This is how big wars start, when small ones go wrong. Nato politicians are deliberately playing with fire along the Ukrainian frontier, as UK-made missiles have been launched into Russia for the first time since the beginning of the conflict. The attack came a day after Kyiv used US-supplied long-range weapons to strike within Russia. Every military comment on British and US authorisation of missile attacks on Russia has said the same. They are “too little, too late”, and unlikely to affect a war that has increasingly turned to Russia’s advantage.

So why are the attacks happening? The answer of Britain’s defence secretary, John Healey, is that he wants to “continue doubling down” on Britain’s support for Ukraine and give a morale boost to its president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, before Donald Trump takes power in Washington. He clearly thinks the obvious risk involved in the escalation is worthwhile.

The west had been scrupulously careful in treating aid to Ukraine as strictly for its defence. Putin reacted by warning the west that any escalation in that aid to an attack on Russia by a nuclear-armed power would justify a Russian nuclear response. Then, this week, he approved changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine to declare that an attack from a non-nuclear state, if backed by a nuclear power, would be treated as a joint assault on Russia. Putin regards Ukraine – its army overwhelmingly sustained by Nato – as just such a state. He also officially redefined “attack on Russia” to cover any attack on Russian territory or that of its ally, Belarus, that posed a “critical threat” to their sovereignty or “territorial integrity”. He is clearly feeling paranoid, as has long been the custom of Russia’s rulers towards incursions on to their soil.

Nato had refused to call Putin’s bluff. Attacks on Crimea and Ukraine’s reckless invasion of Russia’s Kursk region were considered exceptions. Otherwise, the west had agreed that powerful rockets fired deep inside Russia were a step too far. Besides, Moscow has had ample time to move its supplies to new quarters.

All that this escalation seems certain to provoke is a savage Moscow retaliation against Ukrainian targets, notably energy and other utilities over the course of the winter. There may well be a wild response against “hybrid” electronic targets in the west, such as cyber-attacks on western infrastructure and utilities. It might be appropriate to ask how long the people of Ukraine are to be expected to satisfy the craving for a proxy “victory against Russia” of a succession of western leaders.

All western moves against Russia over the past two years – including the toughest ever economic and political sanctions – have served merely to entrench Moscow’s aggression. They have isolated Putin from the diplomatic pressures that customarily bring these disputes to a settlement, as with the Cuban missile crisis and the Vietnam war. They have encouraged him to savage his internal critics and draw sympathy and material support from China, India, Iran and North Korea. At a huge cost to the global economy, western sanctions have secured a new eastern trading bloc to aid Putin. Was all this not forecast by the massed ranks of thinktank Kremlinologists, or is British and US foreign policy brain dead?

Putin’s criterion for a nuclear response is impossible to imagine. The deployment of battlefield nuclear weapons is at least possible, though what tactical advantage it might yield is awful to envisage. He is an isolated dictator devoid of scruple and subject to unpredictable moods. There is also concern among western agencies at his state of mind. There can be no conceivable argument for escalating his paranoia just now, for no strategic gain.

Putin has failed in his bid to eradicate the democratic regime in Kyiv. He has succeeded, as in the Caucasus, in establishing a buffer statelet on his border. It must be the moment for compromise in the cause of peace. At present there is no evidence of any individual or institution capable of opening up such an opportunity, not the UN or Nato or any other international body.

If any lesson can be drawn from 80 years of east-west confrontation, it is that western guardians of freedom, democracy and peace have a special duty to behave responsibly in a crisis. Belligerence, machismo, risk-taking and bluff-calling are qualities that may go down well with military lobbies and tabloid media. We cannot risk them, given the current occupant of the Kremlin. Yet they are exactly what Britain’s government seems eager to do.

-

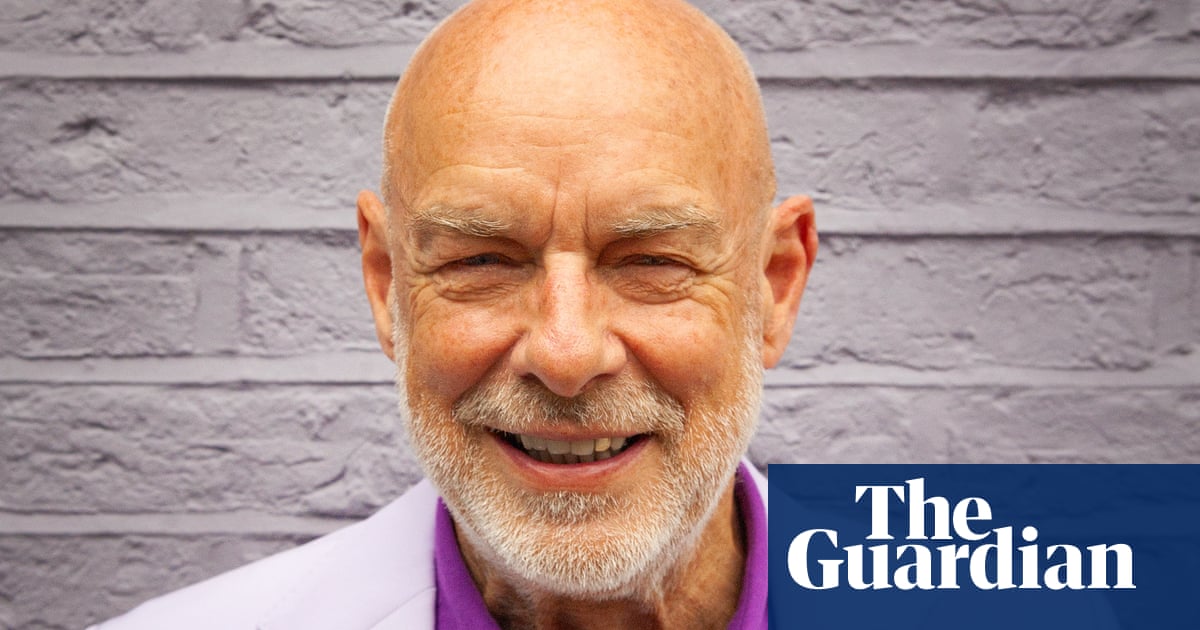

Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist

.png) 1 month ago

21

1 month ago

21