“The security blanket is covering us, but maybe we have a foot out in the cold.” That was the typically colourful warning from the International Monetary Fund’s managing director Kristalina Georgieva this week to its gathering of finance ministers in Washington.

At its spring meetings in April, the IMF said the erratic trade policies emanating from the White House, half a mile away from its glass and steel HQ, amounted to a “major negative shock”, for the global economy.

Since then, experts’ worst fears have not materialised – global growth has held up; frantic negotiations, agile manufacturers and new trading links have prevented supply chains collapsing.

But the US economy has been cushioned against the full effects of the trade shift by the AI mega-boom – and the IMF issued a clear warning this week that it may not last.

In its Global Financial Stability Report, published on Tuesday, the IMF said markets appeared “complacent”, given the policy tumult of the past few months.

It highlighted three reasons to be anxious: overstretched valuations for tech stocks; volatility in government bond markets as they absorb fast-growing debts; and risks in the burgeoning private credit sector.

Georgieva said it was this last worry, in particular, that exercises her. Since bank regulation was tightened in the wake of the catastrophic global financial crisis of 2008, other less heavily scrutinised non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), such as investment firms, have piled into the lending business.

The IMF frets that this huge “shadow bank” sector could unleash global chaos if loans start to go bad – particularly since many of the firms involved are funded via borrowing from mainstream banks.

“Adverse developments at these institutions – such as downgrades or falling collateral values – could significantly affect banks’ capital ratios,” it warned. In total, it found banks in the US and Europe have $4.5trn of exposure to NBFIs.

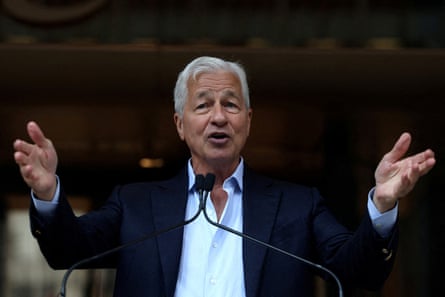

The recent collapse of the US car parts supplier First Brands, and the sub-prime auto lender Tricolor, which had relied heavily on complex private credit financing, were regarded by some market veterans – including JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon – as a sign that more problems may be in store. “I probably shouldn’t say this but when you see one cockroach, there’s probably more,” he told an analyst call this week.

Within days, market fears had turned to a pair of shaky regional banks – Western Alliance and Zions Bank – and the sell-off continued into Friday.

The Trump administration, not fans of financial regulation, appear relaxed about the issue, and more concerned with hammering China for its perceived unfair industrial and trade policies.

Washington is expected to use its chair status of the G20 group of countries next year to press for more international action to curb “imbalances,” such as Beijing’s persistent trade surpluses – with the IMF playing a role in policing member countries’ policies.

In DC this week, though, it was the risks of more “cockroaches” emerging from the vast and globally connected US financial system that were exercising policymakers: especially veterans of the global financial crisis in 2008.

Asked about the issue of private credit at her press conference on Thursday, Georgieva said: “We are asking the question, what should be done to have more oversight and a better view of what is happening there?” She added that the question “keeps me awake every so often at night”.

For Rachel Reeves, the whirl of meetings in the US capital was a welcome reminder that the UK is far from alone in facing pressures on tax and spend, skittish bond markets – and tariff chaos.

after newsletter promotion

The chancellor’s energetic Canadian counterpart, François-Philippe Champagne, with whom she has struck up a friendship, also has a tough budget to land next month, as Mark Carney’s administration comes to terms with a new harsher relationship with its neighbour to the south.

And such is the political instability in France – driven by financial pressures – that Reeves would have met her fifth French opposite number since Labour came to power last year, had Roland Lescure not stayed home to face the no confidence votes in his prime minister.

Reeves used the trip to start rolling the pitch for tax increases at next month’s budget – including on the wealthy – and was rewarded with sliding yields on UK government bonds, known as gilts. The yield, which moves in the opposite direction to prices, determines the interest rate the Treasury pays to borrow from investors.

Analysts said the gilt moves were also part of a “flight to safety” as markets fret about the credit sector; but Treasury strategists were gratified nevertheless.

Meanwhile, as if to underscore the IMF’s concerns about a “sudden, sharp correction” in markets, its global financial stability review was launched at a press conference on Tuesday morning to a background of plunging stock prices. The fall was driven by Donald Trump upping the ante with China, posting a warning on his Truth Social platform that the US could cut off – of all things – cooking oil imports in retaliation for Beijing not buying its soya beans. Wall Street later rallied to close up on the day.

Across town that same day the Bank of England governor, Andrew Bailey, was telling an audience of investors at the Institute for International Finance conference that “we have to watch very carefully just how stretched valuations are becoming”. With typical understatement, he added: “There are very different potential paths at the moment.”

As the IMF was careful to point out, any reversal in the AI boom would have real-world impacts, as tech firms backed away from the investment that is powering the construction of vast datacentres across the US and beyond – and driving a wave of tech imports from Asia. “The decline in aggregate investment could be rather sharp,” it warned.

And a crisis, if it came, would hit a politically fragmented global economy, in which many governments’ finances are already stretched – with debt on course to hit its highest level since the aftermath of the second world war.

The temperatures in DC were unseasonably chilly this week – but the IMF did its best to warn policymakers, preoccupied with domestic struggles, of the mounting risk the global backdrop could cool sharply in the months to come.

.png) 1 month ago

51

1 month ago

51