Bill Smart has never heard the word “solarpunk”. But the softly spoken 77-year-old lights up when given the definition from Wikipedia: a literary, artistic and social movement that envisions and works towards actualising a sustainable future interconnected with nature and community.

Solar refers not just to renewable energy but to an optimistic, anti-dystopian vision of the future. Punk is an allusion to its countercultural, do-it-yourself ethic.

“That’s us!” says Smart, a retired mechanical engineer. “I never knew there was a word for it. I guess I’ve been a punk all along.”

Smart is giving a tour of his 110-hectare (272 acres) eco community on Australia’s Gold Coast, right on the southern border between Queensland and New South Wales. This weekend, the residents will celebrate the 20th anniversary of its foundation, though no one is sure how many people live there today. The last census was taken in 2017 and Smart estimates about 500 people call the village home.

In the 13 years since he and his wife, Susan, moved in, Smart says all kinds of people have made their home here at one time or another. There are retirees like themselves, young families, movie stuntmen, journalists, children from wealthy families, Buddhist monks, composers and the odd recluse looking for privacy.

“This is the way people should be living,” says Smart. “You know, you can live in a suburb and you don’t know your neighbours. People drive into their homes, lock the garage door. Here everyone knows each other. Everyone helps keep an eye on the kids.”

It takes all types to make a village, he says. Just about the only creatures not welcome in this one are cats and dogs. Currumbin Ecovillage was conceived as a wildlife sanctuary and corridor for native Australian animals. A cat or dog may be another member of the family but they are also hungry carnivores, lethal predators and territorial animals that have significant environmental and climate impacts. For a community built around meeting the needs of humans and nature, there was no room for feline and canine friends, even on a temporary visit. Smart says: “Dogs are nice and very loyal and everything. We do miss having a dog but that’s the price we’re prepared to pay.”

It is a rule the community has learned to be firm about – certified service animals excepted – especially among people visiting the cafe. There is no shortage of animal friends in the village, Smart says. It is built on the site of an old dairy farm – the milking shed is now a community centre and library – and a reforestation effort has brought back native wildlife. Mobs of wallabies and kangaroos wander the village at will. Frogs, snakes and birds also make it their home along with bandicoots, koalas, echidnas and platypuses. Some residents keep pigs, goats and chickens.

The village has imposed other constraints to help achieve a sustainable life. At first, new homes had to meet certain demands about orientation, design and the proportion of recycled materials. Each had to supply its own power and water with solar panels and rainwater tanks. The newest buildings do not always meet these standards because the original developer went bust in the 2008 financial crisis and its successors have had a different approach. However, the commitment to sustainable living is still strongly encouraged.

As an “intentional community”, Currumbin Ecovillage is a contemporary spin on an old idea. Rob Doolan, a town planner for 45 years, has worked with more than 120 such communities over his career. The idea for planned and collectively managed communities began with hippy communes that formed after the 1973 Aquarius festival in Nimbin, over the border in New South Wales. Some of those who came for the party stayed and found that pooling their limited resources together allowed them to buy large tracts of land by shared title.

Often these properties were struggling dairy farms where the rainforest had been cleared to leave a mostly barren landscape. The catch was that sharing title was illegal, which made getting a loan difficult. The sheer number trying this approach eventually led to legal, regulatory and financial change, paving the way for Currumbin and similar communities such as Jindibah, outside Byron Bay in New South Wales.

after newsletter promotion

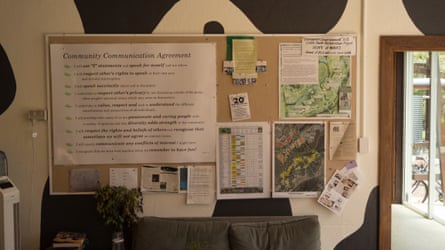

“Intentional communities can do things that people in normal suburban situations might not find easy or practical because they’re trying to do it on their own,” Doolan says. “The invisible bits are the important ingredients here. They have a management structure, a shared financial structure. Of course, there is the old joke that the biggest problem with intentional communities is they also involve dealing with other people.”

When it comes to decision making, personality clashes and relationship problems can come into play, but Smart says this is true of any human endeavour. Working together, Currumbin villagers replaced their A$2m (£1m) wastewater treatment plant, which allows for the re-use of water for non-consumption and ensures the village remains self-reliant. Down the track they may take on other projects including a solar farm and community batteries.

Everyone in Currumbin pitches in. Smart helps teach woodworking skills and runs three community garden spaces where all the produce goes to OzHarvest, a charity that helps unhoused people and others in need.

Every Friday, people head down to the cafe for happy hour, and when a new baby is born – there was a home birth a fortnight ago – the residents rally round to make the family’s meals for two weeks. These are the things that, Smart says, make it worth living here: “It’s not about the structures, it’s about the people.”

.png) 2 months ago

53

2 months ago

53