someone, basically”. Rail companies have been particularly adept at criminalising people for minor rule-breaking in recent years, fast-tracking draconian prosecutions through something known as the “single justice procedure”. Defendants receive a letter detailing a charge, to which they must respond within 21 days. If they don’t respond (because the letter gets lost in the post, say), they can be tried and sentenced by a single magistrate, who can criminally convict them without a court hearing, using only minimal evidence. In 2023, a woman received a criminal record for using her railcard to save a total of £1.60: unbeknown to her, the railcard wasn’t valid for off-peak tickets. Last year, 74,000 of these rail convictions were quashed, after a judge ruled they were “probably unlawful”.

Far from making the system more efficient, private prosecutions are heard in the same courts as public prosecutions, so they get stuck in – and contribute to – the same bottlenecks. “There’s a long waiting list for rape and sexual assault cases – some take three, four, five years to be heard. If you asked most people, would you rather the courts be used to litigate a private financial dispute against someone’s former business partner, or for serious violent offences, most people would say serious violent offences,” Patel, the KC, told me. “Why should a private prosecution have access to publicly funded courts, free of charge, and stop public cases from going through?”

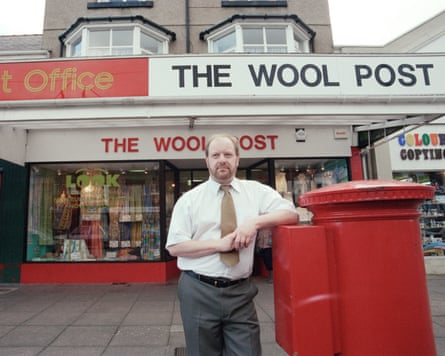

If there were a prize for the most prolific private prosecutor in England and Wales, it would go to a former police detective named David McKelvey. Through his private investigations company, TM Eye, which operates from a scrubby business park near Epping, McKelvey has seized upon the commercial opportunities afforded by shrinking police budgets and a creaking criminal justice system.

TM Eye originally investigated counterfeit cases – people selling fake designer handbags or trainers, say – which it would then hand over to Trading Standards, a government department that can bring criminal prosecutions. Designer brands would then pay TM Eye if its investigation resulted in a successful prosecution. If McKelvey’s team found evidence of a larger conspiracy, such as a gang selling counterfeits to fund drug trafficking, they referred this to the police. But over the past decade, the budget for Trading Standards has shrunk by more than 50%. With little chance of the state now prosecuting straightforward counterfeit cases, McKelvey landed on the idea of taking suspects to court himself.

McKelvey, who is 63, relishes the tradecraft of his work. When we met at TM Eye HQ, he regaled me with favourite cases, such as the time he recruited a former National Crime Squad officer and posted her to live for six months in an area of Manchester known to locals as “Counterfeit Street”, or the time his team infiltrated a Triad gang selling bootlegged tobacco mixed with asbestos dust. He showed me to the “evidence room” on the first floor, where clear plastic boxes of Louis Vuitton handbags and Lost Mary vapes had been numbered and stacked neatly on top of one another. “We started at one,” McKelvey said, patting a box. “Now we’re into the 9,000s.”

McKelvey estimates that TM Eye has prosecuted more than 1,000 counterfeit cases since 2015. One might assume that luxury brands paid a retainer to the firm, but it is taxpayers who ultimately fund many of these prosecutions. McKelvey’s firm fronts the initial costs of investigating suspects, and then passes its investigation to a law firm such as EMM, which prosecutes on its behalf. Once the case is over, the law firm applies to central funds to have its costs and those of TM Eye reimbursed. According to data obtained by the Financial Times in 2023, TM Eye had claimed costs of about £12m and been paid £6m out of central funds since it was founded. The luxury brands that benefit from TM Eye’s activities have paid nothing.

McKelvey told me that TM Eye’s private prosecutions are a “loss leader”. The real profits flow from its sister company, My Local Bobby, a private policing firm he founded in 2016. High-street shops and wealthy groups of neighbours pay MLB, as it’s known, to dispatch red-vested teams of “bobbies”, many of them former police or army officers, to patrol the streets. Unlike your average security guard, McKelvey’s bobbies conduct citizen’s arrests to detain suspects until the police arrive. Once a bobby has made an arrest, TM Eye will begin assembling the evidence for a private prosecution. McKelvey’s bobbies rely heavily on body-worn cameras, which are beamed into the Citadel, a windowless room on the first floor of TM Eye’s headquarters lit by a wall of TV screens.

Shoplifting is the most common crime that My Local Bobby deals with, and private prosecutions are the firm’s USP. The company takes a harsher approach than the police, who are more likely to give cautions for such offences. Several people I spoke with felt that the police had retreated from fighting crimes such as shoplifting and phone snatching. Three former officers, including McKelvey, told me that the coalition government’s decision to make stealing goods under £200 into a “summary offence”, which carry shorter sentences, had effectively given criminals a free pass. “These thieves aren’t stupid,” said Neville, the former Met detective. “Why nick £200 when you can nick £199 five times?”

Some have blamed the rise in shoplifting, which is now at its highest level since records began in 2001, on poverty. The connection is complex: deprivation can make people more likely to turn to crime, but not all shoplifters are poor, and many of those arrested by My Local Bobby are routine offenders who steal to fund addictions (which can also cause, or be caused by, deprivation). Even so, there is a general consensus that shoplifting has surged since the cost-of-living crisis began in 2021. Carl Woolf, who frequently prosecutes cases on behalf of TM Eye and My Local Bobby, told me that he often encounters people “who will go into a shop and steal hundreds of bottles of baby formula. They’re selling it because people need it and can’t afford it.”

Despite the growing demand for this shadow justice system, some people I spoke with worried they belonged to an industry on the verge of extinction. “We are getting mullered by the MoJ,” McKelvey said. The government has become stingier about the amount of money it awards to private prosecutors, he claimed. “In the old days, they’d sit there and go yes, yes, yes, check. Nowadays, and probably for the last four or five years, they go red line, red line, red line.”

The victims and courts bill currently making its way through parliament contains an explosive detail that could topple the entire business model. It proposes that lawyers should only be awarded “reasonably sufficient” costs from central funds. The bill doesn’t state how much would count as “reasonably sufficient”, but in theory it could mean that highly paid lawyers would suddenly find themselves earning legal aid rates, or the kind of charged by CPS prosecutors. Unsurprisingly, this idea is not popular with lawyers in the industry. “Private prosecutors are standing in the shoes of what should be a state function,” said Tamlyn Edmonds. “But the state hasn’t acted, so why should the private prosecutor be out of pocket?”

Earlier this year, the MoJ took a swipe at private prosecutors in a consultation paper, alleging that some of them had “acted unlawfully, improperly and well below the standards the public expects”. Its main target was the Post Office, which brought 918 successful private prosecutions against its post office operators between 1991 and 2015, sending innocent employees to prison for theft and fraud. In theory, it should be possible to distinguish between Post Office-style scandals and justified cases, since the CPS can put a stop to any private prosecution. In practice, it is too overstretched to monitor every case. And since there is no publicly accessible record of private prosecutions, it is hard to see how many are taking place overall, or which ones could be abusing the system. (“It appears that the only institution which was aware of the number of prosecutions being brought by the Post Office was, until recently, the Post Office,” the justice committee noted in 2020.) Sam Townend KC, a barrister and former chair of the Bar Council, described the actions of the Post Office and some rail companies as “horrific examples of the sometimes arbitrary power of large corporations to bring private prosecutions”, adding: “They have cast a dreadful shadow over the field.”

Edmonds was careful to draw a division between these recent scandals and private prosecutions in general. “There was probably far more trust in the Post Office than there is with independent private prosecutors,” she said. “There’s a huge amount of scrutiny once you’re in court.” Even so, the court should carefully consider the motives of clients wanting to bring private prosecutions. In 2021, Pradeep Morjaria, a wealthy Dubai-based businessman, instructed EMM to issue a criminal summons against a property developer called Camran Mirza, whom Morjaria was also suing in a parallel civil case. The prosecution seemed less like a route to justice than a means of using the British legal system to intimidate an enemy into settling. At one point, Morjaria emailed EMM stating that “we need serious firepower and threat of maximum jail term to bring [Mirza] to his knees”. A judge later threw out the case, criticising its “truly oppressive” nature. “The purpose of the criminal process is not to serve the private interests of any individual,” he ruled. When I asked Edmonds about this case, she said she couldn’t comment.

If such prosecutions provoke a fundamental unease, it can be because they assume a power that many people think should belong to the state. “How do we feel about the state effectively lending the keys to its tanks to a private individual, and saying, you can have fun with these for a little while?” said Darbishire, the KC and defence barrister. Edmonds and other private prosecutors I spoke with were keen to emphasise that they applied the same public interest test as the state does when deciding whether to prosecute. But unlike a CPS lawyer, who receives a salary regardless of whether they prosecute a case, EMM gets paid to bring cases, not turn them down. “The old thing that used to be said about public prosecutors was that they enjoy no victories and suffer no defeats,” said Ken Macdonald, the former director of public prosecutions. “If you’re a private law firm and your whole business model depends on bringing private prosecutions, you want to win. Your business model is: we will get you a conviction.”

If the government reduces the fees that private prosecutors can claim back from the state, the industry that has thrived in the wreckage of austerity will surely wither. So long as the government continues to deprive the criminal justice system of adequate funding, however, the demand for such alternatives will persist. During my reporting, three separate barristers mentioned the health service. They drew a parallel between private prosecutions and the clinics and surgeries that improvise expensive solutions to the problem of a decrepit public institution. In both instances, the solution only compounds the problem: when some people can buy their own criminal cases or cancer treatments, they have fewer reasons to invest in the idea of improving these things for everyone else.

.png) 4 hours ago

2

4 hours ago

2