Katherine Moar’s riveting drama is inspired by the American heiress Patty Hearst who served a prison sentence for a bank robbery organised by a radical leftwing guerrilla group, the Symbionese Liberation Army. She had been abducted by the group months earlier and her court testimony told of how she was locked in a closet and raped during captivity.

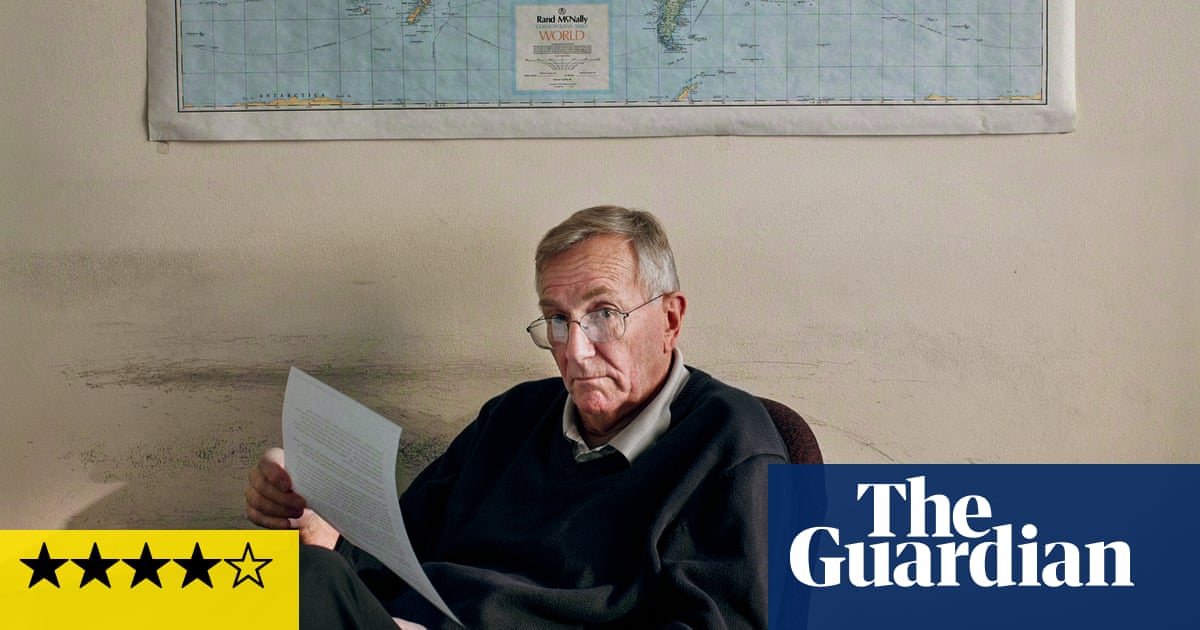

This memory play traces the fallout of such a case through a fictional encounter between heiress Holly (Abigail Cruttenden) and the attorney Robert (Nathaniel Parker) who lost her case.

They meet many decades after the event. Robert has become a celebrity lawyer in California and his life has been upended by allegations of sexual misconduct. He invites Holly, now fully rehabilitated into high society, to his apartment in hope she might speak out on his behalf. The ironies could not be greater, given the doubt he cast back in 1978 over her account of rape. “How things change,” says Holly. “Forty years ago, it was sex. Now it’s rape.”

It begins in 2017, a few months before the allegations of sexual assault made against Harvey Weinstein, though this is not spelled out. The toxic inheritance of the 1970s is revisited from our post #MeToo perspective. The subject matter is explored with gripping tension, although some of the complexities of Hearst’s case are flattened; there is no discussion of coercion or brainwashing, as there was around her trial. But all the issues are there, and the drama too, in abundance.

At heart this is a two-hander played out as a four-hander, with younger versions of both characters (Katie Matsell as the heiress and Ben Lamb as the lawyer) enacting flashbacks. Under the artful direction of Josh Seymour, the older characters turn to their younger selves and begin interacting with them, as if the past has turned to flesh and blood. It gives the play an audacious theatricality which works with surprising subtlety.

Neither Holly nor Robert are particularly likable: he is simply odious, she is self-regarding and entitled. But her privilege is part of the genius of this play: it still renders her powerless, despite her powerful family.

The play is best in combative mode and does not quite know how to finish but that doesn’t matter. Moar’s dialogue is so deft and sparkling, you could listen on and on. Her debut play, Farm Hall, about Germany’s nuclear programme in 1945, premiered at this theatre and found greater life in a West End transfer. This deserves to do the same.

.png) 1 month ago

48

1 month ago

48