In 2009, Swiss photographers Mathias Braschler and Monika Fischer set out to document the people suffering the first shocks of the climate crisis. They had just returned from China, where rapid, unregulated development has ravaged the natural landscapes. Back home, though, the debate still felt strangely theoretical. “In 2009, you still had people who denied climate change,” Braschler recalls. “People said, ‘This is media hype.’” So the couple, working with the Global Humanitarian Forum in Geneva and supported by Kofi Annan, began The Human Face of Climate Change, a portrait series that showed the people on the frontline of a warming world.

Sixteen years later, climate change is no longer up for debate; the urgent discussions now revolve around solutions. Braschler and Fischer, too, have shifted their focus. “This is going to be one of the central issues for humanity,” says Braschler, “and we want to make sure that people know that the major effect of climate change will be displacement.”

So they returned to the road, this time to capture the bewildering moment when deep-rooted communities, some with generations of inherited knowledge, find themselves estranged from their land. The result is Displaced (2025), a sweeping, multi-year project created across 12 countries, gathering together more than 60 portraits of people forced from their homes by drought, floods, desertification, sea-level rise, wildfires, and the slow collapse of local ecosystems. It is among the first photographic efforts to approach climate displacement on such a global scale, documenting the human impact of headline-making catastrophes such as California’s wildfires alongside quieter ones. The latter might begin when a farmer notices marshland waters becoming salty, or when a fishmonger watches the coastline erode and wonders if the next wave will come tonight.

It’s devastating to lose your home in a day, and terrifying to watch it happen slowly, year after year, until one morning there’s no option but to leave. After a few hours with this collection, I feel awake to both the particularities of each loss and their collective reach. These are the brave first responders to a global catastrophe already under way; one that, sooner or later, will reach all our doors. I’m struck, too, by the rawness and dignity of the portraits. “We take time,” Fischer says. “We sit and talk with people. It’s not about getting a quick photo.” Their method is slow and meticulous: a portable studio, a backdrop, careful lighting. “People open up more when they feel you’re truly interested. They react very positively to that level of care. And they see the photos. In Kenya, the Turkana people loved seeing themselves like that. They looked proud, dignified.” Women, especially, responded strongly to Fischer, an artist doing her work with her son in tow. “To show up as a family was a huge advantage,” she says. “Displacement seems to be very much a woman’s story. Losing your home, making those decisions. It’s very much in women’s hands.”

The portraits are paired with images of homes, marshes, hillsides and coastlines now lost, damaged, or receding. In Mongolia, former herders stand before the camera after losing hundreds of animals to a historic dzud, the extreme winter that has become more frequent as the country warms at twice the global average. “We battled with snow from morning until night,” says Nerguibaatar Batmandakh, a herder now working as a security guard. “Every morning, there would be a dozen animals dead, another dozen in the evening.” In Brazil, families displaced by the 2024 floods speak to the photographers in a humanitarian reception centre in Porto Alegre. Standing beside her three teenagers, still in shock, Raquel Fontoura talks about losing her sense of purpose. “I also lost a piece of myself.” Pedro Luiz de Souza, a single father in the same camp, worries about how to tell his daughter their home is gone. “She still thinks she can go back and pick up that doll, or pick up that drawing that she liked.”

The pattern repeats across continents. In Louisiana, high-school student Alaysha LaSalle recalls looking out of the window as a 2020 hurricane tore her town apart: “All we’ve seen were our poles that our house was standing up on, and that was all that was left. No house.”

These disasters are immediately shocking, Fischer says, but equally upsetting is the slow onset of catastrophe: “when people lose their lifestyle – hundreds of years of tradition is lost now in our generation”. In Iraq’s marshlands, considered to be the cradle of our civilisation, the great wetlands of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are drying. Rasul Aoufi, a construction worker, mourns his farming life. “We had animals and we could care for them – there was water and there was food to feed them. But now, there’s no water left, no birds, nothing.” Abbas Gurain Hubaish Alammary, a water-buffalo farmer, holds his four-year-old daughter, Fatima, in his arms. “In the past, there was fishing, there was life in the marshes. But all of that is gone.”

It’s undeniable that it is easier to withstand disaster in a wealthy country – and yet those disasters get the bulk of our attention. When we talk about climate displacement in developing countries, it is often in fearful tones about mass migration to the west, even though most displacement happens within national borders and takes people only as far as they need to survive. “We hear so much about illegal migration,” Braschler says. “But we’re still talking about humans. Desperate people who have no other choice.”

“Our greatest wish as fishers,” says Khadim Wade from Senegal, “is to wake up by the sea.”

Dina Nayeri is the author of Who Gets Believed? and The Ungrateful Refugee

Senegal

Each year, the ocean inches up the shore of Saint-Louis, the country’s former capital, and more of it disappears beneath the waves, forcing families to relocate.

Doudou Sy (pictured main image) and Khadim Wade, fishers. They lost their home and now live in the Diougop relocation camp, 10km outside Saint-Louis; they have to commute to their boats in Guet N’Dar

Doudou: “Our house was the ancestral family home. We were born here and only knew this place. This painful ordeal forced us to leave our land.”

Khadim: “Not to live by the sea is truly sad. Our greatest wish is to wake up by the sea.”

Massène Mbaye (on left) and Penda Dieye, with their twins Assane and Ousseynou. They moved in with relatives after the sea took their home on the beach of Guet N’Dar

Massène: “Every year that passes, the sea digs deeper into the shore. I know we carry some responsibility; we haven’t taken care of nature. Instead of keeping our surroundings clean, we keep adding more pollution. We throw away waste that can harm or kill animals. We’re causing damage to both nature and wildlife.”

N’Deye Khoudia Ka, fishmonger. Moved to the Diougop camp after losing her home to coastal erosion

“During times of sea rise, it was very stressful. You couldn’t sleep because you didn’t know if the waves would come at night. The day we left, the focus was on how to survive and make the children leave the house as the walls fell. The destruction was total. The only positive outcome is it saved us as a family, going to a new, dry place where I won’t be stressed about when the next wave will come.”

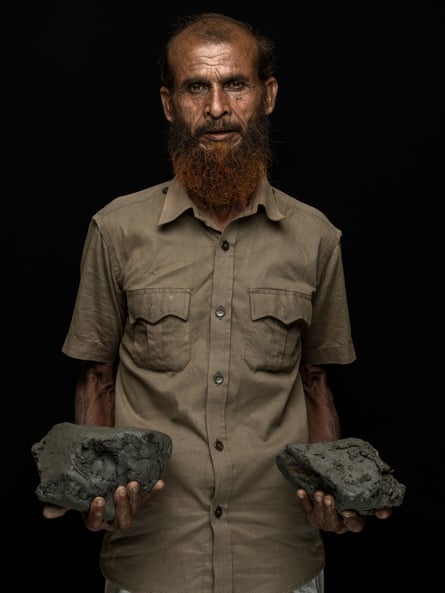

Iraq

Conflict, climate change and weak governance make Iraq the fifth most vulnerable country to climate change in the world, according to the UN, with its southern marshlands (above) particularly badly affected.

Abbas Gurain Hubaish Alammary, water-buffalo farmer, and his daughter, Fatima. Drought forced them to move from the Sinaf marshes to a nearby settlement

“The water has turned salty and the marshes are dry. In the past, there was fishing, there was life, but all that is gone. When I go back, I remember how sweet life used to be. When I see what it has become, I feel like I’m dying. What can we do? This is life – today you’re in one place, and tomorrow you’re forced to be somewhere else.”

Mongolia

Over 70 years, the country’s temperatures have risen by 2.1C, which is about double the global average. Extreme cold events have caused many herders to abandon their nomadic lifestyles.

Anartsetseg Erdenebileg, student. Relocated to the town of Baruun-Urt in Sükhbaatar province

“Living here in the provincial centre is very different from life in the countryside. The air is polluted, and I feel like we get sick more often because of it. I miss the fresh, clean air of the countryside – it felt healthier, and I could breathe freely. That’s the kind of life I want again, out in the open, where the air is pure and the land is wide. That’s where I truly feel well. Even after everything, I still dream of being a herder. I want to return to that life.”

Yanjmaa Baljmaa (left) and Nerguibaatar Batmandakh. The former herders now work as a nurse and a security guard in Baruun-Urt

Nerguibaatar: “We had two herds of horses, 200 sheep and goats, and 10 cattle. It was bad everywhere in the winter of 2023. We sent our horses to the east and tried to save our cattle and small animals throughout the winter, but to no avail. We battled snow morning till night. The hay and fodder we reserved were not enough; every morning, there would be a dozen animals dead, another dozen in the evening.”

Yanjmaa: “I couldn’t stop crying when I saw them dead. It was devastating to see the animals I had taken care of perish like that.”

Germany

In 2021, severe flooding in the Ahr valley (above), west of Bonn, killed 134 people and injured 766; at least 17,000 suffered the loss of, or damage to, their homes.

Walter Krahe, lecturer. His house was next to the Ahr River

“If we don’t start taking real action, well, what shall we call it? Decline? Downfall? With every day, with every month, with every year that we wait and don’t take really crystal-clear measures, we slide more towards uncontrollability. Yes, we are afraid of change. But the changes that will happen if we do nothing are much worse.”

Christian and Sylvia Schauff, retired. Lost their home in the town of Erftstadt

Christian: “I didn’t grasp what was happening until we were outside, trying to swim for safety. Furniture, garden tables, even a car rushed past us, swallowed by the water. I honestly believed we wouldn’t make it out alive. If it hadn’t been for the strangers who reached out, we never could have survived. And just like that, it was over – for now. ”

Sylvia: “We just drift from one day to the next. I am now fully retired because I can no longer work. I barely sleep. And all of this, for me, is tied to the loss of my home. I feel uprooted – torn out of the ground that once held me.”

Kenya

Drought has become a major threat to the Turkana people in the north of the country (above), while floods are increasing in severity in the Tana River area of the south.

Lokolong (left) and Tarkot Lokwamor, former pastoralists now farmers, with their children Ewesit, Arot, Apua and Akai. Relocated to a refugee camp in Kakuma, Turkana

Tarkot: “The worst thing is that the weather changed. There is no more rain. Every year now is the same – drought, drought, drought. This has really hurt us.”

Nakwani Etirae, pastoralist turned farmer, pastor and shop owner. Relocated to the Kakuma refugee camp

“I used to have a lot of animals – more than 600 goats, 27 donkeys, cows and camels. I lost them all in the drought. We were depending on those animals, for milk, meat and a lot of other products. Finally, we had to move here, close to the refugee camp in Kakuma. Now, I only have 17 goats and some chickens.”

Maryam Atiye Jafar, pregnant with her first child. Relocated to Mtapani camp, Tana

“It’s very challenging to give birth in this environment, because the tent is too small and the huts are constructed with tarpaulins. It’s very hot. I am thinking of how I’m going to bring up my child in this heat.”

USA

Cameron, in southern Louisiana (above), nestled in the Gulf of Mexico, has been devastated by a series of hurricanes, most recently Laura and Delta in 2020. Some residents have rebuilt four times, but most have left. Fewer than 200 people remain in what was once a bustling community with almost 2,000 residents.

Alaysha LaSalle, student. Her family home in Cameron was destroyed; they now live in Lake Charles, a city 40km away

“All I remember is whenever we looked outside, we just saw a lot of things flying. I was scared. I waited until the hurricane was over and went outside, and it was damaged, like really badly. All we’ve seen were our poles that our house was standing up on, and that was all that was left.”

Guatemala

The country is in the Dry Corridor, an area in Central America marred by failed harvests due to unpredictable rain patterns responsible for drought and flooding. In recent years, the effects of climate change have further fuelled migration. Guatemala ranks ninth in the world for level of risk to the effects of climate change.

Maria Gonzalez Diaz, housewife, with daughters Maria Eulalia and Adelaida, who fled their village to the city of Nebaj after a mountain landslide

Maria GD: “When it was time to harvest, it started to rain a lot and then it all dried up because of the hot sun, and that was it, we didn’t have any more crops. I came here to Nebaj because there was no food in my village. Here at least my children can eat. Maybe it’s not meat, but at least they have tortillas.”

Ruben Sanchez Perez, farmer and father of seven. He lives in a village in the province of Huehuetenango

“My sons Wilmer and Amilcar left for the US – there was no other way to survive. There was no work, no money, nothing. They walked through the desert, risking their lives, but thank God, they made it. They send a little help. Others weren’t so lucky. Some came back with nothing but debt and pain. It’s scary. But here, the land no longer gives – and as Indigenous people, we live from the land. Without rain, we have nothing. That’s why my sons had to leave. Staying meant losing everything.”

Ileana Cha Lopez, housewife, with Amaoilis and Kimberly, who fled to Qotoxha, Panzós after flooding

“Year after year the floods were getting worse. What we planted was dying. We made the decision to look for something better.”

Brazil

In 2024, torrential rains triggered catastrophic floods in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, destroying places such as the Ilha da Pintada (above) and displacing approximately 580,000 people. It was one of the worst natural disasters in Brazilian history.

Pedro Luiz de Souza, a general services worker, and his daughter, Luizza, lost their home on the Ilha dos Marinheiros to flooding. They are now living in a humanitarian reception centre in Porto Alegre

“I’m not sure how I’m going to tell my daughter our place doesn’t exist any more. She still thinks she can go back and pick up that doll or that drawing she liked. But there is no more home. So I’ll keep fighting for her. She is everything I still have.”

Britney Louise Lima, singer and cook, lost her home in catastrophic floods at the end of April 2024 in Porto Alegre and also now lives in the humanitarian reception centre

“I often think about the future, and the first image that comes to mind is a massive iceberg melting, with all of us sinking into the waters. In the future, Brazil’s coastline will disappear – the first state to go will be Rio Grande do Sul. I plan to head north and hopefully secure a place where I can be safe.”

Bangladesh

Climate change is driving sea-level rise, flooding, stronger cyclones and erratic weather, threatening agriculture and displacing communities, especially in coastal areas. In the Khulna district in the south, vulnerable populations are being forced from rural, coastal areas to urban slums, such as Notun Bazar (above).

Firoza and Nasima Begum, mother and daughter in law, are fishers displaced three times. They now live in Nalian, Khulna

Nasima: “I feel emotionally drained from having to move so many times. Each time we’re hit by a flood or storm, we have to rebuild. I often need to borrow money just to fix our house, and it’s humiliating. I used to raise goats, chickens, even a cow – they were like family. I lost them all to the floods.”

Abdur Rashid Gazi, labourer who is building higher ground for his house in Nalian to avoid future flooding

“Before, the water wasn’t this high. Now, the river keeps rising and the land feels like it’s sinking beneath our feet.”

Fatema Begum, widow. Displaced and now living in Notun Bazar

“When I think about the home I lost, I cry. It wasn’t much, but it was mine. It breaks your heart when the life you built gets destroyed. We now live in a rented room in a slum – one small room for all of us. The rent is 2000 taka (£12.50). The landlord is always threatening to evict us because we often can’t pay the rent on time.”

Switzerland

In August 2024, an extreme precipitation event took place in Brienz (above). In less than an hour, approximately 100mm of rain inundated the area, devastating homes and businesses, and severely damaging or destroying infrastructure.

Bruno Lötscher, vet, who lost his house in Brienz, pictured with his donkey Lola

“Yesterday, we were in Berne. The people there walk around like normal, while over here it looks like a bombed-out street in Ukraine.”

Philippines

The archipelagic country is prone to extreme climate events. In October 2024, typhoon Kristine made landfall on the main island of Luzon, triggering flooding and landslides; Bicol (above) was one of the worst affected regions.

Ailyn Reolo Fermano, housewife and mother of six, is living in the Libon evacuation centre, Albay, Bicol

“It was not a usual typhoon, it rained much harder and longer. We couldn’t imagine how much it would affect us, what it would cost us, that we would lose everything we had built up over years and years. I feel so sad because practically all we had is gone.”

Joan Resuena with her children Crystal Faye, Avie James and Mark. They are now living in the Libon evacuation centre

“Here in the Philippines, I don’t think there’s any place that’s truly safe. In some regions, like this one, we face typhoons that can cause landslides, and many other places are prone to flooding. It feels like no matter where you go, there’s always some kind of risk.”

.png) 3 months ago

80

3 months ago

80