First there was Beginning. Then Middle. And now David Eldridge’s superlative trilogy about different couples at successive stages has come to a close with End. All three can be appreciated individually but the final play, which opened last week at the National Theatre in London, poignantly overlaps with its predecessors. If you’ve seen the other two, you can’t help but draw connections between them as much as you may find familiarities with your own relationships. Before too long, an enterprising theatre should stage all three plays together.

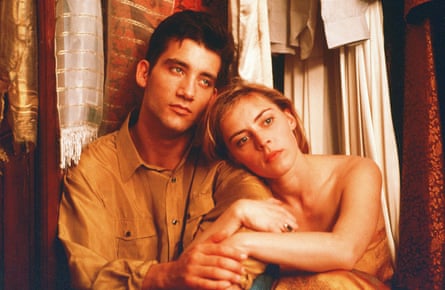

Beginning charted the drunken burgeoning of romance between a pair at a house party who are on each side of 40. Middle is about a marriage in crisis, with a young child also in the equation. Tenderly directed by Rachel O’Riordan, End finds Alfie and Julie squaring up to his cancer diagnosis after spending decades together. But the casting of the new play gives it an extra resonance as it reunites Clive Owen and Saskia Reeves more than 30 years after they starred together in Stephen Poliakoff’s Close My Eyes. I found the memory of that 1991 film complements the play enormously.

Inspired by Poliakoff’s 1975 play Hitting Town, Close My Eyes caused a tabloid frenzy for its explicit depiction of an incestuous affair between Natalie (Reeves) and her younger brother, Richard (Owen). The film has a similarly elegiac tone to Eldridge’s play partly because of the nature of its relationship, which is doomed before it begins. As well as that eventual implosion, Poliakoff offers other endings. Close My Eyes opens with Natalie’s recent breakup, the divorce of her and Richard’s parents lingers in the background and Richard’s colleague, who has Aids, is dying. As Natalie’s new husband, Sinclair (Alan Rickman), puts it towards the finish: “Something tells me it’s the end of the party.”

Natalie and Richard’s relationship unfolds partly amid the regeneration of Docklands in London and is set against a society in flux and the burst of ruthless Thatcherite individualism in the 80s. Some critics saw their incest as symbolising the era’s moral decay and urban decline – Poliakoff has a character make this comparison in Hitting Town. But in the film the couple’s union is presented as a retreat from a world shown to be not just politically corrupt but also disrupted by the horror of the Aids crisis and climate chaos. Poliakoff told the Observer when the film was released: “If you were to say, ‘Why use this taboo?’ I’d say I want the film to be a seductive experience under the shadow of twin worries – the weather out of kilter and the threat of Aids. As with all my stories, I’m trying to get into the subconscious, so that the story hangs around. I wanted it to have a haunting, end-of-decade, end-of-century feel.”

Eldridge sets Natalie and Richard’s personal turmoil against one of the most divisive periods in recent British political history. End takes place one morning in the summer of 2016, a week before the Brexit vote. That is mentioned in passing by Natalie but Richard is more preoccupied with a greater upheaval: his beloved West Ham’s departure from Upton Park after more than 100 years. When he speaks of his career as a DJ, providing people with sparks of dancefloor joy in a dark and unpredictable world, it brings to mind Richard and Natalie hiding away for illicit afternoons that are presented as almost being out of time.

The memory of the intense sex scenes in Close My Eyes (“One feels almost embarrassed to be caught watching,” wrote Stephen Holden in the New York Times) also serves to heighten Eldridge’s play. Natalie and Richard are at times literally and almost comically hot under the collar as they are consumed by an addictive, obsessive relationship – in one scene she insists that he stay on the other side of the room as she attempts to subdue their passion. In End, Owen and Reeves each have a beautifully nuanced physicality reflecting the easy comfort of decades together as well as an unavoidable sense of distancing. Early on, Alfie wonders aloud if they will ever make love again. His illness means he uses a crutch and moves awkwardly; as he stands motionless and plays a house music track in contention for his funeral playlist, she dances playfully and seductively around him.

That moment is then echoed in the rarest of theatrical sex scenes (intimacy direction by Bethan Clark). Unlike the artfully framed, ample nudity of Poliakoff’s film, Natalie and Richard have a quick shag on the sofa, almost fully dressed. Both actors expertly bring out their characters’ vulnerabilities, their ease with and care for each other, their love and fear. It has humour, melancholy and absolute authenticity in a short and sweet evocation of their more youthful passion and abandon.

When actors reunite to play couples it’s often as the same characters in a sequel but when the roles are new, they can’t help but bring the ghosts of their predecessors. In End, I was reminded of Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer playing the emotionally weathered Frankie and Johnny eight years after starring as Tony and Elvira in Scarface and the contrast between their dancefloor encounter at a flashy club in the earlier film and the homely, ramshackle party they attend in the later one.

Actors’ previous roles can cleave to them, something directer Jamie Lloyd often exploits, although I was already struggling to buy into the characters of his West End Much Ado About Nothing before Tom Hiddleston and Hayley Atwell were accompanied by full-length cardboard cutouts of their Marvel characters. End is altogether more powerful in evoking its stars’ screen history. When Alfie recalls his cocksure, “baby-faced” old self, you flash on Owen’s TV role as Chancer as well as the smoothly dressed Richard. The suaveness of his past roles (remember when he was touted as the next James Bond?) accentuates the wincing, tracksuit-wearing Alfie’s dishevelment; his first appearance, standing stiff with a haunted look in his eyes, provokes a double take. In a strange way, Julie’s success as a novelist in Eldridge’s play helps to fulfil the thwarted creative ambitions of Natalie in Close My Eyes.

Poliakoff’s film is frequently paradoxical; the nature of their relationship means that even in the first flush of their romance, Natalie and Richard share the well-worn squabbling of siblings and have a whole history as brother and sister to unpick. Like End, it’s poised between the past and the future. Even though the spectre of a possible pregnancy (emphasised in Hitting Town) does not loom in Close My Eyes, a general unease about what lies ahead is often voiced by Rickman’s character, who has made a fortune through stock forecasts.

Eldridge’s play painfully imagines the family’s life without Alfie, a future that Julie finds she can only process by plotting it as if one of her novels, much like Alfie, navigates his send-off in terms of a DJ choosing the right banger. The dancefloor becomes a convincing motif for the stages of the trilogy – it’s a place where Alfie has seen first kisses and breakups – and Eldridge draws a nice analogy between storytelling as choosing the right records as well as finding the right words. While End was written without Owen and Reeves in mind (props to casting director Alastair Coomer for bringing them together again), their old film gives this superbly performed new play a remarkable charge of intimacy.

-

End is at the National Theatre, London, until 17 January

-

Chris Wiegand is the Guardian’s Stage editor

.png) 3 months ago

60

3 months ago

60