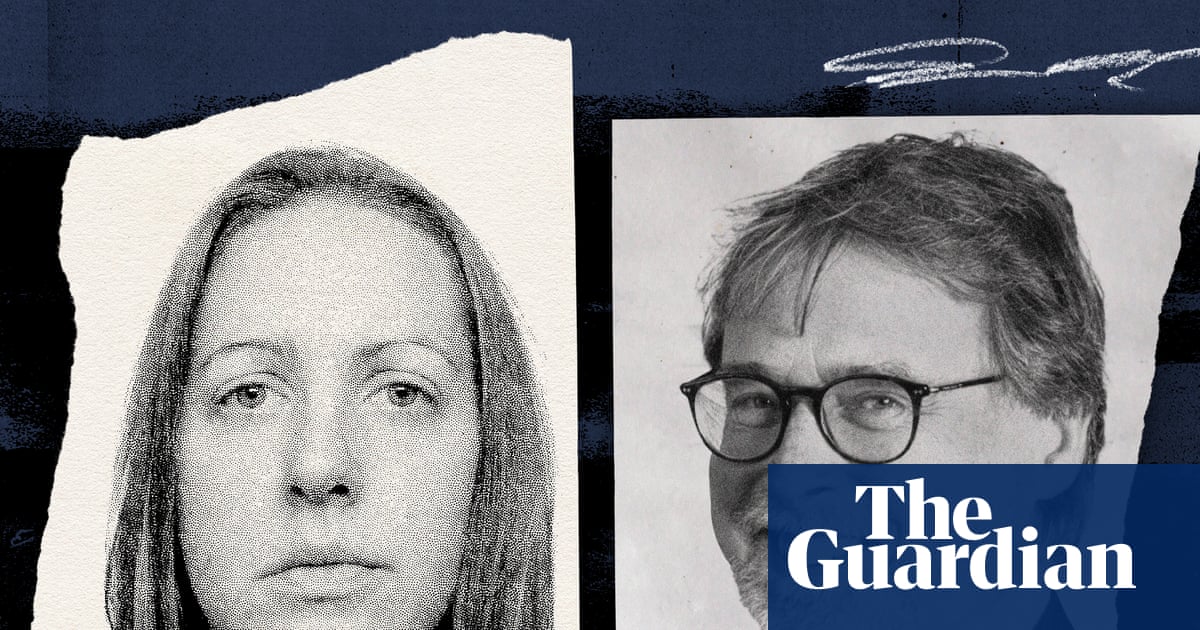

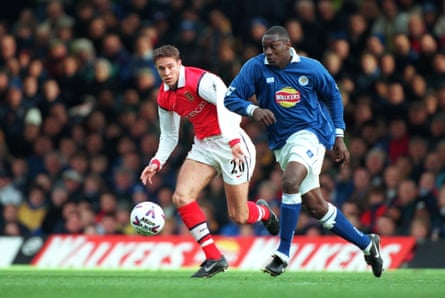

Emile Heskey was about 14 years old when he was chased from Leicester City’s old Filbert Street stadium all the way into town by a man shouting racist abuse. He was a Leicester fan who had no idea he was abusing a player who would go on to help his club win promotion to the Premier League and two League Cups before a move to Liverpool for what, at the time, was the club’s record transfer fee.

“Fast forward three years that same guy would’ve been chanting my name in the stadium,” Heskey says now. “This is our reality.”

The former England striker is discussing the racism he experienced during his playing days to explain part of the motivation for creating the Football Safety App, a new online tool through which fans can report football abuse. And his stories are harrowing. There was the time he left another stadium with two of his sons, Jaden and Reigan, the promising Manchester City teenagers, and someone racially abused them. They were four and six.

“They were kids so I don’t think they would’ve understood what was going on,” Heskey says. “We were walking from a stadium and something was said – I won’t say what. But you just leave it and move on. They would’ve been in a stadium watching me play when things were being chanted.

“I don’t think much has changed. If anything, social media has made abuse worse. You’ve got access to abuse anyone you want at any given time. I think there would be similar sorts of crime and abuse at stadiums. But now this is terrible.”

It is a particularly bad place for women in football. Heskey has worked for Leicester’s women’s team in various roles since 2020 and seen first-hand the toll it takes. Things have particularly intensified since the Lionesses’ huge success drew a brighter spotlight on women’s football. “We’ve had girls struggling with the attention that you get as a professional,” says the 47-year-old. “Why are female commentators getting abuse more than anyone else? How can we report it? And how do we get convictions? Something that is tangible and makes people sit up and realise they can’t come on here and hurl abuse because they feel like it.

“Gone are the times when you say don’t listen to them, turn the other cheek. Just ignore them. No. Why should the girls ignore abuse? We’ve had it for years where we’d just ignore it. Who are we to say ignore it? We should be helping them report it, to make them feel OK in that space.”

The Football Safety App, which feeds reports to a central hub of security professionals who liaise with stadium staff and police, “is not about racism, it’s about everything,” Heskey explains. It was born out of his desire to make football a safer space and to protect his two sons taking their first steps in the professional game.

Reigan, 17, and Jaden, 19, came on for their City debuts in a Carabao Cup game against Huddersfield in September. “My sons are now stepping into that same limelight. I was looking at how we can protect these children. How can you protect females? How can you protect everyone who wants to enjoy the game we love?” Has Heskey ever spoken to them about racism in football. “No,” he replies. “It’s not an easy topic to sit down and explain why [racists] they’re doing it, because I don’t know why they’re doing it. We’ve seen it. They’ve seen it. They’ve seen me go through it. They’ll understand it. They’ve got good friends, a good family network, so they’ll come to us when something happens.”

Reigan was recently challenging for the Golden Boot at the Under-17 World Cup in Qatar until England were knocked out by Austria in the last-16. Heskey travelled to watch a match and afterwards his ears pricked when he heard familiar calls. “Everyone was shouting ‘Heskey! Heskey! Heskey!’ and it’s not me,” he says. “I was looking around. No one’s calling out for me.”

Heskey only gives his sons advice when asked and made a point of being invisible when he watched them play in City’s academy. “I stood back when they were young. One thing I didn’t like to see was when kids keep looking over at their parents. You’ve got to be focused.”

He particularly didn’t like hearing parents shouting at their children from the touchline. “I grew up in an era where your parents were never in a training session. Your focus was the coach,” Heskey says. “Now every parent is at training, and everyone is like this [he looks frantically left and right] so you’re not focusing on what the coach is delivering.

“They [Reigan and Jaden] never saw me at the training ground. I was there but I stood that far back no one would see me. I liked them to concentrate on the training, otherwise they’re not learning. And if you’re constantly looking over at your parents it’s not good for you.”

Like everyone else, Heskey has been surprised by the sharp decline of Liverpool, a club where he won several trophies during a four-year spell following his £11m move from Leicester in March 2000. There was a 2-0 victory at West Ham, a 1-1 home draw with Sunderland and a 3-3 draw with Leeds following a run of nine defeats in 12 games that represented the Premier League champions’ worst run in 71 years.

Speaking before Mohamed Salah’s explosive comments in which he claimed he had been “thrown under the bus” after being left out of Liverpool’s starting lineup for a third game running at Leeds, Heskey recalls that during his time at Anfield, under Gérard Houllier, the team were told they could never lose two games in a row and how that ultimately motivated them. “There were times we lost two or three in a row, but we’d fight to put that to an end,” he says. “We had fighters. They’ve probably got more technical players now.”

“The difficult part is when you’re in a tough position, who’s going to dig you out? They had players to dig you out before. I’ll give you some from my era. Stevie [Gerrard] would dig you right out of a hole. Michael [Owen], he’d dig you out of a hole with goals. [Jamie] Carragher would dig you out with his tenacity and fight, and the screaming and holding you accountable. Where’s that? I haven’t seen it.”

He adds: “We never really had all our players in a rut at the same time. They. [the current team] seem to have that,” Heskey adds. “Generally, you look towards someone who is a bit of a talisman who says,: ‘Come one.’ I don’t think Virgil [Vvan Dijk] is having a great time, Mo [Salah] isn’t having a great time. Who are they looking to? Someone’s got to step up.”

Speaking to Heskey it is clear that making football a friendlier space has become a passion for him. “Football is for everyone. We all love it,” he says. “I’m not loving Liverpool right now, but we all love it. We’ve just got to make it a place everyone feels safe.”

.png) 2 months ago

60

2 months ago

60