It’s a significant chapter of wartime history that has until now been largely confined to memory, private archive and songs by 1940s Trinidadian calypsonian Lord Invader.

Now, the hidden story of how Caribbean workers helped win the second world war has finally been revealed by researchers commissioned to make a film by Imperial War Museums (IWM).

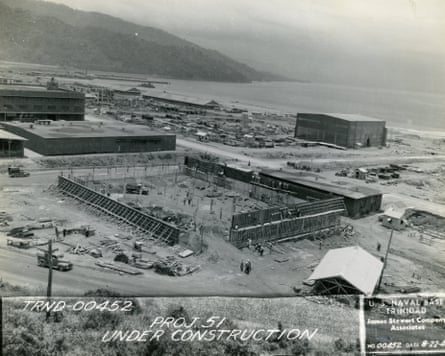

Labourers from across the British West Indies were recruited to build bases in the western Atlantic and Caribbean for the US, on what was then British territory.

It was a deal which changed history. It marked the emergence of the US as an interventionist global superpower, cemented the UK-US “special relationship” and prevented countries close to the US falling under Hitler’s control, securing victory in the Atlantic and freeing up forces and resources to defend Europe. It fired up independence movements in the Caribbean, while influencing West Indian music and fashion.

But the Caribbean civilians who built and worked on the bases received little recognition in the UK.

Now a new short film, Cornwallis Cloth, will begin screening at the Old Royal Naval College in London from Saturday, with a cast including Paterson Joseph (Peep Show, Noughts + Crosses, the RSC) and Suzette Llewellyn (Mr Loverman, Holby City) bringing the era to life. The film will be accompanied by an exhibition exploring its themes and the historical background of the stories it uncovers.

The installation follows 30 years of investigative research, including testimonies and diaries from Caribbean elders, veterans in the East End, merchant seamen, American airmen and German U-boat crew, co-director Tony Thompson said.

The Old Royal Naval College said they were “delighted” to present the film, while an IWM 14-18 NOW Legacy Fund spokesperson said the project “explores the transformational impact of war on men, women and children living in the British Caribbean, providing a new way to interpret and remember these important – if underexplored – stories.”

Thompson, who produced the film with Rebecca Goldstone, co-founder of Sweet Patootee Arts, said: “Thousands of workers from across the Caribbean were recruited to build all these air and naval bases in record time. They went wherever they were needed – Bermuda, St Lucia, Antigua, Trinidad – and did the heavy lifting and groundworks, putting up hangars and a lot of the outbuildings and laying roads.”

In the 1930s, Caribbean trade unions and workers were at the vanguard of the civil rights movement, with sugar estates, banana plantations, docks and coaling stations rocked by strikes and marches. Nonetheless, the British government resisted demands for universal adult suffrage and independence for Caribbean nations.

Soon after, however, the Atlantic became a theatre of war. As German U-boat submarine campaigns targeted shipping routes used for vital goods such as oil (from Venezuela) and bauxite, the raw material for aluminium, (from what was then British Guiana), the Caribbean became strategically important.

Britain was dependent on imports to survive and win the war. By 1940, prime minster Winston Churchill desperately needed new warships for the Royal Navy’s battle of the Atlantic.

The result was what has become known as the “destroyers for bases” deal, in which US president Franklin D Roosevelt agreed to provide US-built destroyer warships in exchange for bases in British territories in the Caribbean.

The air and naval bases – in Antigua, the Bahamas, the former British Guiana, Barbados, Bermuda, Jamaica, St Lucia and Trinidad – would prove critical to anti-submarine warfare.

For the workers of the Caribbean who volunteered to build them, it meant higher wages and political leverage.

Thompson, artistic director of Sweet Patootee Arts, said: “The only way the colonial powers could make those bases operational was to agree to civil rights concessions. Suddenly the British government and the colonial machine desperately needed the people whose resistance it had put down.”

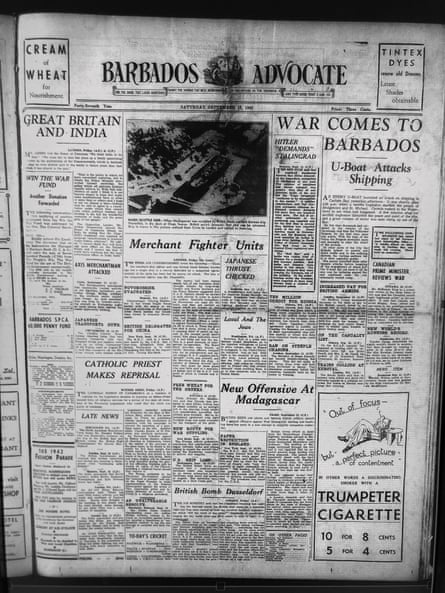

Cornwallis Cloth, commissioned by the Imperial War Museum’s Legacy Fund, explores Caribbean civil rights struggles in the war era through the story of the character Bonita Skeete, revisiting the 1942 German torpedo attack on the merchant ship SS Cornwallis in Barbados.

The story was inspired by oral histories that came from Barbadian elders including Belfield DaCosta Ifill, who travelled to Trinidad for construction work, and James Stewart, who went on to join the Royal Engineers after building military roads.

The film-makers also interviewed Michael Manley, the lawyer and trade unionist who became Jamaican prime minister in the 1970s, and Alfred Hilaire from Trinidad, who as a teenager was recruited to blast rocks, drive Jeeps and tie metal piles underwater because of his free-diving skills.

In Hamburg, the film-makers tracked down Herbert Schlipper, a former first officer on a German U-boat, who described how “everybody was happy” to be posted to the Caribbean after the “most terrible” fighting in the north Atlantic.

However, the allied anti-submarine warfare, supported by the chain of destroyer bases in the Caribbean, drove Axis forces from the region.

Songs recorded by Lord Invader in the 1940s, like Rum And Coca-Cola and Yankee Dollar – in which he sang “now the war is over, Trinidad is getting harder” – explored the impact of the US presence in Trinidad. But much of the era has been shrouded by “archival silence around Black history, cold war aspects and geopolitical rivalries”, Thompson said.

He added: “People just didn’t tell their stories. Some of them went on to join the RAF, others went back to plantations or came to the UK. There were Barbadians and Trinidadians who didn’t speak of this period for years.

“The American presence would have a massive impact on the Caribbean – the economy, the cultural and social experience. The influence can be heard in calypso and seen in the fashions of the Empire Windrush.

“It transformed Caribbean societies crippled by the Great Depression, plantation economies defined by squeezed wages and deliberate unemployment, all of which had fired up the civil rights movement. The tacit agreement between Caribbean workers’ leaders and colonial officials to support the war effort brought a semblance of equality.”

.png) 1 month ago

45

1 month ago

45