Ellie Kildunne says it’s not quite sunk in yet. A couple of months on from winning the Rugby Union World Cup with her England teammates, she’s still on a high. I ask if she slept with her winner’s medal by her bed the night they won. “That night?” She gives me a look. “It’s still by my bed. Every day. I wake up and the medal’s next to my bed. And it’s, like, as if!”

But Kildunne is not resting on her laurels. She says the medal is also a reminder of what’s left to achieve – for her, and for women’s rugby in general. “Your heart’s telling you that you’ve done it, but I need to refocus. So it’s about how can we win the prem, how can we win another Six Nations, more World Cups? How can we keep fans coming to games? We’ve sold out Twickenham, so how do we do it again?”

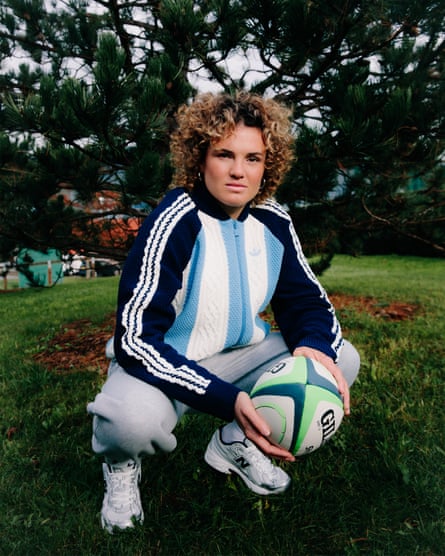

Kildunne is a freak, as she tells me time and again. First of all, there’s the way she plays the game. Rugby is a team sport involving strict discipline and complex rules. But Kildunne, a full-back, plays largely on instinct and is impossible to predict. She has phenomenal speed and stamina (an unusual combination), exceptional grace and strength, pops up anywhere on the pitch, and could out-sidestep Fred Astaire. In 2024, she was named World Rugby women’s 15s player of the year – the greatest individual honour in the game.

In September’s World Cup final against Canada, she scored a try that reminds me of Diego Maradona’s legendary goal for Argentina against England in 1986 (widely regarded as football’s greatest World Cup goal ever). Kildunne caught the ball on the left flank about 30 yards from Canada’s try line, she ran through two players, sprinted past a third, swerved past a fourth, then a fifth, raced past a sixth and seventh before planting the ball down in the middle of the goal. Genius.

One of the great sights of the World Cup was seeing Kildunne and her fellow England teammates Meg Jones and Jess Breach celebrate scoring with the cowboy dance – one hand on the hip, the other throwing imaginary lassos above their heads, while bobbing side to side on their imaginary horses. Joyous.

Kildunne scored another audacious try in the semi-final a week before, crossing the entire pitch as she swerved past player after player. She admits this try gave her an extra buzz because it came after a spat with the opposition. “Just before, I’d given one of the French girls a bit of chat, told her to shush – it got out on camera.” Does she often sledge the opposition? “I try not to, but the French woman pushed me and another one of the girls in the back. I’ve done it before, when I scored a try and a girl was getting in my ear. Before I put the ball down, I waved at her. That caused a bit of havoc as well.” Do her opponents think she’s arrogant? “I’m sure people do, but I’m not big-headed.”

We meet in Guildford, Surrey, at the training ground of Harlequins, her club team. Her self-belief is obvious from the off. She’s a supreme athlete, and she knows it. But there’s more. She’s also a brand expert – the brand in question being Ellie Kildunne. To be fair, she is a hugely marketable asset – brilliant, good fun, eloquent and thoroughly eccentric. Ask her to describe herself, and she does so in one word: chaos.

One of the unusual things about Kildunne is that both she and her younger brother Sam play rugby (he is a winger for Ampthill club and has played for England rugby sevens) despite coming from a non-rugby household. She grew up in a remote farmhouse in West Yorkshire, but there were families with kids on either side, so she played football with the boys from an early age. Kildunne is a Liverpool fan, and she adored Steven Gerrard and Fernando Torres. One day, she was playing outside with her neighbours and they were called in because they had to go to rugby training. If they were doing rugby, Kildunne reasoned, why shouldn’t she? And that’s how it all started. As with football, she was the only girl on a boys’ team. Did she feel weird? “I didn’t think about it, because it was my normal. I just thought it was weird that other girls didn’t play, because I knew how much I enjoyed it. I knew I was different. And I don’t think that’s a bad feeling. It’s cool to be different.”

Has she always had that confidence? “Yes. I was talking to someone about it the other day. I remember having this thing in my head when people asked me why I played rugby. I must have been 11 at the time, and I said, ‘If you go to a farmers’ market and there are loads of green apples, but in the middle there’s a red apple, which apple do you think about the most? You think about the red apple. I’m that red apple.’ I’ve always been that red apple. I’m not a sheep.”

Kildunne, aged 26, says her childhood was idyllic. Her mother (who works in marketing) and her father (who trains sales people) encouraged her and Sam to do whatever they wanted. Their home was so remote they weren’t in a school catchment area, so her parents made sacrifices and educated the children privately. Did her school have great sports facilities? “Yeah, but I don’t think that made me what I am today, because private schools are very traditional. I was told to play netball not rugby, and I wiggled my way in by getting my old rugby coach to come in and say, ‘Give her a chance.’” She was allowed to play in the B team with the boys.

At school, she was well behaved (not a single detention), academic (all A*s and As in her GCSEs), but still chaos. If she wasn’t forgetting things, she was losing them, whether it was her gum shield or boots for rugby or her planner for work. Her weekends were dedicated to sport – rugby league Saturday morning, rugby union Saturday afternoon, football Sunday. “I played as much sport as I could, for as long as I could.”

Were she and Sam competitive? “Incredibly. Over everything. We were so close, but we were really competitive. We still are, but it’s a lot more collaborative now. He watches my games and I watch his, and we talk about stuff in the most honest way – like, ‘That pass was shit!’” Nice, I say. She laughs. “But when you get a compliment you know it’s meant.”

Kildunne began playing rugby league for Keighley Albion and rugby union for Keighley, then moved on to West Park Leeds and Castleford. Kildunne was so single-minded she didn’t even consider that her parents might object when, aged 16, she told them she wanted to leave Yorkshire for Gloucester so she could join the semi-professional women’s rugby club Gloucester-Hartpury. Her parents weren’t happy and, for the first time in her life, they told her no. But she wasn’t going to be deterred. After much talk, and the shedding of many tears, they conceded. Two years later, in autumn 2017, she made her England debut as a substitute against Canada. Of course, she scored a try. And it’s gone on like that ever since. She has played 57 times for England scoring 235 points.

I admit to her I know sod all about rugby. She seems delighted. “I love that. That’s cool. I don’t like it when journalists know all about rugby, because they just ask me the rugby questions you can search on Wikipedia, whereas I want people to know Ellie, not Ellie Kildunne the rugby player.” I reckon I’m not the only rugby ignoramus who’s a fan of hers. At the World Cup she made a splash, not just with the brio and audacity of her play, but with her cascade of corkscrew curls, big grin (few people smile as they’re playing any sport, let alone rugby) and, of course, the cowboy dance.

Where does the dance come from? “Me and Meg. Nobody knows this part of the story. We went on holiday with a few of the girls to Zante [also known as Zakynthos] a few years ago, just before Covid, and we had quad bikes. And we were, like, should we just be cowboys? Go and eat doughnuts and stuff. We were just being silly, like jumping off walls into the pool. Then when Meg came back into the Red Roses, we were in New Zealand [for the 2021 World Cup, which took place in 2022 due to Covid] and a bit bored on this day off, and there were scooters, and we were, like … should we play cowboys?” So what does it mean to be a cowboy? “Have fun!”

Do you have to be hard to play rugby? “It depends what position you play, but you’ve got to be pretty hard. The biggest thing is mentally you’ve got to be tough. I’m not going to be running into people. My job is to avoid people.” You still get whacked though, don’t you? “You do. People want to hit you. There are times when I question why the hell am I doing this?” Really? “Well, when it’s raining outside, and someone’s just stood on my hand, my toes are freezing and I’m running into someone who’s tackling me – you do think, why do I do this?” She stops, and smiles. But I never think I don’t want to do this. I wouldn’t do anything else for the world.”

What’s the worst injury she’s suffered? “Ach, I haven’t had major injuries,” she says dismissively. “I’ve broken my hand, torn my hamstring, torn my calf, had shoulder surgery. They’re not too bad, touch wood, but it’s all part of it.” I wonder what she considers a serious injury.

Kildunne is not built like a prop forward (rugby’s classic brick shithouse – think Joe Marler, as seen in Celebrity Traitors). But look at some of the photos of her on Instagram and you can see just how defined she is – six-pack, washboard stomach, ripped biceps. She says she was reluctant to muscle up in the early days. It simply wasn’t her idea of womanhood. “I remember being at school and everyone wanted to be a Hollister model – tiny runway models – and everyone wanted the thigh gap. I didn’t want to put on loads of muscle mass because I was young and impressionable, and you see what you see on social media.” But Kildunne came to understand her lack of strength was holding her back. “I got a stress fracture in my knee because I wasn’t strong enough. So I realised I needed to knuckle down and get stronger and more robust. I had to flick a switch and learn to enjoy the gym; enjoy being strong.” And she does now.

Thankfully, she says, the Hollister ideal is changing. Kildunne points out that the more there are visible, successful women in sports such as rugby, bodybuilding and weightlifting, the greater the variety of role models for girls and young women. “Now there are so many women of different sizes and with muscles, and they’re prepared to show them off on their personal Instagrams. So, where it used to be the tiny, slight women on magazine covers, now you’ve got people like Ilona Maher, the American rugby player, who is a superstar and incredibly strong. Now, the younger generation has Ellie Kildunne to look up to.” For a second, I assume she’s talking about somebody else. But I soon discover she often talks about herself in the third person.

“I’m proud of my body. My body is what’s made me an Olympian and a world champion. I’ve got muscles on my arms and shoulders when I’m wearing a dress and I’ve got strong legs. I do have a bit of tone on my tummy. And all this helps make me a good rugby player, and keeps me on the pitch.”

Even when she started playing rugby for Gloucester-Hartpury, she didn’t really believe she could make a career of it. The ticket sales and salaries still fall far short of the elite men’s game, which, in turn, falls far short of elite football. A couple of years ago, Kildunne said top-ranked British players, such as herself, made £40,000-£50,000 a year from the game. She wasn’t talking about a salary; that was a combination of club wages, fees for playing international matches and the few advertising/marketing opportunities that existed. And even this would have been unimaginable a few years ago.

after newsletter promotion

What about now? “It’s way better than what it was then. I think it’s against my contract to say what I’m on, but you get your England salary, which was upped just before the World Cup, your Quins salary, your PWR (Premiership Women’s Rugby) salary, and then your commercial brands. We’ve gone from doing free appearances to signing deals with brands. It’s a nightmare for mortgages, because we get paid in all these different formats.”

But, she says, it’s about so much more than the money. Kildunne has often said it’s easy to have great moments in sport, but she wants to be part of something bigger, something more significant. She is determined to be in the vanguard of a movement revolutionising women’s sport. And she’s convinced that this is finally happening.

The Red Roses have won the World Cup twice before this year (1994 and 2014), but women’s rugby was smaller then. “This is the golden age of women’s sport. I truly believe that. It’s not just what the Red Roses have achieved, but what British women have achieved in general in sport over the past couple of years is going to shape the future for the next generation.”

Kildunne says the Lionesses led the way by winning football’s Euros in 2022. Back then, she was invited as a guest to the Sports Personality of the Year ceremony (Spoty), and she couldn’t believe it when England women’s football captain Leah Williamson knew who she was. For all that self-assurance, she still didn’t expect anyone to recognise her, let alone fete her. When a fan asked for a selfie at a match a few years ago, she thought she was being asked to take the fan’s photo, which she did. The fan had to explain that she wanted Kildunne in the frame.

How times have changed. Now, she’s expected to be on the shortlist for this year’s Spoty and she gets stopped regularly. But it still surprises her. “I was in the petrol station the other day and a policeman tapped me on the back, and I was, like, ‘I’ve done nothing wrong, officer.’ And he said, ‘You’re Ellie Kildunne, aren’t you? I just want to say congratulations.’ I said, ‘God, I thought you were going to take me away and lock me up.’ I thought, that’s crazy – you know who I am, and you’re inspired by what we’ve achieved.”

A while ago, Kildunne’s boyfriend, a businessman called Cameron Sommerville-Bailey, said he cleaned her boots for her because “you can’t expect the world’s best player to clean her own”. Sommerville-Bailey used to feature regularly in her social media, but has been absent recently. Are they still together? “No. We split just before the Six Nations. It was very amicable. We lived together for four-five years. I still love him to pieces, but it was the best for where we are. I couldn’t have asked for someone better, right down to washing my boots. It was his love language!” Is there a new boot cleaner on the scene? “No, there is not.” She says she doesn’t have much time to think about her love life at the moment. There is so much going on – the rugby, a podcast series, loads of promotional work.

What’s her life like away from rugby? “Chaos,” she says instantly. In what way? Well, she says, she lives her life the way she plays her rugby: nobody can predict what she’ll do next. She can’t keep still, she has to keep moving, and she has endless micro-obsessions that come and go. “I got diagnosed with ADHD last year, which was really good for my understanding of why I can be fine with the way my life is, but when I explain it to someone else, it blows their mind.”

What does she mean? “I’ll go to bed and I can’t go to sleep, because I’m thinking I want to change my room around and I can see what it looks like in my head. So I have to get up and do it. Then I got a huge canvas, and I was in bed and I couldn’t stop thinking about painting it, so I had to get up and paint it through the night.”

Then there’s her thing with music. “I wanted to learn how to play a song on guitar. And, again, I couldn’t go to sleep because I’m thinking about this God-damned guitar. So I bought two guitars. I painted one of them because I thought it would be cool as a canvas. It looks rubbish. And the other one I bought so I could play this song on it.” Can she play the guitar? “No!” That’s the point, she says. That’s the chaos. “Then I got a keyboard because I heard a song and decided I wanted to learn how to do that on the keyboard.” Can she play the keyboard? “No!” she says. “I couldn’t learn it in a day. I spent the whole day trying. Did not move from that seat.” She’s also got a drum kit in her garage. Can she play that? “No. No!”

Then there’s her main obsession: photography. She’s actually pretty good, she says. She still likes to turn up to events with a camera round her neck, so people think she’s the official photographer. It makes it easier to mix with people, she says. They ask her to take a photo of them, she obliges and it’s an icebreaker. “There are cameras all over my house. I love cameras.” How many? “Well, professional cameras, I’ve probably got four. Then I’ve got two different vlog cameras and a couple of digital cameras. That’s my switch-off; when I’m at rugby, I’m so focused on rugby.”

And finally, there’s her penchant for DIY tattoos. “I just randomly bought a tattoo gun off Amazon. Who does that? Well, I do.” How much did it cost? “£30.” She shows me a dot on her finger. “That represents my brother.” And two dots on another finger. “That’s my mum and dad.” To be honest, as tattoos go, they’re rubbish. Then there’s the tattoo on her leg. “I tattooed myself on my ankle, but it was shit.” She corrects herself. “It is shit. It’s meant to be a heart.” But she’s not letting a lack of talent hold her back. “I’ve tattooed a few of the Red Roses and a few of the GB sevens girls. My most recent one was John Mitchell, our head coach. I did him after the World Cup. His first-ever tattoo, and if you know Mitch, he’s a bit of a hard nut. Everyone was like, ‘You gave him a tattoo? As if!’ And I was, like, ‘Yeah, I did.’”

I’m getting exhausted just listening to all her activities. Does she drive herself mad? “All the time. But I drive myself mad when I’ve got nothing on. I know I need to calm down. My mum and dad say to me, ‘Just calm down, don’t be on your phone, don’t be thinking about the next thing, project, idea, just relax.’”

But she thinks her inability to sit still is also what makes her a great sportswoman. Whatever she turns her attention to – painting, photography, tattooing or rugby – her focus is absolute. The only difference is that when it comes to rugby, she’s a world-beater. She spends lots of her spare time watching videos of rivals and teammates playing, studying their every physical move and mental reaction. “I hyper-focus on how quickly can this person in my own team catch the ball then pass it, and I watch it over and over again so I know how to time my run. Before a match, I’m, like, ‘OK, what does this woman do? She steps off her right foot about 70% of the time, left foot 30%. What’s her mental state? Does she lose her head easily? How can I get into that, without being an arsehole?’ I think about all those things.”

You really are a freak, I say. She grins. “I am. It makes me the player I am. I’m not the player who’ll do ice baths, who’ll eat fish and a rice cake every night, and wake up at 5am and do my stretches. That type of stuff doesn’t bother me. But I put in so much work that people don’t see. John always says I’m a freak. We do a 1,200m test and I smash everyone at that. No one gets near me, but I’m also the fastest. Normally, sprinters are not very good at the 1,200m. I’m good at both, so he says I’m a freak of nature. I take it as a positive.”

Kildunne’s late for training, so she has to leave. As she heads off, she reminds me that this is just the start – for her, for her fellow Red Roses and for women’s sport. “I don’t see this World Cup as the pinnacle of our careers. We’ve got the ball rolling, and it will take us into places we’ve never been before.” She’s got so much ahead of her, she says. “I am a very optimistic person. I never want to be at the peak of my career. I just want to keep on going and going, till I can’t walk any more.”

.png) 2 months ago

70

2 months ago

70