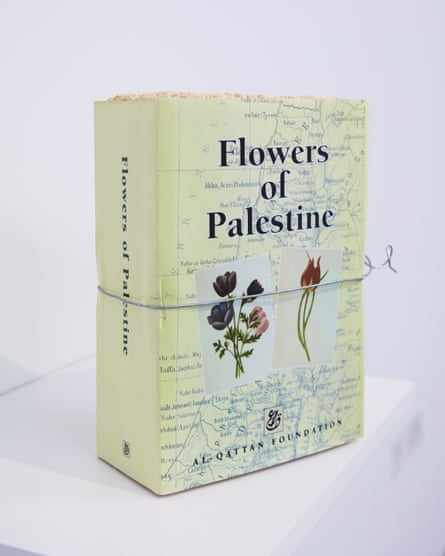

The work of Claire Fontaine is filled with rich and complex objects and images whose status and meaning is constantly in flux. There are jokes. There is a handwritten text in watercolour, copied out again and again, freeing the writer from the injustices of their ancestors (I AM FREE, it concludes). There is work riffing on Marcel Duchamp’s moustachioed and goateed Mona Lisa, swapping his ribald but puzzling 1919 caption LHOOQ with LGBTQ+. There are book jackets about Palestine’s wrecked ecology and visual activism in Palestine post 7 October, each wrapped around blocks of stone, like messages to be sent crashing through somebody’s window.

At the 2024 Venice Biennale, Claire Fontaine’s neon signs reading Foreigners Everywhere appeared and reappeared, written in dozens of languages, around the Giardini and the Arsenale, and also lent the biennale its overall title, turning a familiar kneejerk complaint into a celebration of difference. A new neon sign reading FATHERFUCKER, suspended and glowing behind the window of Mimosa House, opens their biggest London show to date.

Someone walks by and catches the word in their peripheral vision. Taking a couple of steps backwards, they rewind to look again. Others lark about at the window, taking selfies. Someone else has already alerted the council to complain. “The word motherfucker probably comes from a place of a total lack of empathy. We’re at the point where we don’t have any sympathy any more,” Fulvia Carnevale tells me, as she and James Thornhill, collectively known as Claire Fontaine, are finishing the installation of their show, called Show Less, in the gallery. Fatherfucker reverses the insult. “These works are all about injustice,” Carnevale adds. “The show revolves around structural injustice and how we deal with that. You know, patriarchy is an injustice, but it’s an injustice for men too.”

Claire Fontaine call themselves a “ready-made artist”, their name borrowed from the famous French stationery brand. Claire Fontaine also means clear fountain, which can also be taken as a reference to Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain, his ready-made urinal. Not all their references are so obvious. The gallery floors and stairs are completely covered in newspaper, filleted from recent editions of the Guardian, donated by the staff. This is a distant reference to a group of 1949 photographs by Robert Capa, showing Henri Matisse working on his designs for the chapel he was designing in Vence, outside Nice. Matisse had covered the floor of a temporary studio with newspaper, to protect the tiles beneath. Here, it is a news floor, a constant background rumble of yesterday’s news, cycling beneath our feet.

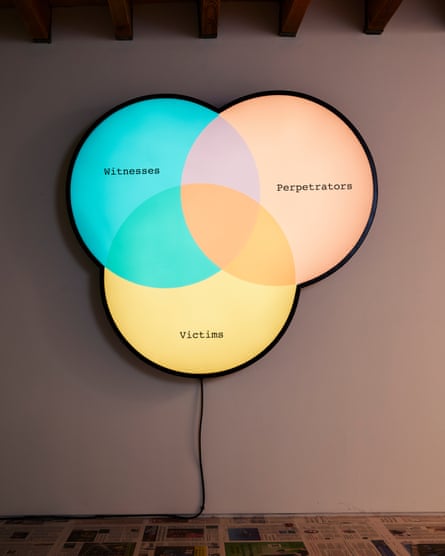

Currently, Thornhill and an assistant are mounting a big, backlit Venn diagram on the wall, three intersecting circles in blue, peach and yellow, the circles denoting witnesses, perpetrators and victims. Titled Intersections, Claire Fontaine sourced the diagram on the internet. It casts a blush of colour on the newspapers beneath. “It’s not about who’s innocent, who’s guilty, who’s the victim – it is about how do we deal with the violence of our daily life that is destroying every dignity, basically, for art, for making a symbolic action,” Carnevale says.

Two other light boxes, their proportions based on those of a mobile phone but vastly enlarged, like airport advertising, hang nearby. One contains a blown-up photo of a drawing smuggled out from a Yemeni prison and posted on the internet in 2018. Untitled (They Sexually Harass and Torture Then Photograph and Publish) is a sorry scrap of packaging foam on which a prisoner has urgently detailed their experience. The light boxes are overlain with a second image of a broken phone screen, the cracks becoming an integral part of the image beneath.

“This image is completely anonymous,” Thornhill says. “It is a description of the tortures that the prisoners were enduring.” Carnevale points at the crude little drawings. “This is somebody getting ready to be raped and these two guards beating this guy have been depicted headless. It’s an incredibly brutal image of total darkness and the scribbled Arabic text is a description of what you see. The fact that we’re seeing through a broken screen reflects in some ways the reality of how we don’t understand.” One part of the image was censored at source. We don’t know what has been blocked out. What you don’t see here is probably the most frightening thing about it.

Multiple lifesize copies of Gustave Courbet’s notorious 1866 oil painting L’Origine du Monde line one gallery: one closeup, spread-legged view after another of a woman’s pubis and vulva. Her breasts are partly swathed in a sheet. Having passed between multiple collectors, from an Ottoman diplomat who collected erotica to psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, Courbet’s painting is now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The copies, commissioned by Claire Fontaine, were all hand-painted in China, each one a subtly different transcription.

Previously, they had been working over postcards, including a Modigliani, Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe and his Olympia, each of them iconic paintings with naked women who are also staring at you. “We have vandalised them in a kind of feminist key,” says Carnevale. “We asked to get 12 copies made of the Courbet. Everything was done by hand, without resorting to copying over projections of the original. The slight changes in position, the hair, the sex, the vagina and the colour are all different. When they arrived at our studio in Palermo we felt like they were an accumulation of dead bodies. It started feeling like a rape scene. So then we worked on them slightly differently, less brutally, than in our postcard version.”

Sometimes, the spray painting leaves a mist or a bruise, a blush or a hint of gangrenous pallor. The spraying is horribly intimate. “You’re always kind of nervous about making the first mark, but then once you get into it, it decides itself. Painting is a kind of magical process,” says Thornhill.

after newsletter promotion

Is there a difference between painting and vandalising? “People who vandalise works in a museum are committing an extreme gesture of desperation and they pay with prison and everything, but we add value to these copies,” Thornhill suggests. “One way or another, the images are put in a state of extreme ambiguity, in relation to the original.” In any case, Courbet’s painting is still the subject of much academic debate. The postcard of Courbet’s painting is the second most popular in the Musée d’Orsay gift shop, after a Renoir.

We start looking down, scrutinising the floor and picking up headlines. What you have to watch out for is people who spend all their time in here looking at the newspaper instead of the other work. You seem to have a sort of an ever-expanding repertoire of works, that you use and reuse and recombine, I say. Your work is about reconfiguring.

“Foreigners Everywhere expanded in a way we never would have imagined,” says Carnevale. “Our work gets picked up and appropriated. Not worrying about being original frees you up. And it gives you a whole host of available material to work with.”

At one point, Carnevale quotes some lines from Bertolt Brecht, written in 1939:

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing

About the dark times.

It’s totally of our time, she says. “But now when you make songs about the dark times, they say you’re a sellout and a monster. In many moments, contemporary art has been a comfort to us in terms of being in a space where we are allowed to live and exist and do things that weren’t understood or valued elsewhere. Now, it looks like a space of privilege. And that’s bad for everybody. I think it’s about resonating with your present, and trying to keep a dignified position. People can say whatever they want, but I’m pretty sure that everybody needs to think that there is something out there that isn’t bullshit.”

.png) 1 month ago

43

1 month ago

43