Dana Schutz cakes her canvases in thick gobs of gooey paint. The American artist’s first proper London exhibition is a splodgy, orgiastic celebration of her material, but there are some big messages smuggled through if you can scratch your way towards them.

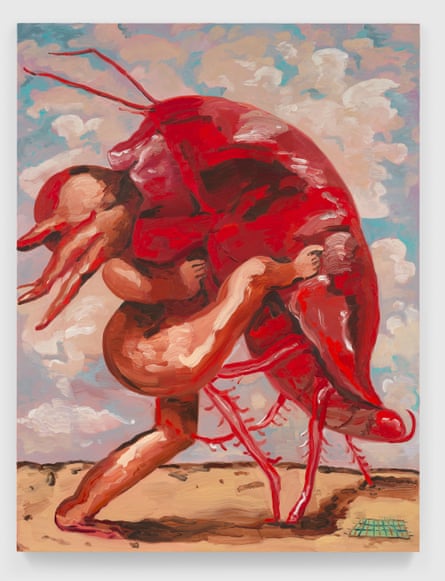

Schutz’s approach – which has seen her lauded as one of the most important figurative artists of her generation – is all about surface, brush strokes, colour and materiality. It’s painting for painters, real high-level art-nerd stuff. If you get your kicks losing yourself in layers of pigment and shadow, there’s enough here to keep you going for a while. But it’s Schutz’s grotesque, surreal, cartoony, metaphorical imagery that really makes the paintings tick.

The works in the first gallery are full of giant-headed cyclopses and baying crowds. In one, a group of figures stomps senselessly towards something off canvas, brandishing fists and leaving a trail of trash in their wake. In another, a figure is given a huge mask in some bizarre initiation ritual in front of a horde of ugly supporters. It’s not hard to read any of this as political, as commentary on the state of the US, on how society is divided and angry, and mob mentality is turning everything to rubbish.

In the other gallery space, Schutz seems to shift her focus to the people in power, rather than the crowds that follow them. Shadowy figures stuff their mouths with grapes and steak in a sombre dining room; a cardinal and a man in green recline in golden chairs – while in other works a couple console each other in a landscape filled with corpses, and a woman, maybe Schutz herself, lies naked, forlorn and powerless in bed.

This is ultradense, thickly layered stuff, covered in allusions. There’s the dreamy surreal symbolism of Odilon Redon, the fleshy pink cartoonishness of Philip Guston, the carnival grotesqueries of James Ensor, the big-headed weirdness of Paul McCarthy. There are riffs on the history of painting, countless nods to pop culture (I am almost 100% sure that one painting is a portrait of Handsome Squidward from SpongeBob SquarePants). You could spend hours spotting all the bits of Cézanne and David with which she’s littered the works.

Painting this dense, complex and allegorical leaves itself open to interpretation. I feel as if I’m being quizzed on the symbolism of a Titian but, for my money, there are two relatively clear narratives: the people in power, and the crowds that they bait.

And Schutz should know about that. Back in 2017, her painting Open Casket – a semi-abstracted depiction of the corpse of Emmett Till, a black teenager who was lynched by two white men in Mississippi in 1955 – caused untold controversy when it was shown at the Whitney Biennial in New York. She was accused of exploiting black death for her own gain. A protester picketed the painting daily, and others called for it to be destroyed. A white artist painting – arguably with great sympathy – a scene of black pain was the biggest story of the biennial. It was the peak of the late 2010s culture wars, a time that saw people turning on each other even if they were on the same side. Looking back now, in a world more divided, less nuanced and angrier than ever, it feels almost quaint that people had the time to get angry at this heartfelt, sorrowful painting.

It could have ruined her career, and Schutz probably wants to move on. But everything she’s done since exists in its shadow. She inevitably came out of that experience a changed artist. But what hasn’t changed is how good she is, how she still engages in brilliant, sickly, gloopy and deeply political painting at the highest level.

.png) 1 month ago

44

1 month ago

44