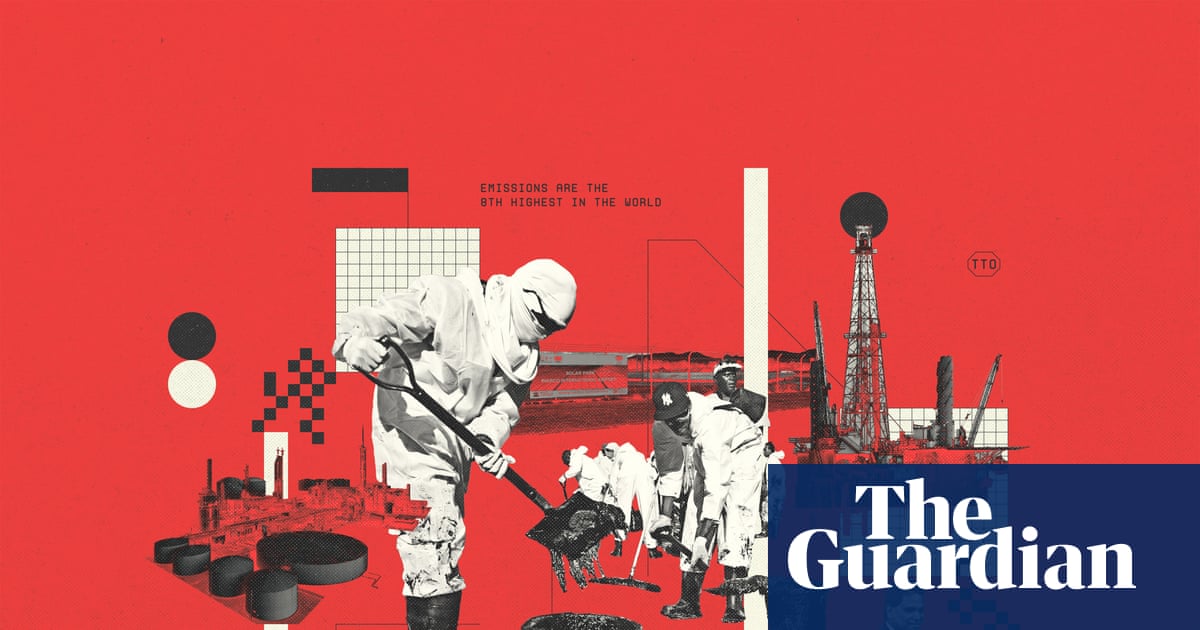

Councils in England will still be poorer by the end of this parliament than they were in 2010 despite Labour’s funding increases, according to analysis by the Institute for Government (IfG).

Funding cuts from 2010 to 2019 were so severe that they left gaps that could not be filled even by five years of above-inflation increases, leaving local authorities increasingly reliant on emergency funding and capable of only providing legally mandated services, the report shows.

The government increased local authority funding by more than 4% in real terms this year, and has promised an increase of more than 1% above inflation each year for the next three years. However, the IfG report suggests the damage done by years of cuts is so severe that many people will not notice any difference to their local services.

Stuart Hoddinott, the author of the report, said: “Most public services struggled when spending was cut during the early 2010s, but few as much as local government. Cuts were so deep that, even with sustained increases throughout the 2020s, funding is still due to be lower in real terms in 2028-29 than it was almost two decades earlier.”

Mark Franks, director of welfare at the Nuffield Foundation, which funded the report, said: “Over the past 15 years, per person spending on local authority services excluding social care has fallen by a staggering 38%. These cuts have had a direct impact on people’s lives, their wellbeing, and the resilience of their communities.”

The report tracked councils’ spending power since 2010, when the coalition government began to slash local authority funding. It found that even with Labour’s spending increases, English councils would have nearly 15% less spending power on average per capita than they did in 2010.

From 2009-10 to 2023-24, the researchers found, councils cut spending on youth centres by 60% and on libraries by 50%, and focused almost exclusively on essential services such as statutory social care, which now takes up more than two-thirds of budgets.

The rise in social care spending has been caused by an explosion in demand for statutory services for an ageing population, the rise in numbers of children and working-age adults with complex physical and emotional needs, and the ballooning cost of privately provided specialist care services such as children’s residential homes.

One interviewee told the report’s authors that local authorities had become “adult social care factories”.

The IfG also found a record number of councils were relying on emergency funding, and that if the government had not delayed a requirement for authorities to account for special educational needs provision, 40% would have been driven to the point of bankruptcy.

Hoddinott said that one reason for dissatisfaction with public services was that while money had started coming back into local areas, it was being almost entirely spent on essential services for vulnerable people, rather than amenities used by the general population.

Meanwhile, councils are increasingly using their budgets to pay for costly crisis services such as child protection and children’s homes, rather than preventive services. Spending on looked-after children went up by 71% between 2009-10 and 2023-24; over the same period, investment in early intervention services such as children’s centres fell by 79%.

These pressures are being most acutely felt in Birmingham, the country’s largest local authority, which declared itself effectively bankrupt two years ago and is still struggling to balance its budget.

The council’s latest figures show it is expected to use £80m of its reserve funds, about 8% of the total, by the end of the financial year, partly owing to a £13.4m overspend and £14m in costs from the city’s continuing bin strike.

.png) 1 month ago

42

1 month ago

42