Joe MacInnis admits there are simply too many places to begin telling the story of life in the ocean depths. At 88, the famed Canadian undersea explorer, has many decades to draw on. There was the time he and a Russian explorer and deep-water pilot, Anatoly Sagalevich, were snagged by a telephone wire strung from the pilot house of the Titanic, trapping the pair two and a half miles below the surface.

Another might be the moment he and his team stared in disbelief through a porthole window at the Edmund Fitzgerald, the 222-metre (729ft) ship that vanished 50 years ago into the depths of Lake Superior, so quickly that none of the crew could issue a call for help. MacInnis and his team were the first humans to lay eyes on the wreck.

It could also be the time he led an expedition in the Canadian high Arctic, battling unforgiving ice to locate a lost British vessel crushed by those same elements.

Or, when diving in waters off the Florida Keys “humming with history”, he passed a pod of lobsters clustered in a reef that was composed entirely of 16th-century silver bars from a Spanish galleon.

But for MacInnis, a doctor, diver and writer, the place to start is simple: the shipwrecks themselves, moments when worlds were torn apart by the raw power of the ocean. The ships have helped him better understand the natural world and, increasingly, himself.

-

MacInnis diving in Lake Huron, off Tobermory, Canada, in 1969. Photograph: Don Dutton/Toronto Star/Getty Images

“In the final arc of your life, you start thinking of shipwrecks differently and they become a metaphor for understanding the forces of the world,” he says from his Toronto home. “Because, above all, they help us grapple with one of the toughest things that we have to do as humans: to reckon with the reality that we’re mortal.

“Death is coming for us, but it gives life an unexpected beauty and a deep sense of urgency,” MacInnis adds.

Nearly all of the space on the planet where life can exist is found in the oceans – and yet it remains the least explored part of Earth. Still, those who spend their lives enveloped by the timelessness of the oceans experience a power that has coaxed explorers to risk their lives for a chance to unspool the smallest of its mysteries.

Among those on the leading edge of discovery, few have encountered as many giants as MacInnis, whose career dovetailed with a golden age of undersea exploration.

“I worked alongside pioneers and I saw what was possible,” he says of an era that, alongside friendships with Jacques Cousteau, Robert Ballard and Buzz Aldrin, included a secretive US navy project to see if humans could live deep underwater.

“But I also saw the unforgiving nature of the ocean. I saw injury and death. In the final arc of my life, I want to take what I’ve learned from it and share. It will always be the greatest of all teachers.”

MacInnis, described in a 1971 issue of Popular Mechanics as a “a rip-roaring, life-loving young Canadian”, has long been one of the ocean’s most eager students. He was the first to dive at the north pole and the team he led was both the first to build a polar dive station – the Sub-Igloo – and the first to film narwhal, bowhead and beluga whales underwater.

He took Canada’s former prime minister Pierre Trudeau diving in the Arctic. He also accompanied King Charles, who was then aged 26, under the ice.

-

MacInnis, left, in the Sub-Igloo, with Don King, whose company made the polar dive station’s plastic domes. Photograph: Ron Bull/Toronto Star/Getty

-

The Russian submersible pilot Anatoly Sagalevich, with whom MacInnis got stuck in the wreckage of the Titanic, above left, and Prince Charles diving under the Arctic ice at Resolute Bay, Nunavut, Canada, in 1975. Photographs: Dmitry Kostyukov/AFP/Getty; PA

MacInnis was involved with the French and American team that located the final resting place of the Titanic in 1985. Later, he was part of a Canadian-Russian expedition to film a documentary about the wreck. During the final dive, he and the submersible pilot Sagalevich were momentarily trapped atop the ship.

He remains convinced that those years of collaboration between nations, in the pursuit of science, were a “tiny step” in the collapse of the cold war and the coming breakdown of the Berlin Wall.

“Here we were, working on science together in the ocean with two cold war enemies. And I think that reflects what shipwrecks have taught me: in moments of crisis, we need each other. We’re in this together; none of us is as good as all of us.”

In 1980, five years before the Titanic was discovered, he led a Canadian expedition to locate HMS Breadalbane – one of the ships dispatched in 1853 to help in the search for HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, lost on Sir John Franklin’s doomed expedition to chart the Northwest Passage.

The discovery of HMS Breadalbane made it the northernmost wreck ever found. MacInnis later sought out the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, a wreck preserved by the cold, clear waters of Lake Superior on the borders of Canada and the US, as well as in song by the Canadian folk-music hero and friend, Gordon Lightfoot.

“Does anyone know where the love of God goes,” wrote Lightfoot. “When the waves turn the minutes to hours?”

The question posed by Lightfoot in what MacInnis called “the song for all shipwrecks” captures the intense focus of the explorer, whose passion in recent years has drifted away from the science and technology behind the wrecks, and more towards the human psychology of them.

“When the world is ripped out from you, when it’s shredded before your eyes, how do you react? For me, wrecks have always been about the people who survived – or those that didn’t. Because in our own lives, we can at times find ourselves scrambling to get to shore,” he says. “I like to say that after years in the ocean, I’m an alpha coward with a PhD in fear.”

-

The freighter Edmund Fitzgerald, pictured in 1959, was lost in a storm on Lake Superior in 1975. Photograph: AP

Braiding together ideas of fear, chaos and decision-making has given MacInnis an outlet for his energy. His most recent book is about leadership and he has grown increasingly fixated on the relationship between wrecks, survival and the global polycrisis – a term cribbed from a good friend – that captures the challenges of geopolitical chaos and climate crisis.

“I am old and when you think about the ships, the subs and the planes I used, my carbon footprint is enormous. This is why I’m on fire right now, to do what I can to help.”

MacInnis recently suffered a heart attack and a minor stroke – and with it an uncomfortable glimpse of his own mortality. “My soft pink body, with its 2,000 moving parts and 100,000 biochemical reactions, is slowly falling apart. I don’t have the sharpness I used to.

“I’m frantically trying to put together my own lifeboat with the help of some wonderful people. But I know the shore lies at an infinite distance from where I am. For the first time, really, I’m in my own shipwreck.”

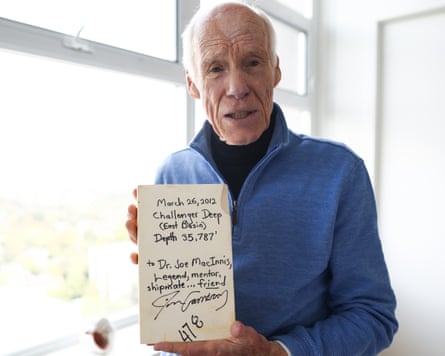

His home has numerous items from the deep sea, including a piece of foam from the submersible used – and signed – by James Cameron in his historic solo dive to reach the deepest place in the ocean.

“To Dr Joe MacInnis,” it reads. “Legend, mentor, shipmate … friend.”

-

Clockwise from top: MacInnis with the film-maker James Cameron; a rusty link from HMS Bounty’s anchor chain; and holding a signed piece of Cameron’s submersible. Photographs: Canadian Press/Alamy; Cole Burston/Guardian

He also has a rusty link from an anchor chain. Measuring nearly four inches long, it comes from the wreck of HMS Bounty – a story of maritime disaster that captivated him as a young explorer – and one that he now realises he misunderstood.

In 1789, the acting lieutenant, Fletcher Christian, led a mutiny against the captain, Lt William Bligh. Put into an open launch with a few loyal crew, the captain navigated more than 3,600 nautical miles (6,600km) from Tonga to safety in Timor. The mutineers eventually sailed 1,350 miles to remote Pitcairn Island and settled there.

“I thought of it as a story of mutiny. There were clear villains and heroes. And yet now, when I think about the crew and Christian, travelling so far on the open ocean, I see it as an incredible story of survival and leadership,” says MacInnis.

“And so there’s a sense of hope that comes from shipwreck, from the lifeboats we find ourselves in. It’s not a wishy-washy hope; it’s hope in action, it’s doing the right thing.”

MacInnis says a life spent alongside people looking to push the upper limits of human possibility has instilled within him a relentless optimism.

“If enough of us can get together and put the planet ahead of ourselves, we’ve got a chance with this. We really do.”

.png) 2 months ago

55

2 months ago

55