“You speak about Miriam Makeba in South Africa and it’s like speaking about a queen,” says Alesandra Seutin. The legendary singer Makeba was known as Mama Africa, and the Empress of African Song; but she also hung out in Greenwich Village with Miles Davis and Duke Ellington. She was a teenager sent out to work to support her family in Johannesburg who later became a diplomat for Ghana, then Guinea’s official delegate to the UN. An outspoken anti-apartheid activist, she was the wife of a Black Panther. And her rich life and legacy are the inspiration for choreographer Seutin’s latest work, Mimi’s Shebeen, about to get its UK premiere.

Mimi’s Shebeen blends dance, live music and spoken word in a piece of theatre that’s no straightforward biodrama but draws on Makeba’s history, particularly her story of exile: after moving to New York in 1959 Makeba was barred from South Africa for 30 years because of her anti-apartheid stance. She was later banned from the US after marrying the Black Panther activist Stokely Carmichael. The show comes across like a ritual of remembrance, a deconstructed funeral – part eulogy, part celebration, part provocation – with the fabulous South African singer Tutu Puoane at the centre bringing Makeba’s songs to vibrant life.

In South Africa, a shebeen is an under-the-radar gathering place for home-brewed liquor and lively conversation, usually presided over by a shebeen queen. Makeba’s mother Christina was a shebeen queen who was arrested for illegally brewing alcohol when Makeba was 18 days old. Unable to pay the fine, Christina went to prison for six months, taking her baby with her, which is how Miriam’s eventful life began – just one of the things Seutin discovered when she began researching Makeba’s life. “So many stories!” says Seutin, when we meet at KVS theatre in Brussels after a performance of the show. Seutin’s father is Belgian and she mainly grew up there before moving to study and work in the UK, where she founded her company Vocab Dance. Her South African mother would sing Makeba’s songs, such as Pata Pata and Malaika, when Seutin was a child, and dance to them in the living room.

A decade ago, Seutin’s mother had cancer and was in hospital in London. “I stopped working for three months to take care of her and she was always requesting Miriam Makeba. She was so happy when we were singing together,” Seutin remembers. “I had so much time to kill at the hospital so I started researching.” As well as reading about Makeba’s triumphant return to South Africa in 1990, after the release of Nelson Mandela (whom she had met when he was a young lawyer in the 1950s), Seutin discovered that Makeba had been a breast cancer survivor in her teens, that Makeba’s daughter Bongi died in childbirth in 1985, and that because of her exile she hadn’t been able to attend her own mother’s funeral. “You see people and you look at their success and you forget that they are struggling like anyone else,” says Seutin.

All these thoughts went into the creation of the show (first staged in Brussels in 2023). Thankfully, Seutin’s mother’s treatment was successful, but the idea for the piece was to celebrate “death, life and mourning”. Within that, Seutin pulls out threads of Makeba’s biography like flashbacks, and nods more broadly to the theme of displacement and dispossession today. Although it’s not overt in the show, Seutin had in mind a second protagonist, a modern-day Miriam who is a migrant. “And we gather as these alter egos of characters connected to Miriam Makeba to welcome this young migrant.”

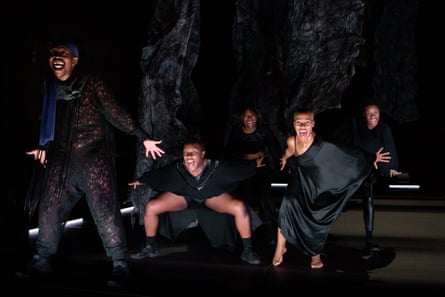

In the performance, rather than being intoxicated by the shebeen’s home-brew, the multi-talented dancers appear possessed by rhythm, in synthesis with the musicians on stage. Seutin’s choreography includes multiple styles of movement she has absorbed over the years, including from Rwanda, South Africa and Senegal (from 2020-24, she was co-artistic director of Senegal’s Ecole des Sables, the centre for traditional and contemporary African dance), plus the international cast’s own vocabularies, including street styles like krump.

Seutin was surprised to find that some of the younger, non-South Africans in the cast didn’t already know about the singer. (Makeba died in 2008 after having a heart attack on stage in Italy.) Why should younger generations learn about Mama Africa? “I think she would inspire young people to stand for what they are, speaking the truth,” says Seutin. “But she did it very gracefully. She’d say something poignant and then sing a beautiful song.” Seutin wanted to take the same approach in this work. “We see dancing and hear beautiful songs, an element of entertainment, but intertwined with strong messages and moments that hit. That’s what I admire about Miriam. Because if you are shouting too much, people won’t listen. They back away. But she did it in a way that you would receive it, and hear it, but still be graced by her talent.”

-

Mimi’s Shebeen is at Sadler’s Wells East, London, 22-24 October

-

Lyndsey Winship’s trip to Belgium was provided by Sadler’s Wells

.png) 1 month ago

52

1 month ago

52