Indigenous and environmental leaders in Ecuador say they are facing a wave of state intimidation ahead of a national referendum next month on whether to rewrite the world’s only constitution that recognises the rights of nature.

The pressure is being applied by the rightwing president, Daniel Noboa, who has begun his second term with a Trumpian agenda of consolidating power and sweeping away legal and social barriers to extractivist businesses, such as mining.

The 37-year-old heir to the powerful Noboa family business group says the existing constitution is an obstacle to his national security and economic development agenda, which includes the construction of a US military base and new housing and hotel complexes on the Galápagos Islands, a Unesco world heritage site and biosphere reserve.

The referendum on 16 November will decide whether to establish a constituent assembly to reform or replace the constitution, a process that would enable the president to put pressure on the main organisation that is resisting his push for more power: the constitutional court. It will also address several other far-reaching changes proposed by Noboa, including a reduction of seats in the legislative assembly, party funding and foreign military bases.

The referendum will be the most controversial move yet by the president, who has already prompted alarm with several pieces of legislation that critics say undermine environmental safeguards and democratic checks and balances.

A protected areas law, for example, purportedly enhances environmental sustainability and the management of conservation areas, but Indigenous groups say it is a ruse to bypass their right to free, prior and informed consent, while potentially opening up protected land to privatisation and extractive industries.

A national solidarity law was ostensibly passed to strengthen the government’s authority and resources to tackle organised crime, but it has been used, say observers, to militarise public security and provide impunity for police and military killings carried out in the name of a war against gangs. A new intelligence law has given unprecedented surveillance powers to the administration, which can intercept communications without a court order. Meanwhile, a public integrity law, which claims to tame corruption, has become a tool to crack down on civil society.

Social unrest has mounted steadily in Ecuador. The country has one of the highest homicide rates in the world. Rising prices of food and diesel have added to the tensions, prompting an ongoing national strike. Last month, an Indigenous land defender, Efraín Fueres, was shot and killed by the army during a protest against the high cost of living, a lack of medicine in hospitals, the deterioration of schools and growing social insecurity.

Demonstrators are also angry that at least 61 civil society leaders and organisations have had their bank accounts frozen, pending an “unjustified private enrichment” investigation by the public prosecutors office.

The Guardian has seen a list of those facing persecution. More than half were Indigenous activists, several of them campaigning against mines. Another quarter were environmental defenders. The rest were academics, journalists, women’s rights activists and local politicians.

Among those under scrutiny was the Pachamama Foundation, which released a statement saying it would resist this attempted intimidation. “We categorically reject the criminalisation process that has been initiated,” thefoundation said.

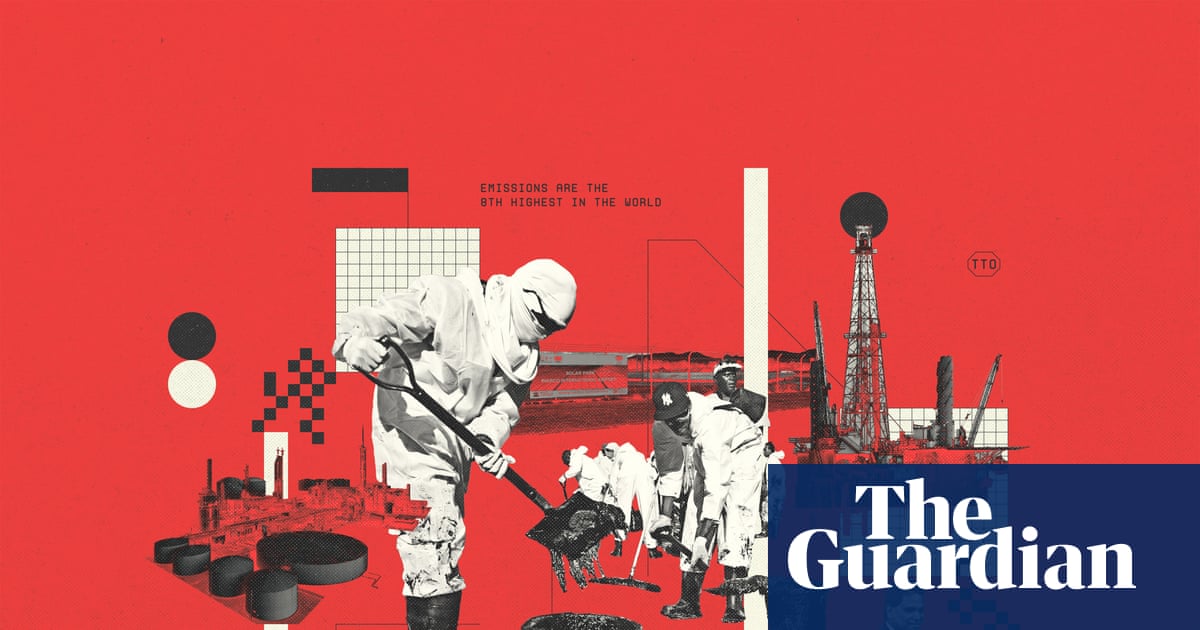

The accusations come at a time when Noboa’s administration has been criticised for pushing ahead with mining projects that had been blocked by public consultations, and accused of doing nothing to implement the 2023 referendum decision to halt oil production in block 43 of the Yasuni national park, an area of the Amazon rainforest famed for its ecological diversity. Instead, the president has subsumed the environment ministry inside the mining ministry.

after newsletter promotion

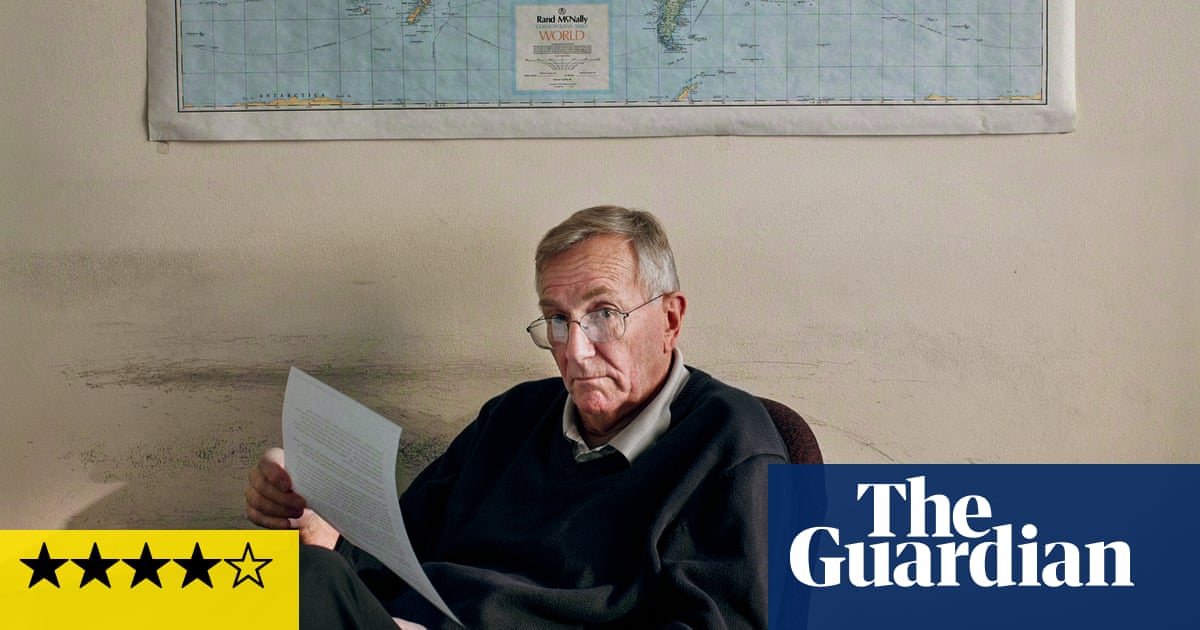

Alberto Acosta, who helped to draft the current constitution as a president of the last constituent assembly, said: “We have the only constitution in the world that recognises the rights of nature. All of this is being systematically trampled on by the government of President Daniel Noboa. The president does not want to respect the constitution or public consultation.”

Acosta sees this as part of a global trend, led by the US president, Donald Trump: “What is happening in the United States is encouraging many governments in Latin America, and in Ecuador in particular, to mobilise extractivist forces that are destroying the ecological balance and affecting Indigenous communities.”

Justices fear the rule of law is under threat; in recent months, the constitutional court has been the only brake on presidential power, successfully delaying several of Noboa’s moves to remove civil liberties or environmental protections. When the justices suspended security legislation in August, Noboa denounced them as “enemies of the people” and organised protests outside the court.

In the past decade, Ecuador’s highest court has also set a global example in its rulings in favour of the rights of nature, most famously in 2021 when it declared mining permits in the Los Cedros cloud forest were unconstitutional because they threatened the biodiversity of a protected forest.

The retired constitutional court judge Agustín Grijalva, who played a key role in the Los Cedros ruling, said his former colleagues were under intense pressure, which could get worse depending on the referendum outcome. “They want to reform or replace the constitution so they can impeach constitutional judges,” he said. “They will have their own court. And that is very dangerous for democracy and also for nature. It would put at risk all of the rulings of the past.”

.png) 1 month ago

47

1 month ago

47