Any Lucia López Belloza had not seen her parents and two little sisters since starting her first semester at Babson College, near Boston in August. A family friend gave her plane tickets so she could fly home to Austin and surprise them for Thanksgiving.

The 19-year-old business student was already at the boarding gate at Boston airport when she was told there was an “error” with her boarding pass; when she reached customer service, she was handcuffed and arrested by what she believed were two Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents.

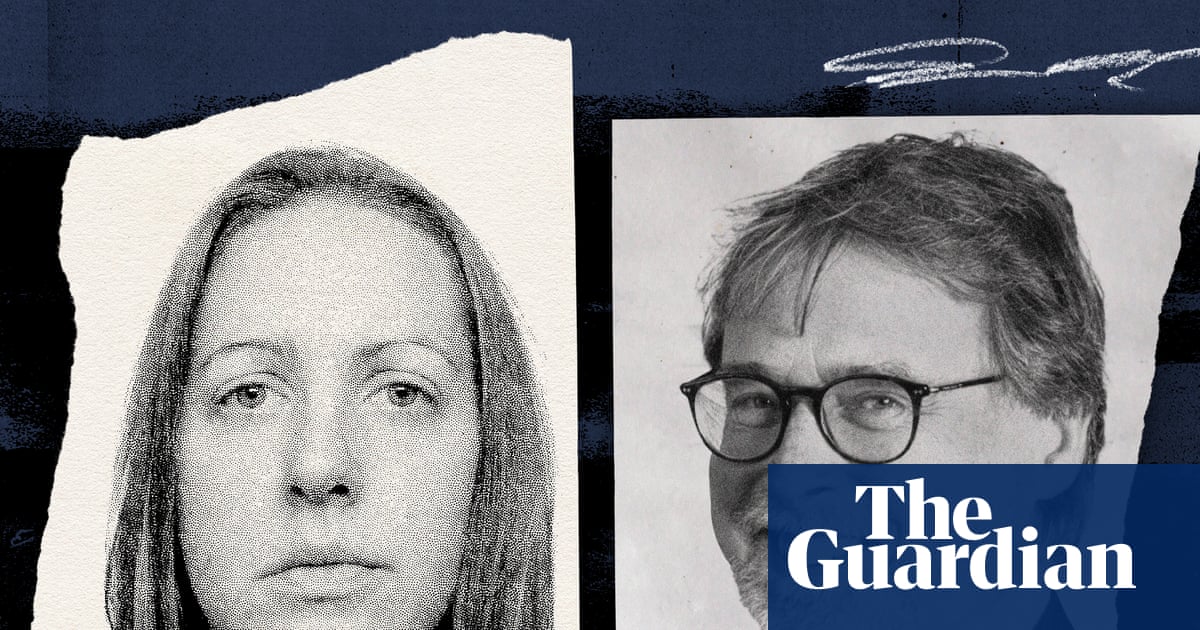

“I thought: ‘I was travelling to surprise my parents for Thanksgiving, and now the surprise will be that I won’t be there,’” López told the Guardian.

She was allowed a phone call to her parents, who contacted a lawyer. The next day, a federal judge issued an emergency order barring her removal from the US for at least 72 hours until her case could be reviewed.

But the next morning, she was shackled at her wrists, ankles and waist and deported to her native Honduras, a country which she left at the age of seven and of which she has virtually no memory.

Home to about 11 million people, Honduras is one of the main trafficking routes for drugs moved from South America to Mexico, and has spent decades grappling with the growing power of armed gangs that control entire neighbourhoods, extort families and recruit young people. The country’s homicide rate is three times the global average.

Honduras is also in a political maelstrom, with a knife-edge presidential election of which the vote count was has dragged on since Sunday, with local politicians and analysts criticising repeated attempts by the US president, Donald Trump, to influence Hondurans’ votes.

“I never thought I would go through this tragedy,” said López, who, since being deported on 22 November, has been staying at her grandparents’ home in San Pedro Sula, Honduras’s second-largest city.

Her lightning-fast deportation – less than 48 hours after she was arrested at the airport – has drawn global attention as one of the starkest examples of alleged abuses under Trump’s mass deportation policy.

“Her case is an unconstitutional horror show,” said her lawyer, the Boston-based Todd Pomerleau, who has represented other high-profile ICE detention cases, including that of the mother of the White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt’s nephew.

“She wasn’t told why she was detained,” said Pomerleau. “She was shackled like she was some type of hardened criminal, and then deported to Honduras with no opportunity to have a court hearing or even talk to an attorney,” he added.

“If that isn’t unconstitutional, I don’t know what is,” Pomerleau said.

Trump administration officials repeatedly said the chief focus of arrests and deportations was dangerous criminals, but – like most immigrants detained by Ice agents – López had no criminal record. Being undocumented in the US is not a crime but a civil infraction.

A Department of Homeland Security (DHS) spokesperson said López, “an illegal alien”, was arrested because she “entered the country in 2014 and an immigration judge ordered her removed from the country in 2015, over 10 years ago. She has illegally stayed in the country since.”

Her lawyer said that neither she nor he was ever shown the removal order, and that even if it does exist, a federal law stipulates that arrests in such cases can only take place within a 90-day window after the order is issued – “not 10 years later,” said Pomerleau.

“Her mum brought her here because of how horrific the circumstances were in Honduras, where gang members were killing and extorting people … They came here just like the Pilgrims 400 years ago, for a better life and to escape persecution,” said the lawyer.

Honduras “has a large out-migration problem”, said Elizabeth G Kennedy, a social scientist and Soros justice fellow who researches deportees in Central America. In the past decade, about a fifth of Hondurans left the country, most heading to the US.

In 2014, when López’s family left Honduras, their home town, San Pedro Sula, was considered the murder capital of the world and their neighbourhood, La Pradera, was one of the most violent.

“The children and families that I’ve interviewed from there [La Pradera] reported a very strong presence of gangs who forced multiple families to leave,” said Kennedy.

Gang violence takes a particularly heavy toll on women, having been the main driver of femicides in Honduras last year. Teenage girls are particularly affected, making up the majority of female victims of sexual violence.

“And now you have a young woman back in a country where it’s very dangerous to be a young woman, who was given no due process rights in the US,” she added.

Pomerleau, the student’s lawyer, said they are now awaiting an official explanation from the US government to the court as to why the emergency order barring her removal was not respected.

“It’s possible the government will say, ‘Sorry, we made a mistake here, and we’re going to bring her back’. That would be the easy and reasonable thing to do.

“But they might have a different approach, and that’s going to require me to make a forceful argument that the court order was violated and demand a remedy,” he said.

“We’re not stopping until we get her back”.

López said she was trying to keep her mind occupied: “I try to be as positive and as strong as I can”.

“I want to be able to move forward and maybe continue my studies, whether here [in Honduras] or by finishing my semester at the university. And one day, to be able to see my parents and my family again,” she said.

Babson College, the university she was attending in Wellesley, 14 miles from Boston, issued a statement addressing her case and saying that “our focus remains on supporting the student and their family”.

“My main goal in the US was always to study,” said López. “What happened to me isn’t fair, because we went there to study and work hard, to move forward in pursuit of that American dream so many of us had.”

.png) 2 months ago

53

2 months ago

53